Impact Of Emotional Disorders In The Functionality Of Children And Adolescents With Autism Spectrum Disorders Review

Marina Romero Gonzalez and Isabel P Valdivieso López

DOI10.4172/2472-1786.100012

1King's College London, London, Englando

2InfectiousUniversidad Técnica de Manabí, Portoviejo, Ecuador

- *Corresponding Author:

- Marina Romero Gonzalez

Fellow Alicia Koplowitz, Child & Adolescent

Psychiatry, Institute of Psychiatry

Psychology & Neuroscience, King's College

London, De Crespigny Park, London SE5 8AF, United Kingdom.

Tel: +44 (0)20 7836 5454

E-mail: marina.romero_gonzalez@kcl.ac.uk

Received Date: October 10, 2015; Accepted Date: December 07, 2015; Published Date: December 28, 2015

Citation: Gonzalez MR, López PIV, Impact Of Emotional Disorders In The Functionality Of Children And Adolescents With Autism Spectrum Disorders Review. J Child Dev Disord 2016, 2:4.doi: 10.4172/2472-1786.100012

Abstract

The main object of this review is to understand how emotional disorders develop and how they may interact with the score of functioning or with the severity of symptoms in autism spectrum disorder. We hypothesize that emotional disorders may influence negatively in the functionality of these patients.

This review was based on a systematic research of published articles available up to July 2014. The initial literature search resulted in 149 citations. Of those, 21 met the inclusion criteria. Many of the unselected studies from the initial pool involved samples outside the targeted age range (e.g., adults or pre-school children) or with non-ASD developmental disabilities. This review concluded that comorbid with emotional disorders among patients with ASD may be more common than previously thought. It may have consequent impairment in their psychological profile, social adjustment, adaptive functionality, cognitive and global functioning and should alert clinicians the importance of assessing mood disorders in order to choose the appropriate treatment.

Keywords

Autism spectrum disorder; Emotional disorder; Adolscents

Introduction

Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) is characterized by deficits in social interaction and communication, as well as the presence of stereotyped behaviour and restrictive interests [1]. In the past, all psychiatric issues in children and adults with autism used to be attributed to autism itself. However, an increasing number of studies are arguing about accepting behaviours and symptoms that had been considered additional or associated features of ASD as potential indicators of the presence of comorbidities warranting additional diagnosis.

An instinctive reaction is that comorbidity will generally lead to more severe impairments as a result of the cumulative effects of having more than one disorder [2]. Otherwise, the pathogenic courses that result in comorbidity may be overlapping, but nevertheless, unique. In the example of ASD, research has been delayed to some extent by nosological preconceptions about co-occurring symptomatology, many of which remain largely uncertain [3,4].

Autism is generally a lifelong condition beginning in childhood and with pathological outcomes in adulthood. Outcomes are often described as difficulties or issues in finance, employment and socialization [5-7]. Findings from these studies indicate substantial progress in the care and treatment of persons with ASD, allowing individuals to get more involved in community life with reduced burden on their families. Despite these advances, living with autism can be difficult [8], particularly during developmental transitions and critical periods of childhood. While all children with ASD exhibit one or more of the core domains (impairments in social interaction, communication and behavioural functioning), some children may have associated problems with mood and affect. Therefore, parenting for some children with ASD can be challenging and can severely impact family functioning as well as the health and wellbeing of caregivers and other family members [9,10]. Clearly, successful interventions for children with ASD have the potential to greatly affect health outcomes for the child and can have extensive economic benefits by contributing to the child’s independence when reaching adulthood.

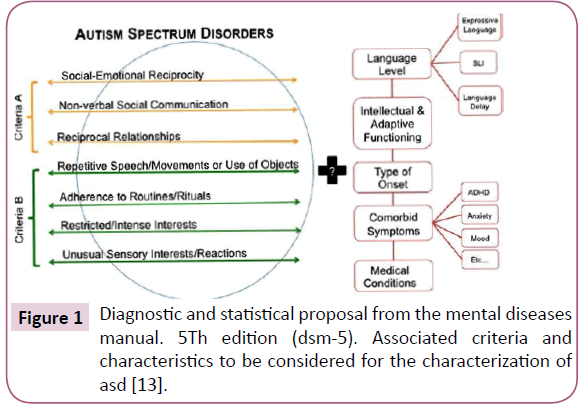

There is no doubt that comorbid condition can complicate the patient’s management. Reliable diagnosis of comorbid psychiatric disorders in children with ASD is of major importance. Emotional disorders are one of the main comorbid disorders often find in this population [11]. In this order, anxiety-related concerns are among the most common presenting problems for children and adolescent with ASD [12]. When other problematic symptoms are recognized as manifestation of a comorbid psychiatric disorders rather than just isolated symptoms, more specific treatment is possible. For this reason, one of the goals of the new DSM-5 classification must be to identify subgroups of ASD, including comorbid disorders and adaptive functioning, which may be important to understand the biological mechanisms, the clinical results and the reactions of the individuals with ASD [13] (Figure 1).

In the field of clinical research on ASD, we have well-established valid tools for the diagnosis of the spectrum disorder with Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised [ADI-R; [14]] and Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule [ADOS; [15]], but a limited repertoire of evidence-based tools for assessing change in day-to-day functioning.

In this paper, we focused on emotional disorders which include: anxiety disorders [including obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD) and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)] and mood disorders (bipolar affective disorder, depression and mania). We strongly believe that these pathologies can influence significantly in the prognosis across the social, familiar, adaptive, cognitive and global functioning of patients with ASD.

The main object of this review is to understand how emotional disorders develop and how they may interact with the score of functioning or with the severity of symptoms in ASD. We hypothesize that emotional disorders may influence negatively in the functionality of these patients. For all the reasons previously exposed, the specific aims of this review are: (1) to summarize the empirical research on the prevalence of emotional disorders in children and adolescent with ASD, (2) to provide which is the impact on the functionality or severity for this patients and (3) to offer future research that could provide better understanding in relation with the impact of emotional disorders in this population.

Methods

This review was based on a systematic research of published articles available up to July 2014. The Psych-Info and Medline online databases were searched using the following key words: (“autism” or “autistic disorder” or “asperger(s)”, or “pervasive developmental disorder”) AND (anxiety or anxious or mood disorders or bipolar affective disorder or depression or mania or obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD) or post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) or comorbidity AND functioning or functionality). Abstracts of identified articles were then screened for the following inclusion criteria (Table 1).

| •Inclusion Criteria (a) The target population included children or adolescents (between 6 and 18 years) diagnosed with an ASD including autism, Asperger's Disorder or PDD-NOS. (b) Prevalence of any emotional disorder (anxiety or anxious, mood disorders, bipolar affective disorder, depression, mania, OCD or PTSD) in this population. (c) Emotional disorders assessment with direct observation or report (from parent, teacher, or child) evaluations. (d) The association with score of functioning or any predictor of severity for the ASD. There were no restrictions on minimum sample size. All measures of functionality or autism severity symptoms were included. Exclusion Criteria * Unpublished dissertations or studies published more than 20 years ago. Secondary reviews were excluded, as well as studies not published in English. |

Table 1: Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

For brevity, the following abbreviations are used throughout this review: Autistic Disorder (AD), Asperger's Disorder/Syndrome (AS), Pervasive Developmental Disorder-Not Otherwise Specified (PDD-NOS), High-Functioning Autism (HFA), and Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD).

The initial literature search resulted in 149 citations. Of those, 21 met the inclusion criteria. Many of the unselected studies from the initial pool involved samples outside the targeted age range (e.g., adults or pre-school children) or with non-ASD developmental disabilities. The second phase, which systematically examined the three major autism journals, identified four additional articles. Because the purpose of the studies varied, they were classified into four broad categories according to their primary question in relation with the functionality: cognitive and executive functioning, social and family functioning assessment, global assessment of functioning or quality of life and other measure of autism severity symptoms. It should be noted that some of the studies addressed more than one domain. In this case, the studies were grouped and reviewed according to their primary research question.

Results

Cognitive and executive functioning

In this review, the authors focus on measures used in ASD clinical studies in order to evaluate the functionality (Table 2,2b). Out of the 25 studies, 6 of them focused their primary research question according with the cognitive and 2, with the executive functioning scores. Six studies reported information about the prevalence and the impact in the functioning being the main comorbidity the anxiety disorder [11,16-18]. The range of anxiety disorders was between 39,2 to 42,7 % [11,16]. All of these studies used different measures in order to assess the anxiety comorbidity and the ASD diagnosis. Weisbrot et al. [19] and Thede & Coolidge [20] used clinical evaluations which included interviews by child psychiatrists according to DSM-IV criteria. The rest of them [11,16-18] confirmed the diagnosis with at least one of the assessment criteria described on the Table 2,2b. Simonoff et al. [11] and Hollocks et al. [17] used the same sample of patients. As we can see on the Table 2 and according with the main results, Sukhodolsky et al. [16] and Weisbrot et al. [19] found a positive correlation; children with higher IQ were found to experience the most severe anxiety. On the other hand, Simonoff et al. [11] found that ASD diagnosis, IQ, and adaptive behavior were not associated with the presence of an anxiety disorder. Similarly, Pearson et al. [18] concluded that verbal IQ was not found to have any correlation with anxiety disorders according to the parent reports of the population in the sample.

| Year | Author | Comorbidity Measures | N | Sample Caractheristics | Control Group | Main Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2010 | Mukaddes NM et al. (a)(A) | (K-SADS-PL-T) (Orvaschel and Puig-Antich, 1987) | 60 | AS (30) IQ>70 | AD(30) IQ>70 | (I) AS group displayed greater comorbidity with depressive disorders and ADHD-CT,they also had higher range of IQ score. From a clinical perspective, it could be concluded that both disorders involve a high risk for developing psychiatric disorders, with AS patients at greater risk for depression. |

| 2012 | Simonoff et al. (b)(1) (A,B) | PONS ((Santosh, 2006);SDQ CAPA (Angold& Costello,2000) |

91 | ASD 16 year (91), 12 year (79) | None | (NA) Prevalence of High-SMP was 26,37% (N=24). This study concluded that severe mood problems were associated with current and earlier emotional problems. Intellectual ability and adaptive functioning did not predict to SMP. Relationships between SMP and tests of executive function were not significant after controlling for IQ. |

| 2006 | Person et al. (a) (A,B) | PIC-R (Wirt, 1984). | 51 | AD (26), PDD-NOS (25). Age range:4–18 (M: 10) | None | (NA) After controlling for verbal IQ , the children with AD had significantly more social difficulties, atypical behaviours, and social withdrawal (the core symptoms of autism), than did the children with PDD-NOS No significant differences found between children with PDD-NOS and AD on anxiety symptoms, although both groups approached clinical significance. |

| 2008 | Sukhodolsky et al.(a) (A) | (CASI) (Gadow&Sprafkin, 1997a,b) | 171 | AD (151), AS (6), PDD-NOS (14). Age range: 5–14 (M: 8) [C] |

None | (P) 73 (43%) met screening cut-of criteria for at least one anxiety disorder. Higher levels of anxiety associated with higher IQ, functional language use, and stereotyped behaviours. |

| 2005 | Weisbrot et al. (a) (A) | (ECI-4; Gadow& Sprafkin,1997a) (CSI-4;Gadow&Sprafkin, 2002). (CBCL; Achenbach 1991a), |

483 | PDD-NOS (209), AD (170), AS (104). Age range: 3–12 |

Non-ASD, (326) |

(P) Children with AS earned higher ratings on several anxiety items than children diagnosed with AD. Children with the highest levels of anxiety had higher mean IQ scores than did the low anxious ASD group. |

| 2008 | Simonoff et al.(c) (A,C) | (CAPA) | 112 | AD (62), PDD-NOS (50). Age range:10–14 (M: 11) [R] | None | (NA) 41.9% met criteria for at least one anxiety disorder. ASD diagnosis (AD or PDD-NOS), IQ, and adaptive behaviour were not associated with the presence of an anxiety disorder. These results indicate that anxiety disorders are common in the broader ASD population, not just clinical cases. |

Table 2: Cognitive functioning.

Regarding executive functioning, Hollocks et al. [17] indicated a significant association between poorer executive functioning and higher levels of anxiety, but is not associated with depression. However, Thede & Coolidge [20] found no significant differences in executive functioning between the AS and HFA.

Mukaddes et al. [21] and Simonoff et al. [22] reported information about comorbidity with depressive disorder and severe mood dysregulation and problems (SMP). They used the same sample so the results should not be interpreted independently (Table 2). Simonoff et al. [22] is the one and only study that evaluated the SMP in patients with ASD. They found that intellectual ability and adaptive functioning did not predicted SMP and relationships between SMP and tests of executive function were not significant after controlling for IQ.

| 2014 | Hollocks MJ et al. (1)(a) (A,B,C) | SDQ, PONS | 90 | ASD (90) Range of age: 14-16 | None | (N) Results indicated a significant association between poorer executive functioning and higher levels of anxiety, but not depression. (NA)In contrast, social cognition ability was not associated with either anxiety or depression. This may suggest that poor executive functioning is one factor associated with the high prevalence of anxiety disorder in children and adolescents with ASD. |

| 2006 | Thede and Coolidge(2)(A) | CPNI; (Coolidge, 2002) | 31 | AS (16), HFA (15). Age range: 5–17 (M: 10) | Age, gender matched TD* (31) | (I) Children with AS had more symptoms of anxiety than did children with HFA; 10 of 16 children with AS had elevated GAD scale scores. ASD children (AS and HFA combined) showed greater deficits than the control children on the Executive Function scale of the CPNI. However, there were no significant differences in executive functioning between the AS and HFA children |

Table 2b: Executive functioning.

Global functioning and quality of life

Out of the 25 studies, 5 of them are described in this section. Mattila et al. [23], Mazzone et al. [24] and White et al. [25] focused their primary research question in accordance to the Children’s Global Assessment Scale (CGAS), Farrugia [26] used the life interference measure (LIM) and Van Steensel et al. [27] used the EuroQol-5D.

Four studies reported information about co-morbidity with anxiety disorder [23,25-27]. As it is shown in the table 3, all of these studies used different measures to assess the ASD diagnosis and anxiety comorbidity. In the study of Farrugia [26], the diagnoses from the community were accepted and were not confirmed as part of the study. However, the rest of the studies confirmed the diagnosis with at least one assessment. All the studies with the exception of Mattila et al. [23], all the other studies used different control samples (Table 3). White et al. [25] used ASD with anxiety comorbidity without cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) intervention to compare with a similar sample of patients who were receiving CBT. Regarding the main results, Farrugia [26] found that the correlations among anxiety symptoms, negative automatic thoughts, behavioral problems and overall impairment were significantly higher in the AS group than in either comparison group. In the same way, Mattila et al. [23] found that oppositional defiant disorder (ODD), major depressive disorder and anxiety disorders as comorbid conditions indicated significantly lower levels of functioning. Similarly, in the study of Van Steensel et al. [27] the results showed that higher anxiety severity scores on the ADOS, were associated with a lower quality of life, irrespective of the sample group. Although all of them showed similar results, they used different functionality scales (Table 6). On the other hand, White et al. [25] found that there was no relationship between Developmental Disability (DD)-CGAS scores and parent-reported anxiety scores, adaptive behaviour scores, or educational placement. Mazzone et al. [24] was the only study that considered the association between functioning and depressive symptoms. The results showed that higher levels of depressive symptoms increase the risk of poorer global functioning. There was no significant association between IQ and mood symptoms, behavioural problems or global functioning.

| Year | Author | Comorbidity Measures | N | Sample Caractheristics | Control Group | Main Results | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2012 | Van Steensel FJ et al. (c) (B) | (ADIS-C=P)(Silverman and Albano, 1996) ; CSBQ (ASD-like symptoms) | 115 | ASD (115) Age M:11.37 years | Anxiety D (122) M-Age: 12,79. | (N) Higher anxiety severity scores on the ADIS, as well as higher scores on the CSBQ (ASD-like behaviours), were associated with a lower quality of life, irrespective of group. However, whether anxiety increases ASD (symptoms), ASD (symptoms) cause anxiety, or both (symptoms exacerbating one another), is unclear. The results of this study support a highly similar phenotype of anxiety disorders in children with ASD. No group differences in quality of life were found according to parental or child report. | |

| 2006 | Farrugia et al. (a) (A) | Spence Children's Anxiety Scale (SCAS; Spence, 1998) | 29 | AS. Age range: 12–16 (M: 13) | Anxiety disordered (34);TD (30) | (N)Self-reported symptoms of anxiety were equivalent to those of teens with anxiety disorders; anxiety symptoms, neg. automatic thoughts were significantly higher than in control group. The correlations among anxiety symptoms, negative automatic thoughts, behavioural problems and overall impairment were significantly higher in the AS group than in either comparison group. | |

| 2013 | White et al. (d) (B) | CATS; Schniering&Rapee, 2002) | 30 | ASD + Anxiety Disorder.(15) CBT 14 weeks treatment | ASD + Anxiety Disorder (15) | (NA)DD-CGAS scores were strongly correlated with parent-reported degree of ASD-related impairment and pragmatic communication. Contrary to what we hypothesized, there was no relationship between DD-CGAS scores and parent-reported anxiety scores, adaptive behaviour scores, or educational placement.DD-CGAS scores were also negatively correlated with verbal IQ, as expected. | |

| 2010 | Mattila ML et al. (b) (B) | Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule–Child/Parent Version (ADIS-/P) | 50 | ASD/AS (50) Range of age (9-16) | None | (N)The results support common (prevalence 74%) and often multiple comorbid psychiatric disorders in AS/HFA; behavioral disorders were shown in 44%, anxiety disorders in 42% and tic disorders in 26%. Oppositional defiant disorder, major depressive disorder and anxiety disorders as comorbid conditions indicated significantly lower levels of functioning. | |

| 2013 | Mazzone et al. (b) (A,B) | (K-SADS-E) | 30 | AS/HFA (30) | Major Depression (30) TD (35) | (N)The presence of internalizing symptoms was reported in 18,9% of the AS/HFA group, in 18,9% of the MD group and in 3,9 % of the TD group. AS/HFA group reported higher depression symptoms compared to the TD group. Higher level of depression symptoms increases the risk of poorer global functioning. There was no significant association between IQ and mood symptoms, behavioural problems or global functioning. | |

Functioning Measures: (a) The Life Interference Measure (LIM; Lyneham et al. 2003) ; (b) Children Global assessment Scale (CGAS)(Shaffer et al.,1983)

; (c) The EuroQol-5D (EuroQol group, 1990); (d) DD-CGAS(Wagner et al,2007) . ASD Diagnosis :(A)Clinical Diagnosed (DSM-IV ). (B) ADI-R (Le Couteur

et al., 1989) and/or ADOS-G (Lord et al., 2000). Correlation: (P) Positive (comorbidity is associated with high functionality) (I) Inconsistent (with the

goal of this review) (N) Negative (comorbidity is associated with poor functionality) (NA) No association.

Table 3: Global functioning and quality of life.

| Year | Author | Comorbidity Measures | N | Sample Characteristics | Control Group | Main Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2006 | Meyer et al. (D) (a) | BASC (Reynolds &Kamphaus, 1998) | 31 | AS. Age range: 7–13 (M: 10) | TD (33) | (N)This study examined the associations between information processing, social functioning and psychological functioning, including co-occurring psychiatric disorders.Teens with AS and their parents reported higher levels of anxiety than did the control group.Anxiety was related to deficits in social awareness and experience. Cognitive and social-cognitive abilities were associated with aspects of social information processing tendencies, but not with emotional and behavioural difficulties |

| 2006 | Belliniet al. (A)*(b) | (SAS-A; LaGreca, 1999); (MASC; March, 1999) | 41 | AD (19), AS (16), PDD-NOS (6). Age range: 12–18 (M: 14); No MR | None | (N)Social skill deficits and physiological hyperarousal combined, contributed to variance in symptoms of social anxiety in teens with ASD. |

| 2013 | Joshi G et al. (C) (c,d) | (CBCL) (Achenbach, 1991)(K-SADS-E)) | 155 | BD+ASD(47) | BD (155) | (I)Thirty percent (47/155) of the bipolar I probands met criteria for ASD. The age at onset of bipolar I disorder was significantly earlier in the presence of ASD comorbidity and significantly poorer GAF scores than BPD-I probands. BPD-I + ASD probands had significantly more impaired scores on all CBCL subscales compared to BPD-I probands except for the somatic complaints scale. However Bipolar I probandshas significantly poorer SAICA scores independent of comorbid with ASD. Bipolar I disorder comorbidity with ASD represents a very severe psychopathologic state in youth. |

| 1997 | Wozniak J. et al. (C) (c) | (K-SADS-E) ; (CBC [Achenbach, 1991] | 190 | PDD + mania (14), mania without PDD (114) | PDD without mania ( 52) | (N)The 14 children with both PDD + mania represented 21% of the PDD subjects and 11% of all manic subjects. Functioning of children with PDD+mania was very poor as evidenced by their scores on the SAICA, GAF and CBCL clinical subscales.These scores, plus the high rate of hospitalization associated, suggest that PDD+maniais a highly disabling condition, warranting further study and attention. |

| 2010 | Bauminger N et al. (A,B) (e) | (CBC) | 77 | HFA (23) Israel HFA (20) USA Rate of age (8-12) | TD(22)Israel, TD (20) USA | (I)Children with ASD exhibited significantly greater levels of psychopathology as assessed by the CBC and parents of children with ASD exhibited higher parenting stress as assessed by the Parenting Stress Index [Abidin, 1995]. Parenting stress emerged as the most important predictor of children's I-E problems. |

Functioning Measures: (a) Social encoding errors on the video and Why Kids Do Things (WKDT: Crick and Dodge,1996) (b) Physical Symptoms subscale of MASC and The Social Skills Rating System (SSRS; Gresham & Elliot,1990) (c) [Social Adjustment Inventory for Children and Adolescents (SAICA) (Orvaschel and Walsh, 1984), Global Functioning (GAF) (d) Moos family environment Scale (FES).(Moos RH et al. 1974) ; (e) Mother–child relationship qualities.[Inventory of Parent and Peer Attachment [IPPA;Armsden & Greenberg, 1987]. ASD Diagnosis:(A)Clinical Diagnosed (DSM-IV ). (B) ADI-R (Le Couteur et al., 1989) and/ or ADOS-G (Lord et al., 2000) (C) Diagnosis based on DSM-III-R criteria.(D) Autism Spectrum Screebibg Questionare (ASSQ: Enlers et al.,1999) and Australian Scale for Asperger´s Syndrome (ASAS: Attwood,1998) *Previous diagnosis. Correlation: (P) Positive (comorbidity is associated with high functionality) (I) Inconsistent (with the goal of this review) (N) Negative (comorbidity is associated with poor functionality) (NA) No association.

Table 4: Psychosocial and family functioning.

| Year | Author | Comorbidity Measures | N | Sample Caractheristics | Control Group | Main Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2005 | Gadow et al. (A) (a) | (CSI-4; Gadow&Sprafkin, 2002) | 301 | AD.(103), AS (80), PDD-NOS (118). Age range: 6–12 (M: 8); Clinic referrals |

Non-ASD referrals (181); regular ed (404); special ed (60) |

(NA)25.2% and 19.5% of males and females, respectively, with ASD screened positive for generalized anxiety disorder.The authors reported that severity of ASD appeared to be negatively associated with psychiatric symptoms such that children with AD were generally rated as having fewer and less severe psychiatric symptoms. |

| 2004 | Bradley et al.(B) (b) | (DASH-II; Matson, 1995) | 12 | AD. Age range: 12–20 (M: 16); FSIQb75 [M] |

Learning disabled (17) TD (16) |

(I)42% (n=5) of sample reached clinical significance for anxietyproblems, compared to 0% of mentally retarded sample withoutautism.The children with AD had an average of 5.25 clinically significant disorders (excluding AD) based on cut-off scores on the DASH-II, compared to an average of 1.25 for the non-AD group. |

| 2013 | Van Steensel FJ et al. (A,B) (c) | (ADIS-C=P) | 73 | ASD+ Anxiety D-group ( 73) | Anxiety-Group (34) | (I)The mean of severity score of an anxiety disorder did not differ between theASD+AD- and AD-group. For the ASD-subtypes (autistic disorder, Asperger’s disorder or PDD-NOS), no differences were found with respect to the number of anxiety disorders, anxiety severity scores, or the presentation of anxiety disorders. |

| 2013 | Simonoff et al (A,B) (d) | (SDQ). (CAPA) | 81 | ASD (81) 12-16-year | None | (N)Prevalence for emotional problem was 34,5 % at 12 years and 30,7 % at 16 years. Lower IQ and adaptive functioning predicted higher hyperactivity and total difficulties scores. Greater emotional problems at 16 were predicted by poorer maternal mental health, family-based deprivation and lower social class. |

| 2005 | Pfeiffer et al.(A) (e) | (RCMAS; Reynolds & Richmond, 1978) and (CDI; Kovacs, 1978)- Parent Version | 50 | AS. Age range: 6–17 (M: 9) | None | (NA)There were no significant relationships between depression and overall adaptive behaviouror anxiety and overall adaptive behaviour. However, the data supports positive relationships between anxiety and sensory defensiveness in all age ranges and a relationship between depression and hyposensitivity in older children. Stronger inverse relationships were apparent between specific adaptive behaviours including: (a) symptoms of depression and functional academics, leisure, social skills; (b) anxiety and functional academics; and (c) both sensory hyper- and hyposensitivity and community use and social skills). |

| 2012 | Gadow et al.(A,B) (a) | (CSI-4) , (DICA-P; Reich 2000) | 287 | ASD + ADHD (74), ASD/-ADHD(107), CMTD+ADHD (47), ADHD Only( 59) | TD (Mother) (169) (Tearcher) (173) |

(I)The ASD group obtained more severe ratings for all depression symptoms from both, mother and teacher than controls. They also found little relation between IQ or verbal ability and global depression scores in children with ASD. Severity of depressionsymptoms was for the most part comparable for boys with ASD with and without ADHD, which raises a number of interesting questions about pathogenic processes that result in ASD and their role in mood dysregulation as well as criteria for depression in ASD. |

| 2007 | Munesue T et al. (C) (d) | Hospital according to DSM-IV | 44 | HFA + MD (16) Range of Age (12-29) | HFA (28) Range of age (8-38) | (N)Sixteen patients (36.4%) were diagnosed with mood disorder (MD). The major comorbid mood disorder in patients with high-functioning ASD is bipolar disorder and not major depressive disorder. Rate of mood disorder in first- and second-degree relatives, and IQs were not significantly different between the two groups. Patients with mood disorder showed significantly lower scores on TABS than those without mood disorder, although scores on ASSQ and AQ were not significantly different between the two groups. |

Symptoms severity: (a) CSI-4; Gadow & Sprafkin, 2002) (b) DASH-II; Matson, 1995 (c) Anxiety Severity score (ADIS-C=P) (d) Adaptative Functioning.

(Vineland Adaptive Behaviour Scales composite score) (e) Sensory Profile for children (Dunn, 1999). The Adolescent/Adult Sensory Profile (Brown

& Dunn, 2002) ,Adaptive Behavior Assessment System: Parent Version. (ABAS) and (SFA) (Dunn, 1999) (d) Severity of Autism [ Score of TABS, ASSQ

and AQ). ASD Diagnosis: (A)Clinical Diagnosed (DSM-IV ). (B) ADI-R (Le Couteur et al., 1989) and/or ADOS-G (Lord et al., 2000) (C) (TABS; Kurita

and Miyake, 1990), (ASSQ; Ehlers et al., 1999), and (AQ; Baron-Cohen et al., 2001). Correlation: (P) Positive (comorbidity is associated with high

functionality) (I) Inconsistent (with the goal of this review) (N) Negative (comorbidity is associated with poor functionality) (NA) No association.

Table 5: Symptoms severity and adaptive functioning

Psychosocial and/or family functioning

Out of the 25 studies, 5 of them [28-32], focused their primary research question accordingly with the psychosocial or family functioning. The measures used for assessing this sort of functioning were very heterogeneous between the different studies (Table 6). Only Bauminger et al. [32] focused their main functioning assessment on family evaluation.

| Year | Author | Functionality | Functionality Measures |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2010 | Mukaddes NM et al. | Cognitive | Rate of Cognitive Functioning (IQ, Verbal IQ, Performance IQ) (WISC-R) |

| 2012 | Simonoff et al. Cognitive&Executive | Rate of cognitive function (IQ ). Vineland Adaptive Behaviour Scales composite score &card sort and trail making | |

| 2005 | Weisbrot et al. | Cognitive & Severity | Range of Cognitive functioning (IQ) & Early Childhood Inventory-4 and Scoring formats for DSM-IV criteria. |

| 2006 | Person et al. | Social & Cognitive | Emotional functioning and Social Skills: Personality Inventory for Children-Revised (Subscale Scores) &Rate of cognitive functioning: Verbal IQ |

| 2008 | Sukhodolsky et al. | Cognitive | Range of cognitive functioning ( IQ,functional language use, and stereotyped behaviors.) |

| 2008 | Simonoff et al. | Cognitive | WISC-III UK version,30 Raven_s Standard matrix (SPM) orColoured Progressive matrices (CPM) |

| 2006 | Thede and Coolidge | Executive | Parent-report measures of psychological and executive functioning: Coolidge Personality and Neuropsychological Inventory. |

| 2014 | Hollocks MJ et al. | Cognitive & Executive | (Wechsler,1999)] Social cognitive Measure [Frith-Happé animations (Abell, Happe, & Frith, 2000; Castelli, Frith, Happe, & Frith, 2002, Strange stories (Happé, 1994),&Opposite worlds, Trail making [Reitan, 1958], Numbers backwards, Card sorting task. |

| 2012 | Van Steenselet al. | Quality of Life (QoL) | EuroQol-5D |

| 2006 | Farrugia et al | Severity &QoL | Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ; Goodman,1997)& Life Interference Measure (LIM; Lyneham, Abbott, &Rapee, 2003) |

| 2013 | White et al. | Global & Severity | DD-CGAS(Wagner et al,2007), Clinical Global Impresions-Improvement (CGI-I), &Children Comunication Checklist-2(CCC-2) Child and Adolescent Symptom Inventory ASD Anxiety Scale, Social Responsiveness Sacle, Vineland Adaptative Behaviour Scale. Scholl placement. |

| 2010 | Mattila ML et al. | Global | [Children's Global Assessment Scale(GAF)] |

| 2013 | Mazzone et al | Global &Cognitive | Children Global assessment Scale (CGAS)(Shaffer et al.,1983)& Rate of cognitive functioning (IQ) |

| 2006 | Meyer et al. | Social | Range of cognitive and Social cognitive ability: Social encoding errors on the video and Why Kids Do Things (WKDT: Crick and Dodge,1996) |

| 2006 | Bellini | Social | Physiological arousal (Physical Symptoms subscale of MASC) and The Social Skills Rating System (SSRS; Gresham & Elliot,1990) |

| 2013 | Joshi G et al. | Social & Global & Family | Psychosocial functioning [Social Adjustment Inventory for Children and Adolescents (SAICA) (Orvaschel and Walsh, 1984) &(GAF) &(FES).(Moos RH et al. 1974)] |

| 1997 | Wozniak J. et al. | Social & global | Psychosocial functioning [Social Adjustment Inventory for Children and Adolescents (SAICA) (Orvaschel and Walsh, 1984) & GAF |

| 2010 | Bauminger N et al. | Cognitive & Family | (VIQ of 80 or Peabody Picture and Vocabulary Test [PPVT;Dunn& Dunn, 1997] & Mother–child relationship qualities. [IPPA;Armsden& Greenberg, 1987]. |

| 2005 | Gadow et al. | Severity | Child Symptom Inventory-4 (CSI-4; Gadow&Sprafkin, 2002) |

| 2004 | Bradley et al. | Severity | Diagnostic Assessment for the Severely Handicapped (DASH-II; Matson, 1995) |

| 2013 | Van Steenselet al. | Severity | Anxiety Severity score (ADIS-C=P): ranging from 0 to 8, and summing the ratings of all anxiety disorders. |

| 2013 | Simonoff et al | Cognitive & Adaptive | Rate of cognitive function (IQ) and Adaptative Functioning. (Vineland Adaptive Behaviour Scales composite score |

| 2005 | Pfeiffer et al. | Adaptive | Sensory Profile for children (Dunn, 1999). The Adolescent/Adult Sensory Profile (Brown & Dunn, 2002) Adaptive Behavior Assessment System: Parent Version. (ABAS) School Function Assessment (SFA) (Dunn, 1999) |

| 2012 | Gadow et al. | Severity & Cognitive | Severity of Symtoms [Child Symptom Inventory-4 (CSI-4)] Neuropsychological Measures [The Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence (Wechsler,1999)] |

| 2007 | Munesue T et al. | Severity & cognitive | Rate of Cognitive Functioning [Wechsler Intelligence Scale (FIQ,VIQ,PIQ) ] Severity ofAutism [ Score of TABS, ASSQ and AQ) |

Table 6: Functionality measures.

Joshi et al. [28] and Wozniak & Biederman [31] focused on mood disorder in patients with ASD and the impact on the functionality. The diagnostic measures were similar on both studies. However, as it is shows in the table 4, the samples characteristics and the control group were very different. Regarding the main results, Joshi et al. [28] examined not only the social functioning, but also the clinical and familiar correlates of bipolar disorder when it occurs with and without ASD comorbidity in a well-characterized, research-referred population of youth with bipolar disorder. Wozniak & Biederman [31] systematically investigated the overlap between mania and PDD in a consecutive sample of referred youths, examining its prevalence and correlates. According with the purpose of this review, the results found by Joshi et al. [28] were inconsistent. Wozniak & Biederman [31] found that the functioning of children with PDD+ mania was poorer than PDD group, as evidenced by their scores on the social adjustment inventory for children and adolescents (SAICA) and the global assessment of functioning (GAF) (Table 6).

The rest of the studies described in this section assessed the association between the social functioning and its comorbidity with anxiety [29,30,32]. They used different ASD diagnostic agreements (Table 4). According with the main results, Meyer et al. [29] concluded that anxiety was related to deficits in social awareness and experience. In the opposite effect direction, Bellini [30] found that physiological arousal and social skills deficits combined contributed to a significant variance in symptoms of social anxiety. Finally, Bauminger et al. [32] investigated the relationship between internalizing and externalizing (I-E) behaviors and family variables, including both parenting stress and quality of attachment relations. The results were inconsistent according with the purpose of this review (Table 4).

Measures of symptoms severity or adaptive functioning

In the last section, we found 7 studies that describe the impact on the functionality through the severity of symptoms, using a range variability of measures (Table 5).

Bradley et al, [33], Van Steensel et al. [34] and Gadow et al. [35] evaluated the comorbidity with anxiety disorders. The sample of patients and the diagnosis measures were also very different (Table 5). According to the main results found on their studies, Gadow et al. [35] reported that the severity of ASD appeared to be negatively associated with psychiatric symptoms. The following studies were inconsistent relating to this review; Bradley et al. [33] concluded that the children with AD had an average of 5.25 clinically significant disorders based on cut-off scores on the diagnostic assessment of the severely handicapped-II (DASH-II) (Table 6) compared to an average of 1.25 for the non-AD group. The goal of the Van Steensel et al. [34] study was to estimate the societal costs of children with high-functioning ASD and comorbid anxiety disorder and to explore whether costs are associated with the type/severity of ASD or anxiety disorder. They found that the mean of severity score of an anxiety disorder did not differ between the ASD+ anxiety disorder and anxiety disorder group.

Regarding comorbidity with mood disorders, we found 3 studies [2,36,37]. As we can see in table 5, they used very different samples, diagnosis and control groups. Relating to the main results, Simonoff et al. [36] and Munesue et al. [37] found more consistent results than Gadow et al. [2] (Table 5). Simonoff et al. [36] concluded that lower IQ and adaptive functioning predicted higher hyperactivity and total difficulties scores. In the same way, Munesue et al. [37] established that patients with mood disorder showed significantly lower scores on the Tokyo autistic behaviour scale (TABS) (table 6) than those without mood disorder.

Finally, Pfeiffer et al. [38] was the only study that evaluated both, comorbidity between anxiety and depression disorder. They found that there were no significant relationships between depression and overall adaptive behaviour or anxiety and overall adaptive behaviour.

Discussion

Based on the data presented in these studies collectively, there is no doubt that emotional problems are quite prevalent in young people with ASD. Variables such as specific ASD diagnosis, level of cognitive and global functioning, degree of social and family impairment, adaptive functioning and severity of symptoms likely have an influence on the individual's experience of emotional problems. Unfortunately, there is little clarity on how best to assess the functionality in this population and the direct impact of the emotional disorders in the youth patients with ASD functioning. The studies summarized in this review have addressed a broad range of questions about the functionality impact of emotional disorders in young people with ASD. The main strength of this review is that our intent was to not only summarize the available empirical literature, but also emphasize the need for consistent future research.

Methodology issues

By addressing methodological issues that limit the findings of the extant literature, future studies can contribute noticeably to our better understanding of the impact of emotional disorders in this population and answer more pointed scientific questions. Many of the reviewed studies [e.g.,[17,22,33]], reported using ‘gold standard’ diagnostic tools for ASD [i.e., ADI-R [14] and ADOS [15]]. Some studies did not employ any independent confirmation of the diagnoses, instead they included children based solely on previous clinical diagnoses of ASD [e.g.,[21,26, 30]]. Other studies, such as Gadow et al. [35], used rigorous diagnostic evaluation procedures (e.g., interview, observations) and established inter-diagnostician reliability, but did not use the ADI-R or ADOS, which were designed specifically for the assessment of autism and other spectrum conditions.

The studies reviewed demonstrated little consistency in terms of how comorbidity disorders were measured. Research on the applicability of traditional measures of childhood emotional symptoms is sorely needed. If valid and reliable measures cannot be identified, new measures will need to be developed in order to accurately capture symptoms of emotional problems in people with ASD. For example, previous reports have supported the validity of the mania diagnosis in non-PDD children when examining clinical correlates [31] as well as external validators such as the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) [39], but not in PDD children. Until we have consensus on ‘best practice’ measurements, a healthy scepticism is called, with respect to the precision of the tools we currently have for measuring childhood emotional problems when evaluating children with ASD. In the same way, the functionality measures described in this review were very heterogeneous and with a widespread variability across the different studies. Further research is necessary for assess the impact on functionality (global scores, cognitive, social, adaptive functioning. etc.) in this population.

A methodological concern seen in most of the studies is the inclusion of mixed ASD samples, comprised of youth with AD, AS, and PDD-NOS. Also, given differences in cognitive functioning usually associated with ASD subtypes, future studies should examine how diagnosis might independently be associated with emotional disorders.

The majority of the studies reviewed used clinic-based samples [e.g.,[30,35]] or samples recruited from a variety of other sources (e.g., autism support groups) [e.g., [18,38]]. In contrast, Simonoff et al. [11] drew their ASD sample from a large population-derived, non-clinical cohort. Clinical samples are often needed to accrue an adequate number of participants and for ensuring statistical power, but such samples can make it difficult to generalize findings. Clinical-based samples are likely not representative of all children with ASD in many important aspects, such as degree of parental investment, level of behavior disturbance, and previous treatment exposure. Further studies using non-clinical, community based and school samples are needed to evaluate the prevalence and the impact of emotional disorders in the broader ASD population.

Other limitation of this study is related to the fact that the majority of them are cross-sectional [e.g.,[24,29]] and to understand the developmental change and to clarify the clinical phenotypic manifestation across the lifespan and the direction of the association between the risk factors (emotional disorders) and the outcome (functionality) [e.g.,[30,32]] longitudinal studies are needed. For example, the results of the study of Bauminger et al. [32] were inconsistent because they concluded that parenting stress emerged as the most important predictor of children's I-E problems but, the inverse association between the impact of the I-E problems in the parenting stress were not analyzed.

Main results

The most important clinically relevant question in this review is the degree to which emotional disorders in children with ASD, affect the functionality of their lives, in other words, how co-occurring emotional problems affect the prognosis for the functionality in children with ASD. For answering this question, our study found only three primary studies, White et al. [25], Wozniak & Biederman [31] and Munesue et al. [37], in which they compared the functionality between a group of patients with ASD+ and emotional disorders and a group of patients with ASD without the emotional disorders. They studied the comorbidity with anxiety disorder, mania and mood disorders respectively. Wozniak & Biederman [31] and Munesue et al. [37] determined a significant negative association between ASD and the comorbidity with emotional disorders. These results were consistent with our hypothesis; affecting considerably the functionality scores. According with the study of White et al. [25], they supported the importance of assessing global functioning in addition to symptom change and treatment response in clinical trials. In a previous review, White et al. [40] obtained the anxiety comorbidity estimated ranging from 11% to 84%.

The secondary studies provided more information about the impairment in patients with ASD and emotional disorders, but the association with a comparative group of patients with ASD and without the risk factors is needed.

Cognitive ability for children with ASD can range from low to high across any range of severity for the condition [41,42]. Lower IQ may interact with the severity of the child’s autism to increase the need for assistance with activities of daily living [43]. Intellectual disability (ID) is one of the most common co-occurring disorders in ASD [44,45] and is an important predictor of outcome [5-8]. Several research studies have established the impact of general IQ on adaptive (daily life) functions in ASD samples [46], but little is known in relation with the impact of comorbid disorders on cognitive functions in this population. According with the results of this review, there is controversy in the conclusions across the different studies. The results of some studies indicated that children with ASD may experience anxiety symptoms which are similar to those seen in non-ASD clinical samples, but that the presentation of anxiety symptoms in this population may be affected by cognitive functioning. Thus, Sukhodolsky et al. [16] found that children with higher IQ and greater social impairment experience the most severe anxiety. This hypothesis is reinforced by Gadow et al. [35] and Weisbrot et al. [19]. On the other hand, Simonoff et al. [11], Pearson et al. [18] and Simonoff et al. [22] found no significant association. Mazzone et al. [24] supported this hypothesis; they concluded that there was no significant association between IQ and mood symptoms, behavioural problems or global functioning.

Regarding executive functioning, Hollocks et al. [17] contrarily to Thede & Coolidge [20] suggested that poor executive functioning is one factor associated with the high prevalence of anxiety disorder in children and adolescents with ASD.

Assessment of global functioning is an important consideration in treatment outcome research; yet, there is little guidance on its evidence-based assessment for children with ASD [25]. Outcome measures sensitive to change in global functioning designed for use in the ASD population are needed [47]. Wagner et al. [48] addressed this need by modifying the CGAS [49]. In this review, many studies showed that higher anxiety severity, major depression, mania and bipolar disorder as comorbid conditions indicated significantly lower levels of functioning or lower quality of life [23,24,27,28,31]. In contrast, the only primary study of White et al. [25] found no relationship between DD-CGAS and anxiety scores.

Concerning to psychosocial functioning and according with the primary study of Wozniak & Biederman [31], there was a negative correlation between comorbidity with mania and scores on the SAICA. Using different measures, Meyer et al. [29] and Bellini [30] supported this finding, but they studied anxiety comorbidity. Alternatively, Hollocks et al. [17] found that social cognition ability was not associated with either anxiety or depression.

Relating to symptoms severity and adaptive functioning, (Table 5) the majority of the studies were inconsistent with the objective of this review. Only Simonoff et al. [36] and Munesue et al. [37] found a consistent correlation. In examining the role of risk factors, Simonoff et al. [36] found that lower IQ and adaptive functioning predicted higher hyperactivity and total difficulties scores., in addition, Munesue et al. [37] concluded that mood disorder showed significantly lower scores on the TABS [50], than those without mood disorder, although scores on highfunctioning autism spectrum screening questionnaire (ASSQ) [51], and autism-spectrum quotient (AQ) [52], were not significant. A limitation of these studies was that the clinical scientists often used measures that targeted specific problem areas (e.g. anxiety, depression, aggressive behaviour) rather than global functioning, and most often, these measures have been developed for individuals without ASD [53,54]. Because individuals with ASD do not typically present a unified, prominent problematic symptom or behaviour, but rather a myriad, a narrow focus on improvement in a single symptom domain may fail to capture the full range of possible functioning or change. Although measuring change in the targeted behavioural domains is methodologically necessary, future research is needed because the full range of a participant’s abilities and deficits may not be captured if global measures are not included.

Conclusion

Children with ASD and emotional disorders may suffer from two disorders. Comorbid with emotional disorders among patients with ASD may be more common than previously thought. It may have consequent impairment in their psychological profile, social adjustment, adaptive functionality, cognitive and global functioning and should alert clinicians to the importance of assessing mood disorders in order to choose the appropriate treatment. Identification of the comorbid condition may have important therapeutic and scientific implication. Future researches are needed to understand how emotional disorders develop and how they may interact with the score of functioning in this population.

References

- American Psychiatric Association, A (2000) Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (IV-R ed.).

- Gadow KD, Guttmann-Steinmetz S, Rieffe C, Devincent C J (2012) Depression symptoms in boys with autism spectrum disorder and comparison samples. J Autism Dev Disord 42: 1353-1363.

- Gadow KD, DeVincent CJ, Pomeroy J, Azizian A (2004) Psychiatric symptoms in preschool children with PDD and clinic and comparison samples. J Autism Dev Disord 34: 379-393.

- Sverd J, Dubey DR, Schweitzer R, Ninan R (2003) Pervasive developmental disorders among children and adolescents attending psychiatric day treatment. Psychiatr Serv 54: 1519-1525.

- Wallace KS, Rogers SJ (2010) Intervening in infancy: implications for autism spectrum disorders. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 51: 1300-1320.

- Howlin P, Goode S, Hutton J, Rutter M (2004) Adult outcome for children with autism. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 45: 212-229.

- Fountain C, Winter AS, Bearman PS (2012) Six developmental trajectories characterize children with autism. Pediatrics 129: e1112-1120.

- Billstedt E, Gillberg C, Gillberg C (2005) Autism after Adolescence: Population-based 13- to 22-year Follow-up Study of 120 Individuals with Autism Diagnosed in Childhood. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 35: 351-360.

- Allik H, Larsson JO, Smedje H (2008) Sleep patterns in school-age children with Asperger syndrome or high-functioning autism: a follow-up study. J Autism Dev Disord 38: 1625-1633.

- Mugno D, Ruta L, D'Arrigo VG, Mazzone, L (2007)Impairment of quality of life in parents of children and adolescents with pervasive developmental disorder. Health Qual Life Outcomes 5: 22.

- Simonoff E, Pickles A, Charman T, Chandler S, Loucas T, Baird G (2008) Psychiatric disorders in children with autism spectrum disorders: prevalence, comorbidity, and associated factors in a population-derived sample. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 47: 921-929.

- Ghaziuddin M, Ghaziuddin N, Greden J (2002) Depression in persons with autism: implications for research and clinical care. J Autism Dev Disord 32: 299-306.

- Grzadzinski R, Huerta M, Lord C (2013) DSM-5 and autism spectrum disorders (ASDs): an opportunity for identifying ASD subtypes. Mol Autism 4: 12.

- Lord C, Rutter M, Le Couteur A (1994) Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised: a revised version of a diagnostic interview for caregivers of individuals with possible pervasive developmental disorders. J Autism Dev Disord 24: 659-685.

- Lord C, Risi S, Lambrecht L, Cook EH Jr, Leventhal BL, DiLavore PC, Rutter M (2000) The autism diagnostic observation schedule-generic: a standard measure of social and communication deficits associated with the spectrum of autism. J Autism Dev Disord 30: 205-223.

- Sukhodolsky D, Scahill L, Gadow K, Arnold LE, Aman M, McDougle C, Vitiello B (2008) Parent-Rated Anxiety Symptoms in Children with Pervasive Developmental Disorders: Frequency and Association with Core Autism Symptoms and Cognitive Functioning. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology 36: 117-128.

- Hollocks MJ, Jones CR, Pickles A, Baird G, Happe F, Charman T, Simonoff E (2014) The association between social cognition and executive functioning and symptoms of anxiety and depression in adolescents with autism spectrum disorders. Autism Res 7: 216-228.

- Pearson DA, Loveland KA, Lachar D, Lane DM, Reddoch SL, Mansour R, Cleveland LA (2006) A comparison of behavioral and emotional functioning in children and adolescents with Autistic Disorder and PDD-NOS. Child Neuropsychol 12: 321-333.

- Weisbrot DM, Gadow KD, DeVincent CJ, Pomeroy J (2005) The presentation of anxiety in children with pervasive developmental disorders. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 15: 477-496.

- Thede L, Coolidge F (2007) Psychological and Neurobehavioral Comparisons of Children with Asperger’s Disorder Versus High-Functioning Autism. J Autism Dev Disord 37: 847-854.

- Mukaddes NM, Herguner S, Tanidir C (2010) Psychiatric disorders in individuals with high-functioning autism and Asperger's disorder: similarities and differences. World J Biol Psychiatry 11: 964-971.

- Simonoff E, Jones CR, Pickles A, Happe F, Baird G, Charman, T (2012) Severe mood problems in adolescents with autism spectrum disorder. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 53: 1157-1166.

- Mattila ML, Hurtig T, Haapsamo H, Jussila K, Kuusikko-Gauffin S, Kielinen M, Moilanen I (2010) Comorbid psychiatric disorders associated with Asperger syndrome/high-functioning autism: a community- and clinic-based study. J Autism Dev Disord 40: 1080-1093.

- Mazzone L, Postorino V, De Peppo L, Fatta L, Lucarelli V, Reale L, Vicari S (2013) Mood symptoms in children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorders. Res Dev Disabil 34: 3699-3708.

- White SW, Smith LA, Schry AR (2014) Assessment of global functioning in adolescents with autism spectrum disorders: utility of the Developmental Disability-Child Global Assessment Scale. Autism 18: 362-369.

- Farrugia S, Hudson J (2006) Anxiety in adolescents with Asperger syndrome: Negative thoughts, behavioral problems, and life interference. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities 21: 25-25.

- Van Steensel FJ, Bogels SM, Dirksen CD (2012) Anxiety and quality of life: clinically anxious children with and without autism spectrum disorders compared. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol 41: 731-738.

- Joshi G, Biederman J, Petty C, Goldin RL, Furtak SL, Wozniak J (2013) Examining the comorbidity of bipolar disorder and autism spectrum disorders: a large controlled analysis of phenotypic and familial correlates in a referred population of youth with bipolar I disorder with and without autism spectrum disorders. J Clin Psychiatry 74: 578-586.

- Meyer JA, Mundy PC, Van Hecke AV, Durocher, JS (2006) Social attribution processes and comorbid psychiatric symptoms in children with Asperger syndrome. Autism 10: 383-402.

- Bellini (2006) The development of social anxiety in adolescents with autism spectrum disorders. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities 21: 138.

- Wozniak J, Biederman J (1997) Mania in children with PDD. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 36: 1646-1647.

- Bauminger N, Solomon M, Rogers SJ (2010) Externalizing and internalizing behaviors in ASD. Autism Res 3: 101-112.

- Bradley EA, Summers JA, Wood HL, Bryson SE (2004) Comparing rates of psychiatric and behavior disorders in adolescents and young adults with severe intellectual disability with and without autism. J Autism Dev Disord 34: 151-161.

- Van Steensel FJ, Dirksen CD, Bogels SM (2013) A cost of illness study of children with high-functioning autism spectrum disorders and comorbid anxiety disorders as compared to clinically anxious and typically developing children. J Autism Dev Disord 43: 2878-2890.

- Gadow KD, Devincent CJ, Pomeroy J, Azizian A (2005) Comparison of DSM-IV symptoms in elementary school-age children with PDD versus clinic and community samples. Autism 9: 392-415.

- Simonoff E, Jones CR, Baird G, Pickles A, Happe F, Charman T (2013) The persistence and stability of psychiatric problems in adolescents with autism spectrum disorders. J Child Psychol Psychiatry, 54: 186-194.

- Munesue T, Ono Y, Mutoh K, Shimoda K, Nakatani H, Kikuchi M (2008) High prevalence of bipolar disorder comorbidity in adolescents and young adults with high-functioning autism spectrum disorder: a preliminary study of 44 outpatients. J Affect Disord 111: 170-175.

- Pfeiffer B, Kinnealey M, Reed C, Herzberg G (2005) Sensory modulation and affective disorders in children and adolescents with Asperger's disorder. Am J Occup Ther 59: 335-345.

- Achenbach TM (1991) Integrative guide for the 1991 CBCL/4-18, YSR and TRF profiles. University of Vermont.

- White SW, Oswald D, Ollendick T, Scahill L (2009) Anxiety in children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorders. Clin Psychol Rev 29: 216-229.

- Coplan J, Jawad, AF (2005) Modeling clinical outcome of children with autistic spectrum disorders. Pediatrics 116: 117-122.

- Coplan J, Souders MC, Mulberg AE, Belchic JK, WrayJ, JawadAF, Levy SE (2003) Children with autistic spectrum disorders. II: parents are unable to distinguish secretin from placebo under double-blind conditions. Arch Dis Child 88: 737-739.

- Payakachat N, Tilford JM, Kovacs E, Kuhlthau K (2012) Autism spectrum disorders: a review of measures for clinical, health services and cost-effectiveness applications. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res 12: 485-503.

- Matson JL, Shoemaker M (2009) Intellectual disability and its relationship to autism spectrum disorders. Res Dev Disabil 30: 1107-1114.

- Fernell E, Hedvall A, Norrelgen F, Eriksson M, Hoglund-Carlsson L, Barnevik-Olsson M, Gillberg C et al. (2010) Developmental profiles in preschool children with autism spectrum disorders referred for intervention. Res Dev Disabil 31.

- Schatz J, Hamdan-Allen G (1995) Effects of age and IQ on adaptive behavior domains for children with autism. J Autism Dev Disord 25: 51-60.

- Volkmar F, R B a D P (2011) Evidence-Based Practices and Treatments for Children with Autism. New York. 365-391.

- Wagner A, Lecavalier L, Arnold LE, Aman MG, Scahill L, Stigler KA, Vitiello B (2007) Developmental disabilities modification of the Children's Global Assessment Scale. Biol Psychiatry, 61: 504-511.

- Shaffer D, Gould MS, Brasic J, Ambrosini P, Fisher P, Bird H, Aluwahlia S (1983) A children's global assessment scale (CGAS). Arch Gen Psychiatry 40: 1228-1231.

- KuritaH, Hiyake Y (1990) The reliability and validity of the Tokyo Autistic Behaviour Scale. Jpn J Psychiatry Neurol 44: 25-32.

- Ehlers S, Gillberg C, Wing L (1999) A screening questionnaire for Asperger syndrome and other high-functioning autism spectrum disorders in school age children. J Autism Dev Disord 29: 129-141.

- Baron-Cohen S, Wheelwright S, Skinner R, Martin J, Clubley E (2001) The autism-spectrum quotient (AQ): evidence from Asperger syndrome/high-functioning autism, males and females, scientists and mathematicians. J Autism Dev Disord 31: 5-17.

- Lecavalier L, Wood JJ, Halladay AK, Jones NE, Aman MG, Cook EH, Scahill, L (2014) Measuring anxiety as a treatment endpoint in youth with autism spectrum disorder. J Autism Dev Disord, 44: 1128-1143.

- Wolery M, Garfinkle AN (2002) Measures in intervention research with young children who have autism. J Autism Dev Disord 32: 463-478.

Open Access Journals

- Aquaculture & Veterinary Science

- Chemistry & Chemical Sciences

- Clinical Sciences

- Engineering

- General Science

- Genetics & Molecular Biology

- Health Care & Nursing

- Immunology & Microbiology

- Materials Science

- Mathematics & Physics

- Medical Sciences

- Neurology & Psychiatry

- Oncology & Cancer Science

- Pharmaceutical Sciences