Screening for Social and Emotional Delays in Young Children Who Live in Poverty: A Brazilian Example

Luis Anunciação*, Chen Chieh-Yu, Jane Squires and Landeira-Fernandez J

DOI10.4172/2472-1786.100068

Luis Anunciação1*, Chen Chieh-Yu2, Jane Squires3 and Landeira- Fernandez J1

1Department of Psychology, Pontificia Universidade Catolica do Rio de Janeiro, Brazil

2Department of Special Education, National Taipei University of Education, Taiwan

3Department of Special Education and Clinical Sciences, University of Oregon Eugene, USA

- *Corresponding Author:

- Luis Anunciação

Doctorate in Psychology

Pontificia Universidade Catolica do Rio de Janeiro

(PUC-Rio), Brazil

E-mail: luisfca@gmail.com

Received Date: February 20, 2018; Accepted Date: April 03, 2018; Published Date: April 10, 2018

Citation: Anunciação L, Chieh-Yu C, Squires J, Landeira-Fernandez J (2018) Screening for Social and Emotional Delays in Young Children Who Live in Poverty: A Brazilian Example. J Child Dev Disord. 4:5. doi: 10.4172/2472-1786.100068

Abstract

Emotional and social competence are notable predictors of future mental health outcomes. Studies have shown that poverty can negatively affect a child’s development in several ways. In the Brazilian educational system, no direct payment is required to enroll children in public daycare centers. However, many daycare centers are in impoverished urban areas where the rates of violation of children’s rights are still high. This situation is concerning because of the possible impact on children’s development. The aim of this work was to investigate latent growth in 6,530 three- to four-year-old children who were enrolled in public daycare centers in the city of Rio de Janeiro in 2011 and 2012. We used a modified version of the Ages and Stages Questionnaire: Social and Emotional (ASQ:SE), in which 21 items across the questionnaires were retained. Latent Growth Modeling was performed by constraining intercepts of the repeated measures to zero, and the slope’s loadings corresponded to the study’s time scale (in our case, 0 for age 3 and 1 for age 4). The intercept and slope results were significant (p<0.001) and positive, indicating variability in the individuals’ starting points. Consistent with these results, the scores increased as the children got older. Our findings suggest that children who are enrolled in Brazilian public daycare centers are achieving the expected emotional or social milestones that are appropriate for their age.

Keywords

Child development; Longitudinal research; Latent growth modeling; Ages and stages questionnaires; Daycare centers; Psychometrics

Introduction

Social and emotional domains are important predictors of mental health and the development of cognitive abilities and executive functions, including attention, working memory, and inhibitory control. Research suggests that deficits in emotion regulation and social competence are linked to greater levels of behavioral problems, difficulties with peers, and later psychopathology [1,2]. The development of both emotion regulation and social competence are also related to environmental characteristics [3].

In this direction, there is a vast international literature on the nature and extent of child poverty and a growing body of evidence on the consequences of child poverty: children who grow up in low-income environments face considerable barriers to healthy development and are more likely to be exposed to multiple environmental hazards, such as violence, crime, and drug abuse [4]. Low-income parents are often overwhelmed by reduced self-esteem, depression, and a sense of powerlessness and incapacity to cope—feelings that can get passed along to their children in the form of insufficient nurturing, negativity, and an overall failure to focus on children's needs [3].

In Brazil, a governmental program began in 2010-2012 to assess the development of children who were enrolled in public daycare centers, and during 2011 and 2012, emotional and social aspects of child development were also assessed [5]. In public daycare centers, because no direct payment is required, mostly children come from low-income/very poor families. This program was highly influenced by evidence from the United States, where evaluations of early childhood education programs demonstrated long-term impacts on a wide range of outcomes, including scholastic achievement, poverty, and criminal behavior.

The Brazilian program was unfortunately stopped in 2013, and few results are known about its outcomes [5]. That said, the present study focuses on describing and discussing child development based on the results that were obtained during this period.

Material and Methods

The participants included a total of 6,530 children (52% boys and 48% girls) who were enrolled in 357 different daycare centers in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. They were assessed by caregivers or teachers across 2 years (2011, when they were 3 years old; 2012, when they were 4 years old) using the Brazilian version of the Ages and Stages Questionnaires: Social and Emotional (ASQ:SE) [2]. More information about this procedure can be found in other publications [3].

We used 21 items across both 36- and 48-month ASQ:SE intervals to accommodate the ages of our preschool population. In the ASQ:SE traditional scoring system, higher scores indicate a risk for emotional and social problems. In this study, the system was reversed to reflect typical development. Because of that, we coded with “2” when participant checked the column of “Often or Always” for positive items or “Rarely or Never” for problematic items; “1”, when the column “Sometimes” was checked; “0” when participant checked the column of “Rarely or Never” for positive items or “Often or Always” for problematic items (Table 1).

| Domain | Content | Item (3 years) |

Item (4 years) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Emotional | Child moves from one activity to the next | 8 | 20 |

| Child settles down after exciting activity | 7 | 7 | |

| Child hurts self on purpose | 22 | 23 | |

| Child does what you ask | 11 | 13 | |

| Child cries, screams, or has tantrums for long periods | 19 | 8 | |

| Child tries to hurt other children | 29 | 31 | |

| Child calms down within 15 minutes | 5 | 4 | |

| Child destroys or damage things on purpose | 24 | 25 | |

| Child seems more active than other children of his/her age | 12 | 16 | |

| Child does things over and over and can’t seem to stop | 21 | 22 | |

| Child sleeps at least 8 hours in a 24-hour period | 16 | 15 | |

| Child stays away from dangerous things | 23 | 26 | |

| Social | Child can name a friend | 26 | 27 |

| Child uses words to tell you what he/she wants | 17 | 17 | |

| Child uses words to describe his/her feelings | 25 | 19 | |

| Child plays/talk with adults he/she knows well | 3 | 3 | |

| Child is interested in things around her (people, toys) | 10 | 9 | |

| Child likes to play with other children | 28 | 30 | |

| Child looks at you when you talk | 1 | 1 | |

| Child seems happy | 9 | 14 | |

| Child likes to be hugged or cuddled | 2 | 5 |

Table 1: Twenty-one item ASQ:SE.

Ethical approval for this study was granted by the Ethical Committee of the Pontifical Catholic University of Rio de Janeiro. The data were analyzed using R 3.4 [6] and MPLUS V.8 [7] software.

Results and Discussion

To be able to describe and compare the results that were obtained with the ASQ:SE across time points and to avoid potential interpretation bias, we checked whether both versions that were used were statistically equivalent. We explored measurement invariance by verifying differences in practical fits, such as Confirmatory Fit Index (CFI) and Tucker Lewis Index (TLI) instead of checking a non-significant p value. According to the standard approach, the more constrained model is preferred only when the χ2 test results in a nonsignificant p value (p ≥ 0.05). The χ2 value is inflated, however, when using large sample sizes [8] (Table 2).

| df | χ2 | Δχ2 | χ2 df | p | CFI | RMSEA | ΔCFI | ΔRMSEA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Configural | 376 | 6136 | .923 | .048 | NA | NA | |||

| Loadings | 395 | 6439.8 | 104.295 | 19 | < .001 | .926 | .046 | .003 | .002 |

| Intercepts | 414 | 6446.5 | 30.949 | 19 | .04 | .924 | .046 | .003 | 0 |

| Means | 416 | 6882.2 | 312.256 | 2 | < .01 | .918 | .047 | .005 | .001 |

Table 2: Fit indices of measurement invariance.

As shown in Table 2, the results indicated longitudinal measurement equivalence. To assess changes in behavior as a function of the children’s age, we performed Latent Growth Modeling. Once factor loadings, thresholds, and variances were constrained across time (in our case, 0 for age 3 and 1 for age 4). Recent studies have shown that this approach is well suited to remove the effects of measurement error that might exist in predictors or outcomes [9].

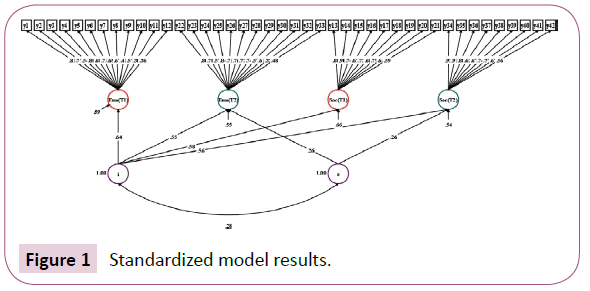

The paths coefficients from both domains were: slope with intercept =0.035, p=0.019; slope mean =0.384, p<0.01; intercept variance =0.267, p<0.01, slope variance =0.059, p<0.01, (Figure 1 presents the standardized results). Once the difference between the two-time points was significant, we decided to report raw scores to facilitate understanding of the results and to compute the CoheÃÆââ¬Â¡Ãâùs d effect size (Table 3).

| Female (n = 3,095) | Male (n = 3,435) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| M (SD) | M (SD) | Effect size | ||

| Emotional | 3 years | 21.4 (2.92) | 20.5 (3.51) | 0.28 |

| 4 years | 22.3 (2.44) | 21.4 (3.27) | 0.31 | |

| Effect size | 0.33 | 0.27 | ||

| Social | 3 years | 16.8 (2.07) | 16.4 (2.44) | 0.18 |

| 4 years | 17.3 (1.59) | 17 (1.95) | 0.17 | |

| Effect size | 0.27 | 0.27 | ||

| Total | 3 years | 38.2 (3.9) | 36.9 (4.68) | 0.30 |

| 4 years | 39.7 (3.18) | 38.4 (4.25) | 0.35 | |

| Effect size | 0.42 | 0.34 |

Table 3: Descriptive results and effect size (Cohen’s d).

All scores increased as the children got older. Females tended to have higher scores on all domains of the ASQ:SE. If we assumed that higher scores were associated with lower developmental risk for later social and emotional difficulty, then our findings are consistent with the literature [1,2].

Other studies have shown that girls are, on average, more socially competent than boys. Externalizing behaviors (e.g., hyperactivity) are more common among boys than among girls. One explanation for this might lie in the fact that boys are more physically active, engage in more risk-taking behavior and rough-and-tumble play, and exhibit more anger and aggression toward peers than girls [10]. When adults, the odds of having a psychological condition are higher in women [11].

Conclusion

The purpose of present study was to describe and discuss child development using data gathered with Brazilian children enrolled in public daycare centers. We used a longitudinal version of ASQ:SE with 21 items across both 36 and 48-month and assessed the changes in behavior using a Latent Growth Modeling.

Two important features in our study are

1. the items used on ASQ:SE and

2. the social conditions of the Brazilian public daycares, where data were gathered.

First, since the items were the same, we could check the children’s latent growth. Second, mostly of these children are growing up in low-income families, and because poverty is not exclusive to developing countries, our results can be useful for shedding light on child development in a challenging environment.

In our results, the intercept and slope variances were significant and positive, indicating variability in the individuals’ starting points. In the same direction, the raw scores increased as the children got older. Our findings suggest that children who are enrolled in Brazilian public daycare centers are achieving the expected emotional or social milestones that are appropriate for their age. Despite growing up in low income households, these children appear to be gaining social and emotional competence and performing well in their preschool environments.

Although there are some limitations (e.g., observational design with no control group), we believe that these results can be generalized to similar populations who live in poverty. In similar direction, as long the evaluation of the quality of early care and education is part of political agenda and expand the current understanding of public services, this study is also relevant [4].

Longitudinal studies have long played a critically important role in developmental psychology and pediatric medicine, and these designs are becoming increasingly relevant to contemporary research. If researchers are able to estimate intra-individual patterns of changes over time, then they may better understand developmental trajectories of children and improve outcomes through early and targeted intervention.

Finally, we all agree that other studies are necessary to further document our findings, to address new questions about child development and to nurture an ‘evidence-based policy-making’ scenario using of statistics and statistical thinking throughout government decisions. Currently, new studies are being conducted to explore these issues.

References

- Blandon AY, Calkins SD, Keane SP (2010) Predicting emotional and social competence during early childhood from toddler risk and maternal behavior. Dev Psychopathol 22: 119-132.

- Kalvin CB, Bierman KL, Gatzke-Kopp LM (2016) Emotional reactivity, behavior problems, and social adjustment at school entry in a high-risk sample. J Abnorm Child Psychol 44: 1527-1541.

- Gupta RP, de Wit ML, McKeown D (2007) The impact of poverty on the current and future health status of children. Paediatr Child Health 12: 667-672.

- Ceglowski D, Bacigalupa C (2002) Four perspectives on child care quality. Early Child Educ J 30: 87-92.

- Anunciacao L, Squires J, Landeira-Fernandez J (2018) A longitudinal study of child development in children enrolled in Brazilian public daycare centers. Glob J Educ Stud 4: 31.

- R Development Core Team (2011) R: a language and environment for statistical computing. R Found Stat Comput Vienna Austria.

- Muthén L, Muthén B (2017) Mplus user’s guide (8th Edn). Los Angeles, p: 856.

- Widaman KF, Ferrer E, Conger RD (2010) Factorial invariance within longitudinal structural equation models: measuring the same construct across time. Child Dev Perspect 4: 10-18.

- Curran PJ, Obeidat K, Losardo D (2010) Twelve frequently asked questions about growth curve modeling. J Cogn Dev 11: 121-136.

- Vahedi S, Farrokhi F, Farajian F (2012) Social competence and behavior problems in preschool children. Iran J Psychiatry 7: 126-134.

- Riecher-Rössler A (2017) Sex and gender differences in mental disorders. Lancet Psychiatry 4: 8-9.

Open Access Journals

- Aquaculture & Veterinary Science

- Chemistry & Chemical Sciences

- Clinical Sciences

- Engineering

- General Science

- Genetics & Molecular Biology

- Health Care & Nursing

- Immunology & Microbiology

- Materials Science

- Mathematics & Physics

- Medical Sciences

- Neurology & Psychiatry

- Oncology & Cancer Science

- Pharmaceutical Sciences