Representations of Families through the ChildrenÃÆâÃâââ¬Ãâââ¢s Drawings in Parental Divorce Incidents in Greece

Giotsa A and Mitrogiorgou E

DOI10.4172/2472-1786.100037

Department of Early Childhood Education, University of Ioannina, Greece

- *Corresponding Author:

- Artemis Giotsa

Associate Professor of Social Psychology

Department of Early Childhood Education

Faculty of Education, University of Ioannina,Greece

Tel: +30 26510 05767

E-mail: agiotsa@uoi.gr

Received date: July 14, 2016; Accepted date: September 26, 2016; Published date: September 30,2016

Citation: Giotsa A, Mitrogiorgou E. Representations of Families through the Children’s Drawings in Parental Divorce Incidents in Greece. J Child Dev Disord. 2016, 2:29 doi: 10.4172/2472-1786.100037

Abstract

The purpose of the present research is the study of children’s perceptions through their drawings about their divorced families. Specifically the study is focused on the roles and functions in the family and the dynamics between the family members. Concerning the sample, it is consisted of 26 children’s drawings. The participants are aged between 5 and 12 years old (M=8.23, SD=2.42) and all of them are living with the mother. It is important to say that the present research was conducted when the parents were already divorced for six months or less. The psychometric tools which were given to each child were two kinds of drawings: (1) Corman’s static family drawing and (2) Burns & Kaufman’s kinetic family drawing.

As for the results of the present study, it is shown that the 38.5% of the participants chose to draw their real family in the static family drawing, including though both parents, another 38.5% drew an imaginary family and the 23% drew an ideal family (relatives or friends). Concerning the kinetic family drawings, the 69.2% of the participants drew both parents. However the 30.8% is shown to interact with none of the parents or other familial members and also the self-figure is drawn isolated, without being a part of any subsystem, in the majority (61.5%) of the kinetic family drawings. Concluding, based on the fact that the drawings consist a projective assessment technique, they are able to show the children’s thoughts, emotions or desires. As a result, we can assume that the children do not seem to accept the recent parental separation, as the majority of the participants drew both parents. Nevertheless, there is a noteworthy percentage of drawings, where the participants’ self-figure interacts with no other person or tends to be totally isolated.

Keywords

Family representations; Family roles; Family functions; Children’s drawings; Parental divorce

Introduction

Parental divorce and its impact on children

Parental divorce has been assessed by many researchers [1-4] as a stressful incident for not only the couple, but also the children. The stress provoked to children could mostly result from the changes which happen in children’s way of living. For example, they are obliged to get used to a different household, as one of the parents tends to move out after the divorce. Also children often may have to move to a different house or neighborhood, change school or habits.

The stress provoked to children, during a parental divorce incident, is often connected with difficulties in social level [5-6], emotional level [7-9], behavioral level [10,11] or even academic level [8- 10,12,13].

More specifically, concerning social difficulties, Felner and colleagues [5] support that children coming from divorced families are more frequently aggressive or even delinquent. As for emotional distress, some researchers [7,9] discuss about problematic relationships among children coming from divorced families and their peers. Additionally there are authors who focus on the behavioral problems [14-16]. These authors support that children coming from families with closely related parents tend to exhibit fewer behavioral problems and greater psychological adjustment than children coming from families with divorced or remarried parents. Last Fomby and Cherlin [8] and Nielsen [17] indicate that a stressful parental separation can result to academic difficulties for the children or reduced academic achievement.

On the other hand, there is data [18-20] suggesting that even in parental separation cases the parental attitude and support towards their children can enhance the well-being of them. Focusing mostly on the maternal role, there is data [21,22] indicating the importance of a stable maternal figure in children’s life, in parental divorce incidents. Additionally there is also evidence supporting the benefits coming from the qualitative father’s presence in their children’s life, even if the father is no longer part of the same household as them [23-25].

Argyrakouli, Booth and Amato, Herlofson [26-28] conducted researches taking under consideration the gender of parents and children in parental divorce incidents. They found that the resilience of the relationship between each parent and the son or the daughter can be correlated to the parent’s and child’s genders. More specifically the relationship between mother and daughter and the relationship between father and son seemed to be the most resilient. In contrary the relationship between the mother and the son or the father and the daughter tend to suffer more.

Last but not least there is evidence connecting the parental divorce with long-term effects on children. Kalmijn [29] supports that the relationship between parent and child is able to influence the children’s relationships when they become adults. More specifically the communication between parents and children seems to be very meaningful for the opinion formed by children about their young and adult life. The longer the parents were together with their child in childhood, the more positive adult the child becomes. Children are able to perceive feelings of hostility and neglect among the parents. Gottman and colleagues’ researches [30,31] indicate that this kind of feelings among the parents can be connected with children’s violent behavior towards their peers, observed when they are young (e.g. in school) or even in their adult life (e.g. in their own marriage).

Parental divorce in Greek family

A quite large amount of research has been conducted also in Greece, concerning the parental divorce’s consequences on the family context. The Greek evidence tends to mostly agree with the international literature. More specifically it is shown [32-34] that it is more likely for children coming from divorced families to come up with behavioral problems than children coming from nuclear families. However Manolitsis and Tafa [35] argue that gender and age have also to do with these behavioral problems upon entering the new single-parent household. Preschool children and adolescents tend to develop more problematic behaviors than children in childhood. Also girls show lower rates of behavioral distress than boys.

In addition it is obvious [32] that children living in single-parent households develop lower school performance than children coming from nuclear families. Their teachers often tend to characterize them as “average” students [33]. On the other hand, single parents themselves often support that single parenthood is not able to influence to such an extent the school performance of their children [36].

Other researchers focus on the relationship between the two parents after the divorce, supporting that a satisfactory communication between them is crucial and it may even lead to the maintenance of a good relationship between the child and the absent parent [37]. In Greece the single-parent family resulting from parental divorce is very often supported from the single parent’s siblings, parents, extended family members and friends [38]. For example, grandparents, uncles and aunts usually provide a supporting context, assisting the single parent and the children. The important role of the wider family in Greece is indicated by other researchers too [39-42].

Family drawing

Family drawing is a very useful instrument in order to study children’s perceptions about the relationships between the family members. Appel [43] and Wolff [44] were the first authors who characterized family drawings as projective tests. Later Hulse [45] and Porot [46] conducted the first systematic studies using family drawings, asking from the participants to draw their “real” families. Indicatively, some more family drawings used in studies were the the “family in animals” [47], “static family drawing” [48,49], “kinetic family drawing” [50-52], “enchanted family drawing” [53], “Family-System-Test” or FAST [54].

Projective techniques usually provide open-ended instructions (e.g. “Draw a family” or “Draw your family”) and they permit participants flexibility in the nature and the number of their responds [55]. As a result, even during a crisis in the family context, such as parental divorce, children can respond about their families through projective techniques, according to Lilienfeld and colleagues [55]. The present research is based on the instruments developed by Corman [48,49] and Burns and Kaufman [50-52] and the researches that they conducted using projective family drawings.

Corman developed the static family drawing [48,49], providing to his respondents the open-ended instruction “Draw a family”. This family drawing type is called static because the family appears to be standing and not acting [56]. Based on the researches he conducted, Corman indicated that static family drawing gives children the opportunity to be less reluctant and more complaisant to project in their drawings their real emotions for each family member. Hence they can draw their real families, an imaginary family or an ideal family. Additionally comparing to other family drawings, such as Porot’s “Draw your family” test [46], it is less possible for the respondents to try to consciously control the drawing process, due to guilt or second thoughts. There are various researchers who used the static family drawing with pre-school or school-aged children, due to its characteristics [37,57,58].

Burns and Kaufman developed the kinetic family drawing [50- 52], providing to their respondents the instruction “Draw your family acting. Draw all the members of your family doing something”. This family drawing kind is called kinetic, because the respondents must include action in their drawings. Burns and Kaufman tended to interpret the data they collected, developing gradually a catalogue of interpretations [52]. Other researchers who used this kind of family drawing [41,59-62] either used this catalogue or fleshed it out with more interpretations.

Purpose of the present study The present paper constitutes a part of a wider project which is still in progress and aims at studying perceptions of children about their families within crisis. Parents’ divorce or separation, parent’s recent unemployment status, moving or immigration, a family member’s death are all incidents which it is possible to lead to a period of crisis for the family context, as they all affect the family’s conditions of living. As a result, the interesting part of the present study is the fact that the data was collected, while the families of the children who participated were in crisis. Precisely the parents of the children of the sample were divorced or separated for six months or less, when the data was collected.

It becomes obvious, through the literature review, that although there is a range of data about the parental divorce in Greece, there is a gap concerning the first months after the parents’ separation or divorce and especially through children’s projective techniques. Consequently, focusing on the divorced or separated families, this paper aims at studying children’s viewpoints of their families within the crisis caused by parental divorce, expressed through their drawings. Another aim of this paper is to enlighten the family system dynamics existing in families dealing with parental divorce. The family system dynamics are also observed through the children’s point of view, collecting information by their drawings. According to these aims, we expect that the respondents’ potential stressful feelings will be observed through their drawings. Also we expect that the sample’s children will be shown to interact and have a strong bond with the parent they are living with, after the divorce. Last the wider family’s members, beyond the parents and the siblings, will be present in the sample’s drawings, indicating their supportive role in the life of the sample’s respondents.

Methodology

Sample of the present study

The sample used in this paper was recruited in cooperation with the parents’ associations in the schools of the wider region of Epirus in Greece. Through the parents’ associations, 13 children were finally chosen whose the parents were either divorced or separated for six months or less in that time.

Specifically, the sample consists of 26 drawings, which were made by 13 children. The sample’s respondents were aged between 5 and 12 years old (M=8.23, SD=2.42). The majority of the sample was female (84.6%) and the minority was male (15.4%). All participants (100%), as well as both parents of each family are Greek. Also it is very important to clarify that almost half of the sample’s participants (53.8%) have one or two siblings, while the other half (46.1%) are only-children. Also all (100%) the children of the sample and their siblings (in case they have any) are living with their mothers in the present day.

Procedure and instrumentation

The present research is characterized as qualitative, due to the projective drawing techniques and the analysis method we used. According to Elliott [63,64], researchers who use quantitative methods usually test hypothesized relationships and causal explanations, assess the reliability, the validity and the factor structure of psychometric measurements and assess the generalizability level across samples. In contrary, qualitative researches, as the one presented here, aim to understand the respondents’ perspective, while they encounter, engage and live through several situations [65]. Accepting the impossible of representing the participants’ own perspectives totally (and without claiming to), we used the drawings, which allow flexible responses by the participants, and we aim to understand as adequately as possible their experience, thoughts and actions and to provide meaningful answers to the questions posed in the first place.

Each participant had to respond to both the instruments used in this study, the static and the kinetic family drawing. The respondents were tested anonymously and individually and after their parents gave their informed consent for them to participate in the research. As the researchers cooperated with the parents’ associations in each school, the testing procedure took place in the participants’ schools, after the end of the lessons, as the school is a place familiar to the children. After each drawing process, a conversation followed between each respondent and the researcher. The duration was approximately one hour for each participant.

More precisely the whole procedure was divided into three parts for each instrument. At first the respondents were tested on the static family drawing. After completing all the three parts of the procedure for this kind of drawing, they proceeded to the kinetic family drawing. The procedure is fully described through the following three parts:

The drawing creation part: During this first part, the researcher chose the appropriate place and time. The researcher also provided the respondent with instructions, concerning the process. As for the static family drawing, the instruction was “Draw a family”. During, the drawing creation the researcher did not interfere at all, even if he was asked. He observed though the participant’s writing direction, the row of the drawn figures, the way the participant chose in order to correct or modify something in the drawing.

As for the kinetic family drawing, the instruction was “Draw your family acting. Draw all the members of your family doing something”. The researcher clarified to the participants that they had to draw their own families. During the drawing process, he was again only an observer.

The communication part: The second part included a conversation between the researcher and each participant individually. At first the participant described the drawing and talked about it. Then he/ she answered some questions, posed by the researcher.

As for the static family drawing, the conversation was based on the questions proposed by Cambier and Pham Hoang Quoc Vu [65]:

• Who are they? Where are they? Could you tell a story about these persons you drew?

• Which person is the best and why?

• Which person is the least good and why?

• Which person is the happiest and why?

• Which person is the least happy and why?

• Which is your favorite person? Why?

• If you were a member of this family, which person would you choose to be? Why?

However the researcher could ask for more details, if it was necessary.

As for the kinetic family drawing, the conversation was semistructured, as the researcher was able to choose some of the proposed questions, to modify them, to consider the participant’s answers, age and background (class in school, siblings, the parent with whom the participants live after the separation or divorce), to focus on some of the questions and ask for more details [61]. The questions used in this part of the present study are a combination of the questions suggested by Burns and Kaufman [50-52] and the modifications and additions by Mylonakou-Keke [60,61]. More specifically, some of the questions used in the present study were the following:

• Questions about each figure separately, such as (indicatively):

ÃÆâÃâââ¬âÃâêÃÆâÃâââ¬âÃâê What is this person’s name? In what way are you related to this person?

ÃÆâÃâââ¬âÃâêÃÆâÃâââ¬âÃâê What is this person doing here, in your drawing? What do you think he/she could have done before that? What do you think he/she might do after that?

ÃÆâÃâââ¬âÃâêÃÆâÃâââ¬âÃâê What could this person have in mind? How could this person feel?

• Questions concerning the respondent, such as (indicatively):

ÃÆâÃâââ¬âÃâêÃÆâÃâââ¬âÃâê If you had the chance to change something in this family, what did you choose?

ÃÆâÃâââ¬âÃâêÃÆâÃâââ¬âÃâê Looking at your drawing, do you feel calm or tension?

• General questions, such as (indicatively):

ÃÆâÃâââ¬âÃâê Who is looking to whom?

The drawing processing part: During the last part of the procedure, the researcher processed the collected data. As for the static family drawing, we were based on the analysis suggested by Karella [56], who organized an explanatory list. This list includes interpretations concerning the way the figures are drawn (for example the body parts, the head, the eyes etc.).

As for the kinetic family drawing, we utilized the interpretative manual developed by Burns and Kaufman [52] and the analysis steps suggested by Mylonakou-Keke [61]. As a result, we observed every drawing, focusing on the graphics, each figure’s size and place, the kind of action chosen for the drawn persons, the interaction among the drawn persons and the “barriers” placed between figures.

In the present paper, we focused also on the participants’ responds (during the communication part) and we used them in addition to the drawings’ analysis (during the drawing process part). Consequently, we were able to create an opinion as integrated as possible.

Results

Static family drawings

Static family drawings [48,49] give children the chance to be more spontaneous and less reluctant, when they have to respond about family. As a consequence, it is more possible that they project their real feelings and thoughts. Respondents are also free to choose among their own family, an imaginary family and an ideal family to draw in a static family drawing.

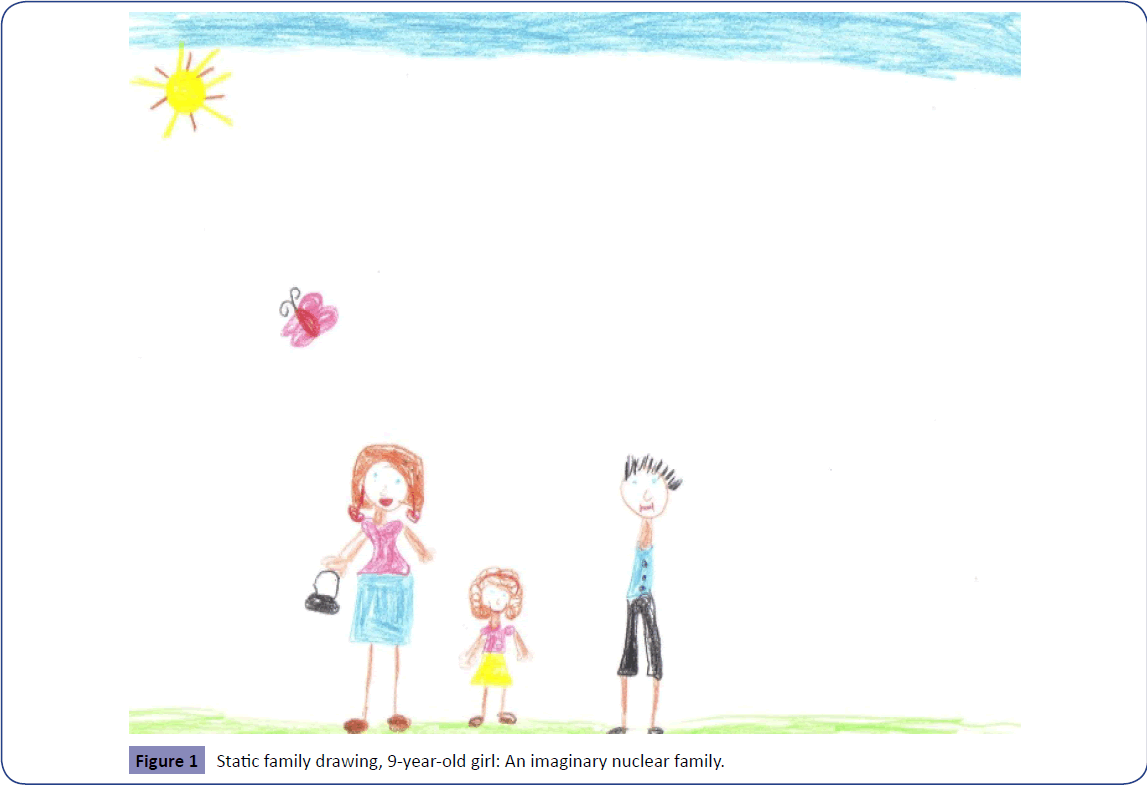

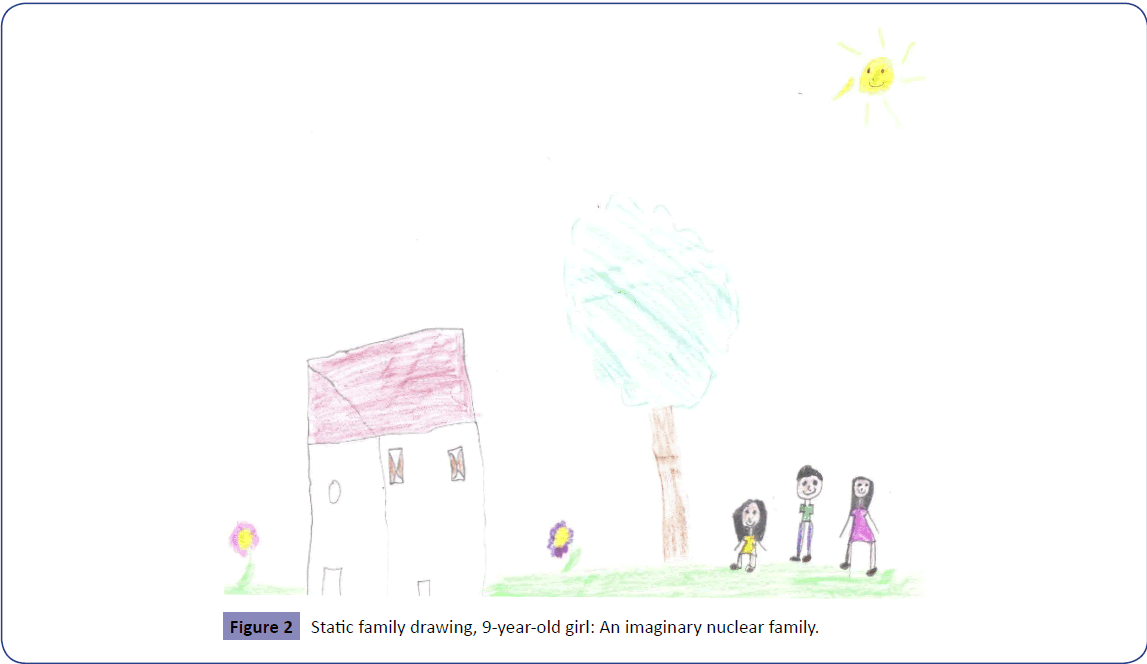

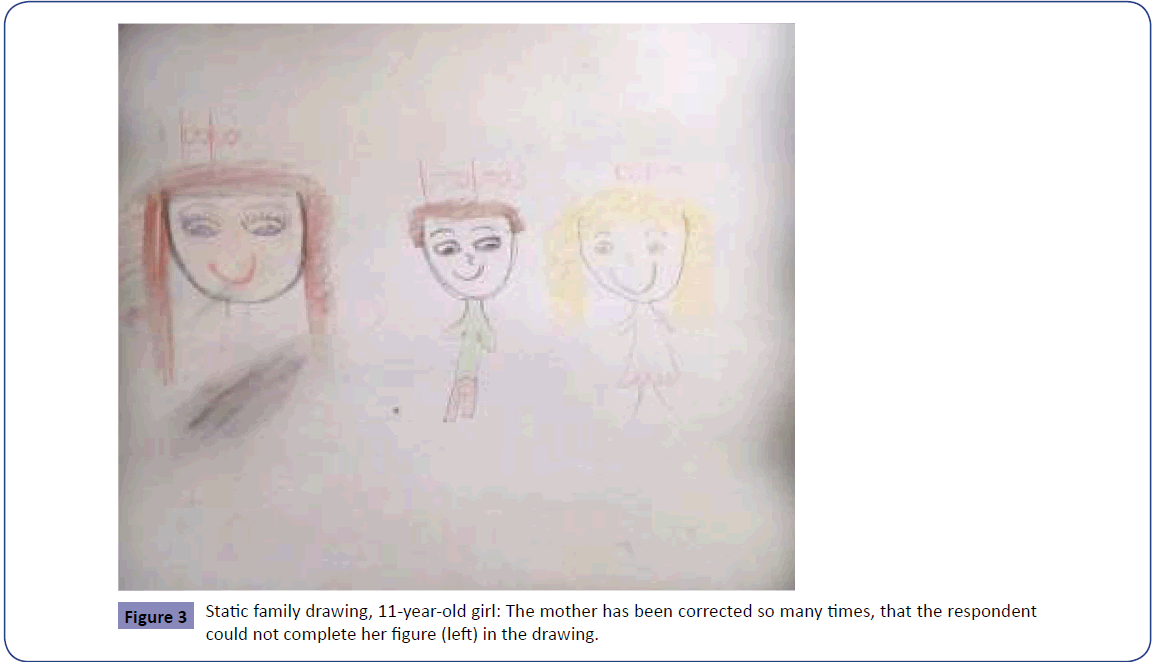

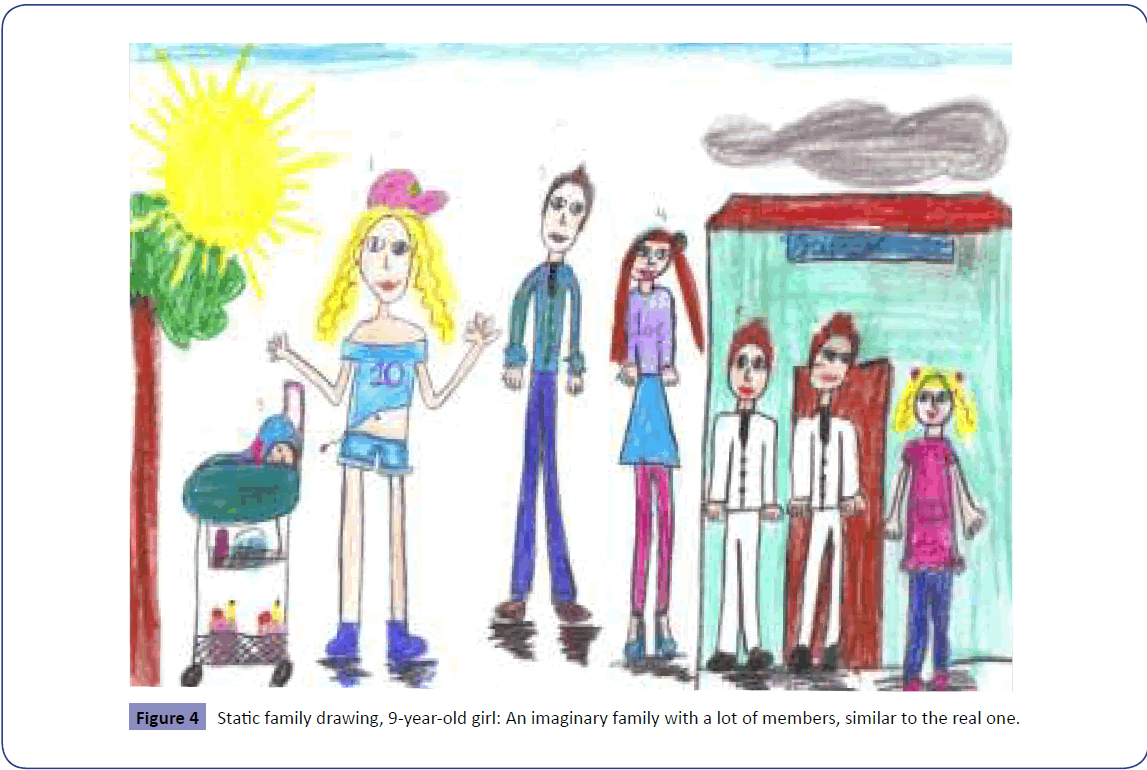

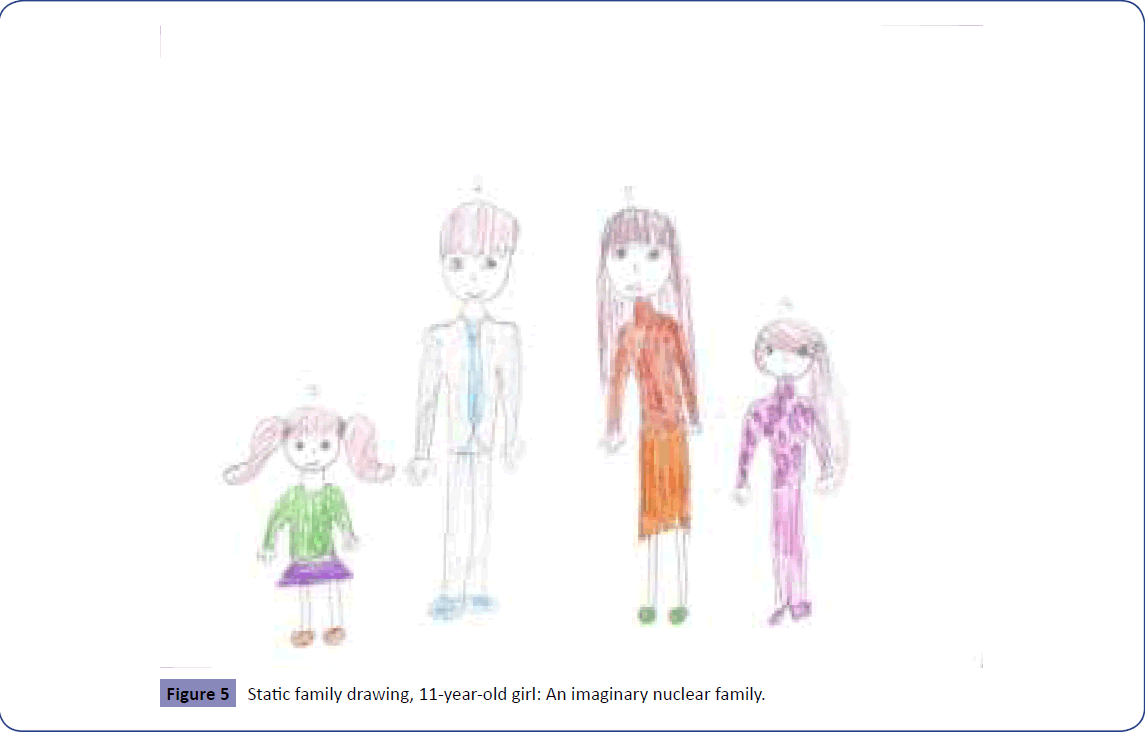

As for the present study’s respondents (Table 1), the majority (61.5%) chose to draw either an imaginary (38.5%) or an ideal family (23%). More specifically, the children who drew an imaginary family (Figures 1-5) were older children, aged between 9 and 11 years old. The age can influence the choice of the family kind, when the children are tested on the static drawing, as the younger children usually are not able to come up with an imaginary family. It is also interesting the fact that all the drawn imaginary families are nuclear.

| Variables | Percentage | Figures | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Participants’ gender | Male | 15.4% | 5, 6, 9, 10 |

| Female | 84.6% | 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26 | |

| Measurements | Static Family Drawing (SFD) | 50% | 1, 3, 5, 7, 9, 11, 13, 15, 17, 19, 21, 23, 25 |

| Kinetic Family Drawing (KFD) | 50% | 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12, 14, 16, 18, 20, 22, 24, 26 | |

| SFD: Family type | Imaginary | 38.5% | 1, 3, 7, 19, 21 |

| Ideal | 23% | 9, 13, 17 | |

| Real | 38.5% | 5, 11, 15, 23, 25 | |

| SFD, Real family: Parental Figures’ Size | Mother>Father | 60% | 5, 11, 15 |

| Mother=Father | 40% | 23, 25 | |

| KFD: Parental figures included | Both | 69.2% | 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12, 20, 22, 24 |

| Only mother | 23.1% | 14, 16, 18 | |

| None | 7.7% | 26 | |

| KFD: Largest figures | Mother | 46.1% | 4, 10, 14, 16, 22, 24 |

| Mother and Father | 23.1% | 2, 6, 8 | |

| Grandmother | 7.7% | 12 | |

| Other (siblings/equal size/many absent members) | 23.1% | 18, 20, 26 | |

| KFD: Subsystems according to respondents’ interactions with other members | No interaction | 46.1% | 4, 10, 16, 18, 22, 24 |

| With both parents | 15.4% | 8, 12 | |

| Only with mother | 7.7% | 20 | |

| Only with father | 7.7% | 6 | |

| With siblings or relatives | 23.1% | 2, 14, 26 | |

| KFD: Subsystems according to the place of the self-figure and the ‘barriers’ | Isolation | 61.5% | 2, 6, 10, 12, 20, 22, 24, 26 |

| Near both parents | 7.7% | 8 | |

| Near mother | 7.7% | 16 | |

| Near siblings | 7.7% | 14 | |

| Self-figure not included | 15.4% | 4, 18 | |

| KFD, General view: Insecurity, uncertainty, tension | Barely distinguishable figures | 23.1% | 8, 12, 14 |

| Too many corrections during the drawing process | 23.1% | 6, 8, 24 | |

| Squiggly bed | 7.7% | 16 | |

Table 1: Statistics of family drawings.

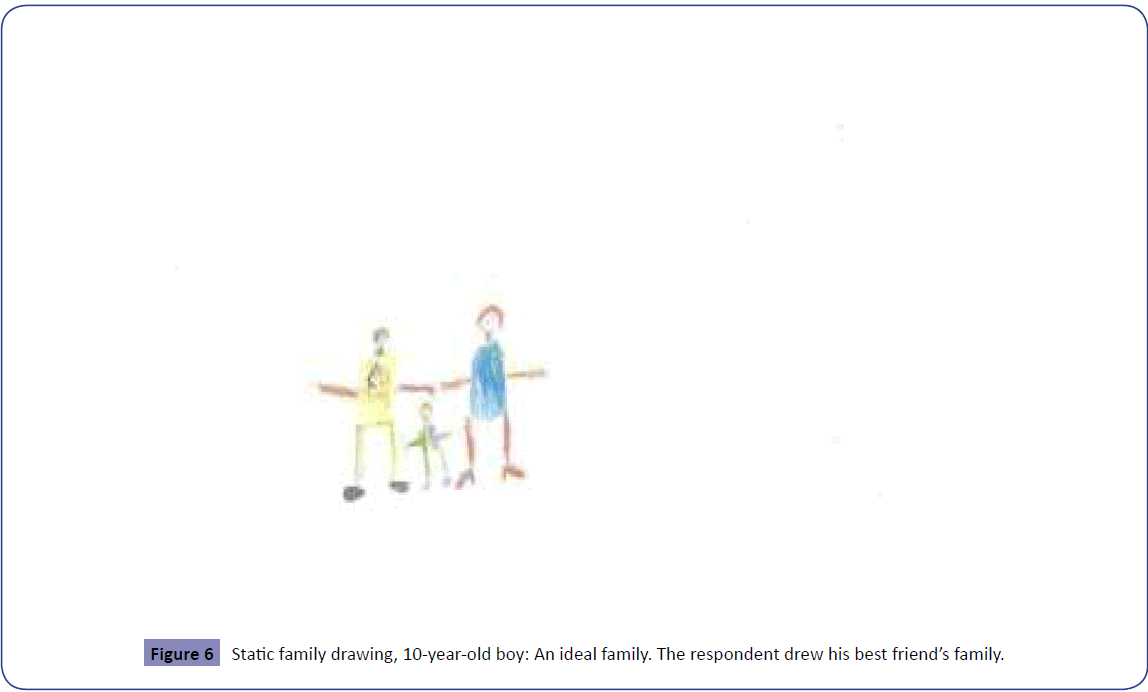

The ideal families shown in the sample’s static drawings (Figures 6-8) are either relatives’ or friends’ families. Only one of the drawn ideal families is nuclear (Figure 6): “This is my best friend’s family”), while the others are consisted of some members of the respondents’ wider families. For example, a 6-year-old girl drew herself and her aunt (Figure 8) and she justified her choice explaining to the researcher that she likes very much her aunt’s home.

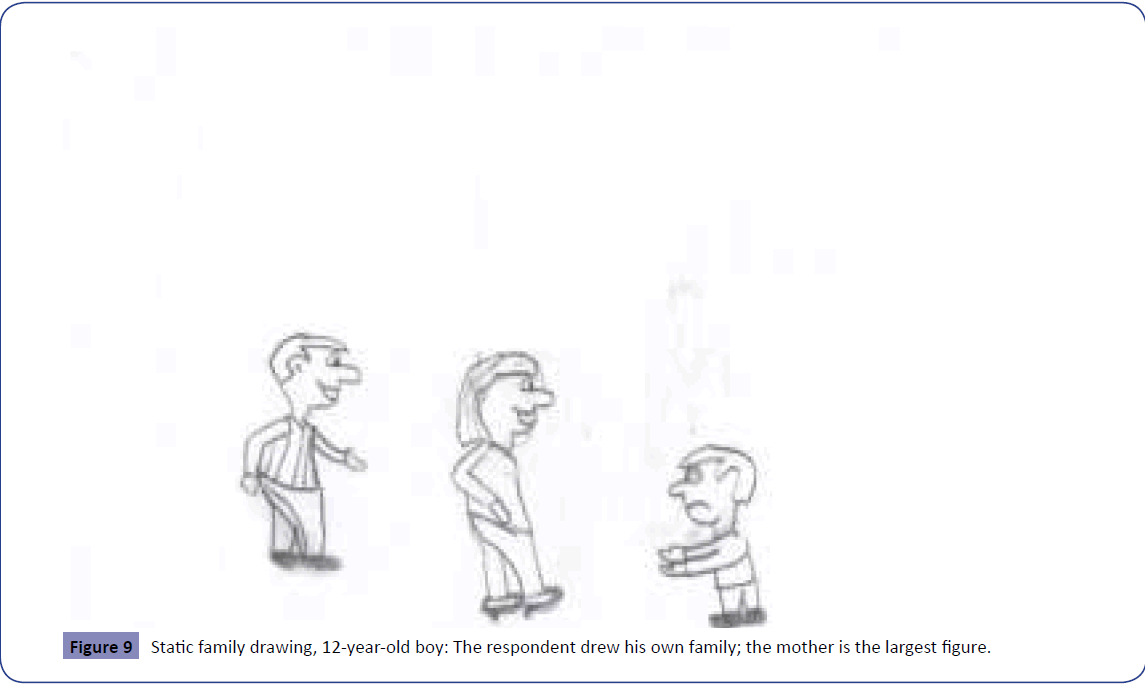

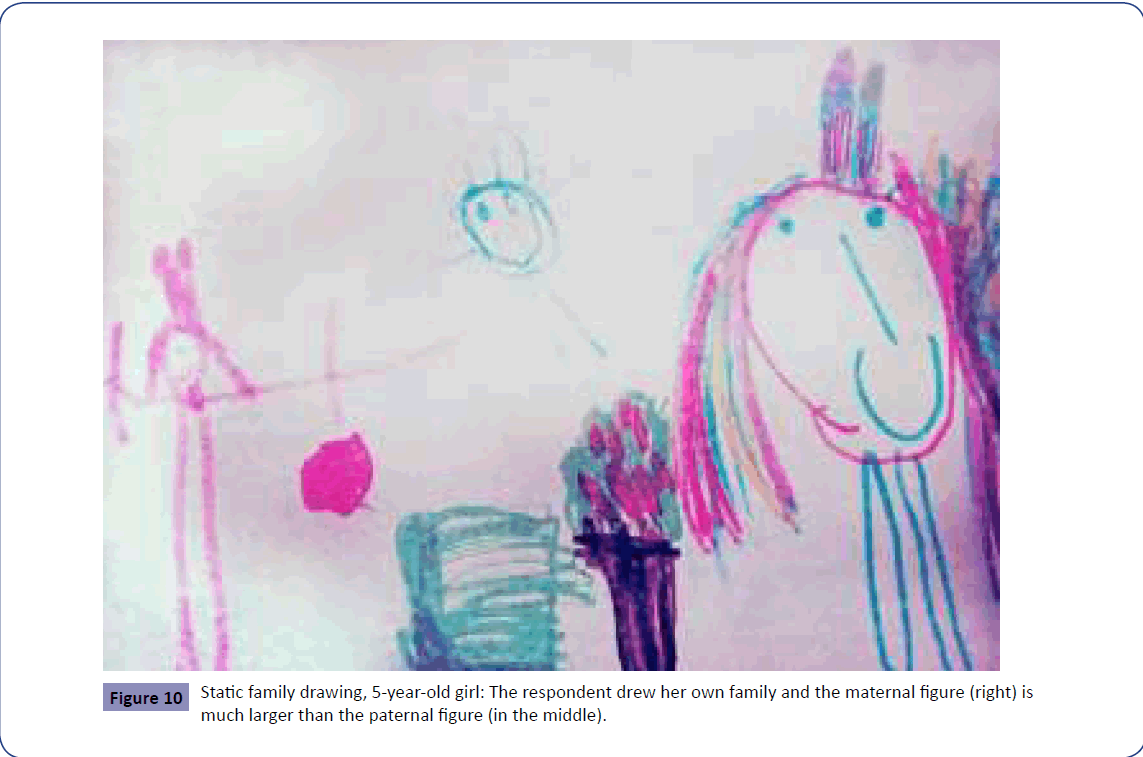

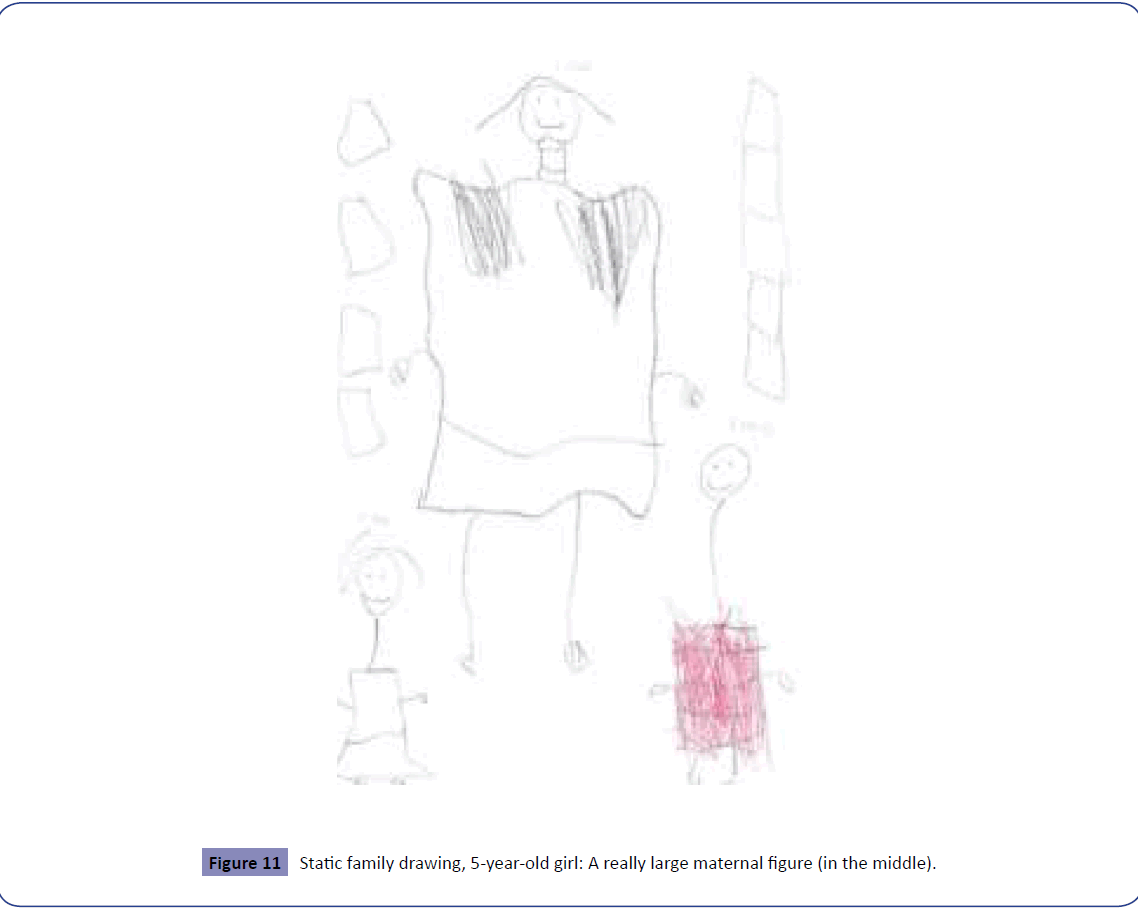

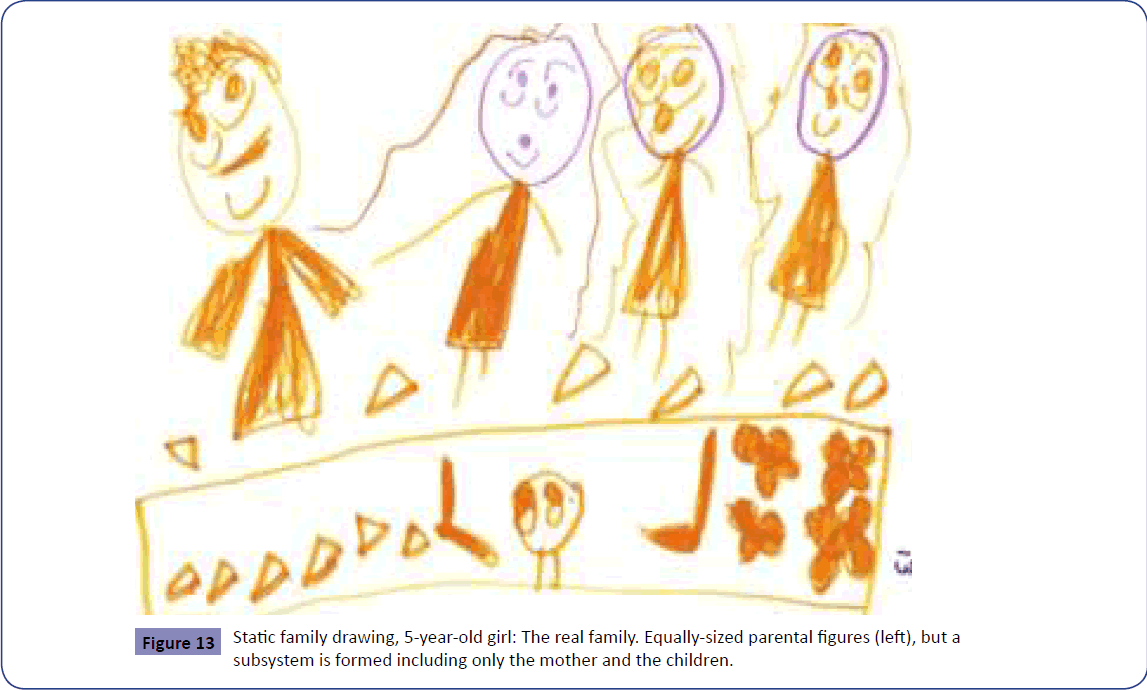

Nevertheless some respondents (38.5%) chose their own families, even if it was not necessary. The drawings (Figures 9-13) showing the real families are very interesting, as all of them represent nuclear families. All the sample’s children drew both parents, even if the fathers are no longer part of their households. We could suggest that these respondents chose their own families, because they are too young to come up with an imaginary family. However their age does not support this suggestion, as they are aged between 5 and 12 years old.

Focusing more on the real families shown in the sample’s static family drawings, we are able to observe that the parental figures are very interestingly sized by the respondent. Even if they include their fathers in the drawings, the paternal figure is not the biggest one in any of these static drawings. In contrary, the paternal figure is either smaller than the maternal (Figures 9-11) or equal to the maternal (Figures 12 and 13). This is a result that could give us an impression of the children’s real emotions towards the parental figures or the important role of the mother in their life, given that all of them are living with her. Last, through the fact that they include both parents in the static drawings, we could assume the children’s inner desire to avoid their households’ changes.

Kinetic family drawings

The kinetic family drawing is more specific than the static, due to the instruction provided to the respondents: “Draw your family acting. Draw all the members of your family doing something” [50- 52]. The kinetic family drawing, combined with the conversation that follows it, can give the researcher a quite clear impression about the respondents’ perceptions about themselves and the others, their family dynamics, the interactions and subsystems within their family systems [66].

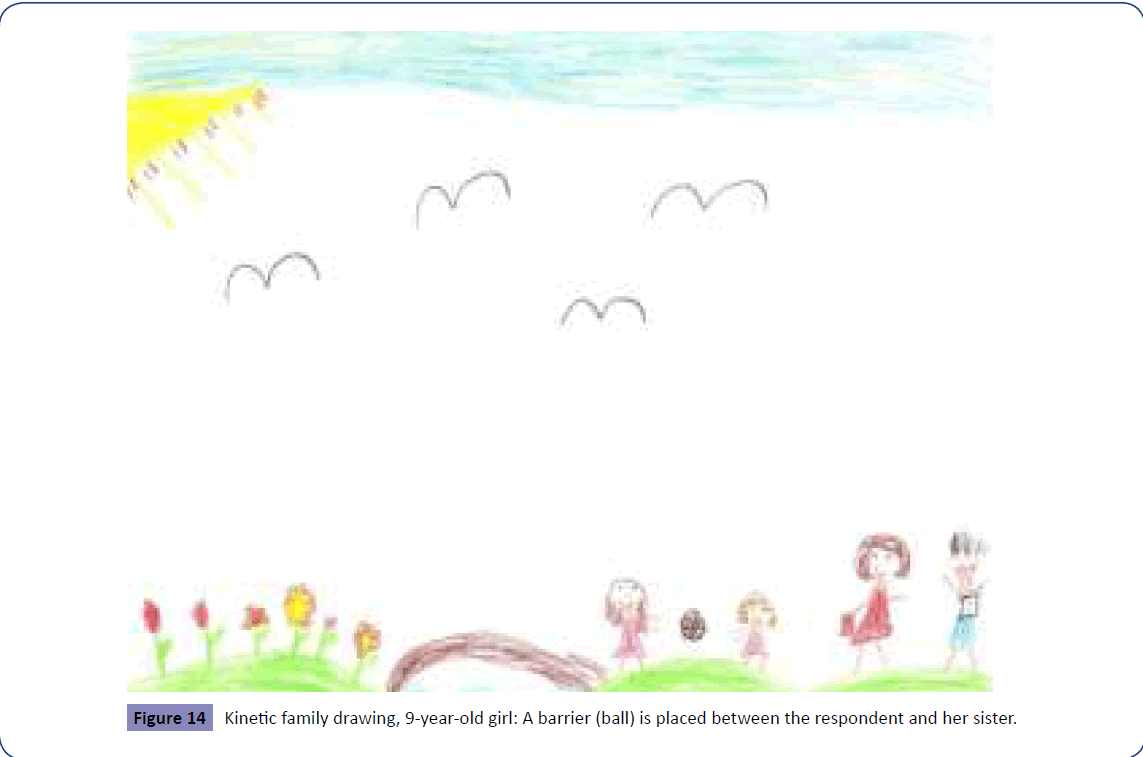

At first, we should consider the parental figures that the participants chose to draw, when the researcher asked for their families’ members. We could expect that the majority of the children would focus on the new household, created after the parental divorce. However the majority (69.2%) drew both parents in the kinetic family drawings (Figures 14-24). This choice may be connected with the fact that the parental divorce is a quite recent incident for the family context and the children may be confused.

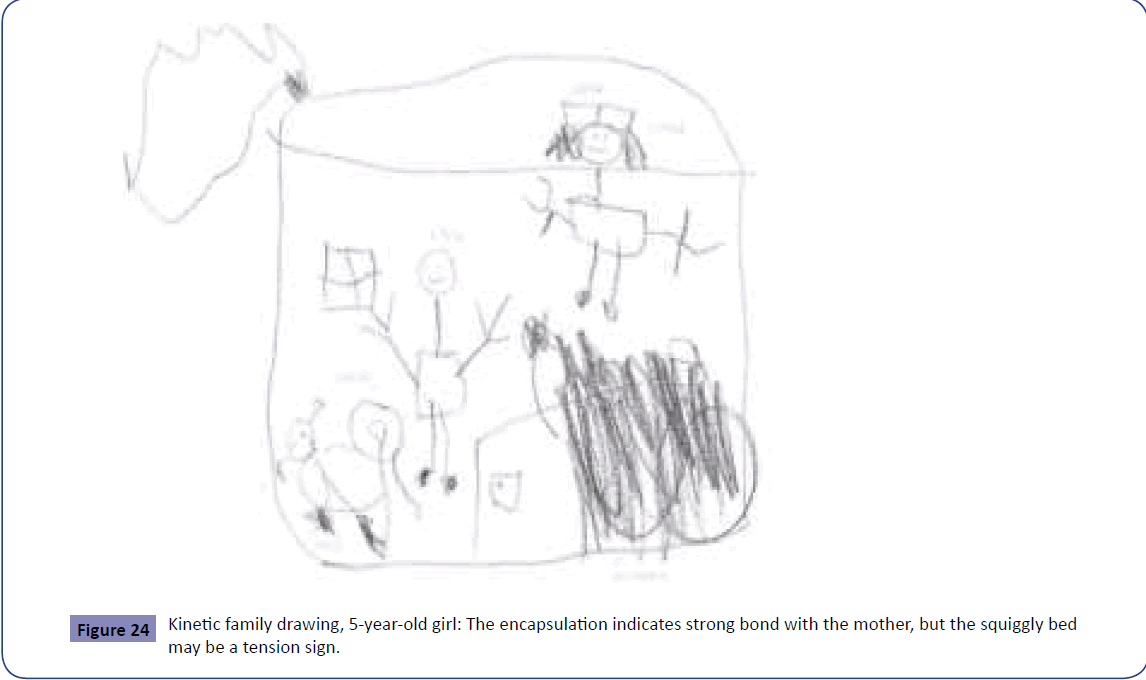

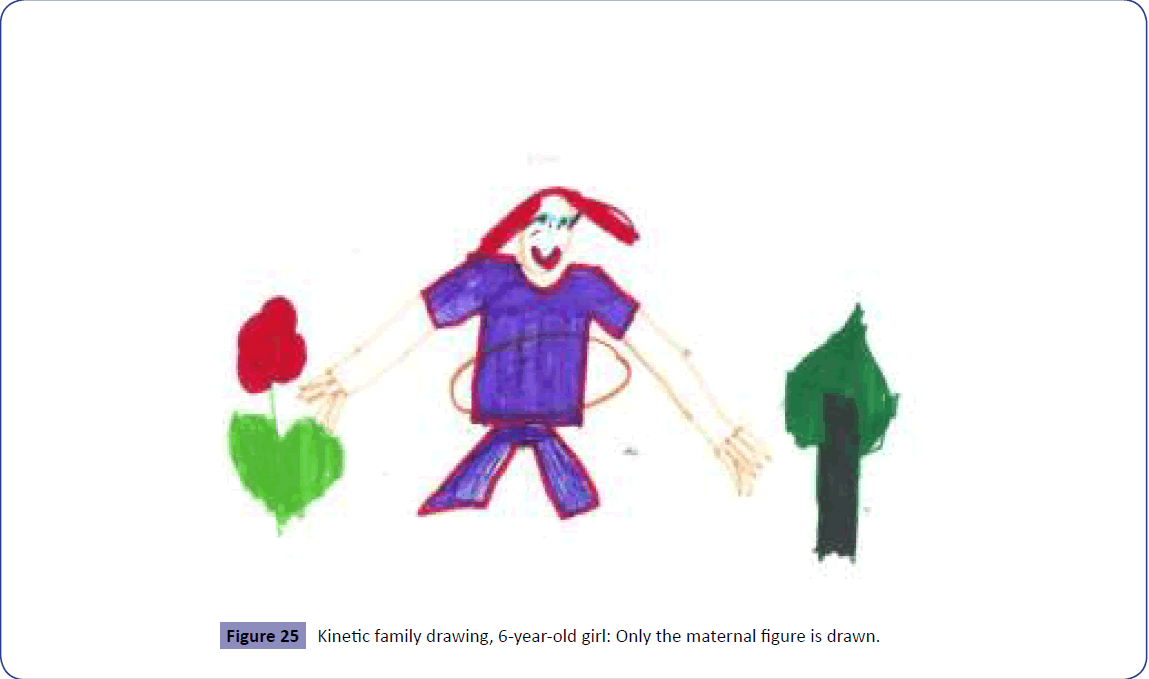

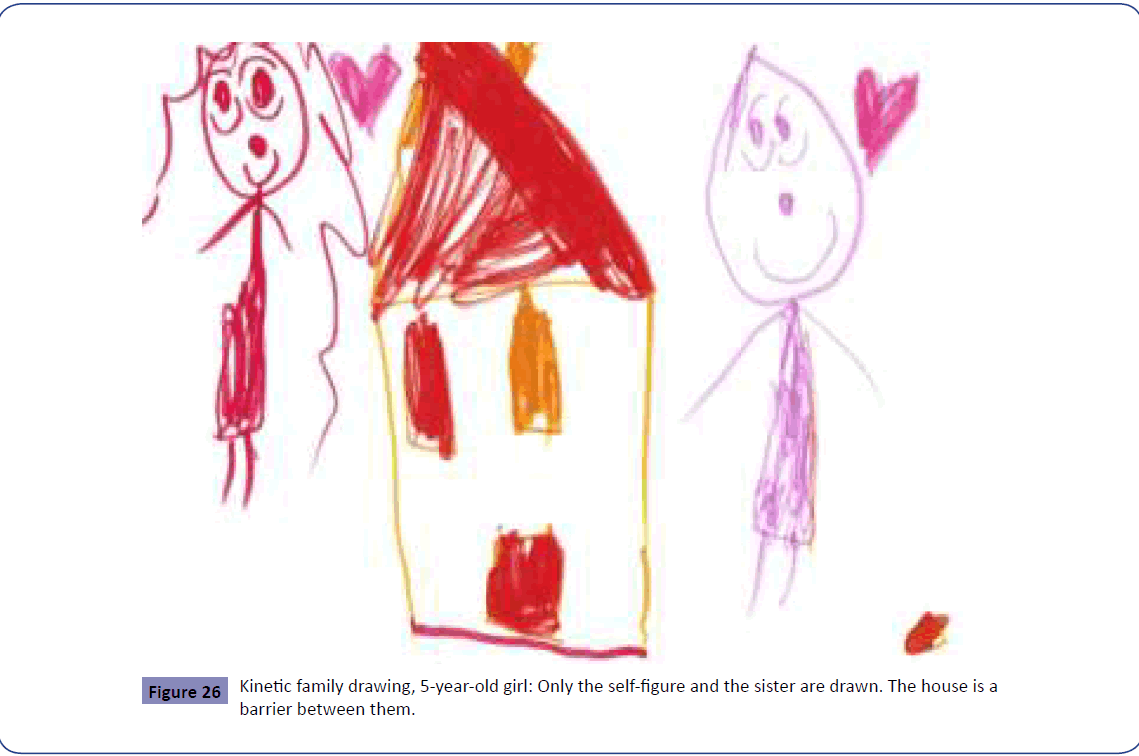

There is a significant percentage (23.1%), though, who drew only the maternal figure (Figures 23-25). Nevertheless, during the following conversation, these children referred to their fathers too, when the researcher asked if the drawn family has any other members, who are not included in the drawing [(Figure 23), 6-year-old girl: “Yes, dad has gone walking”]. Also a minority (7.7%) did not include any of the parental figures (Figure 26, 5-year-old girl: “Our parents are inside the house”).

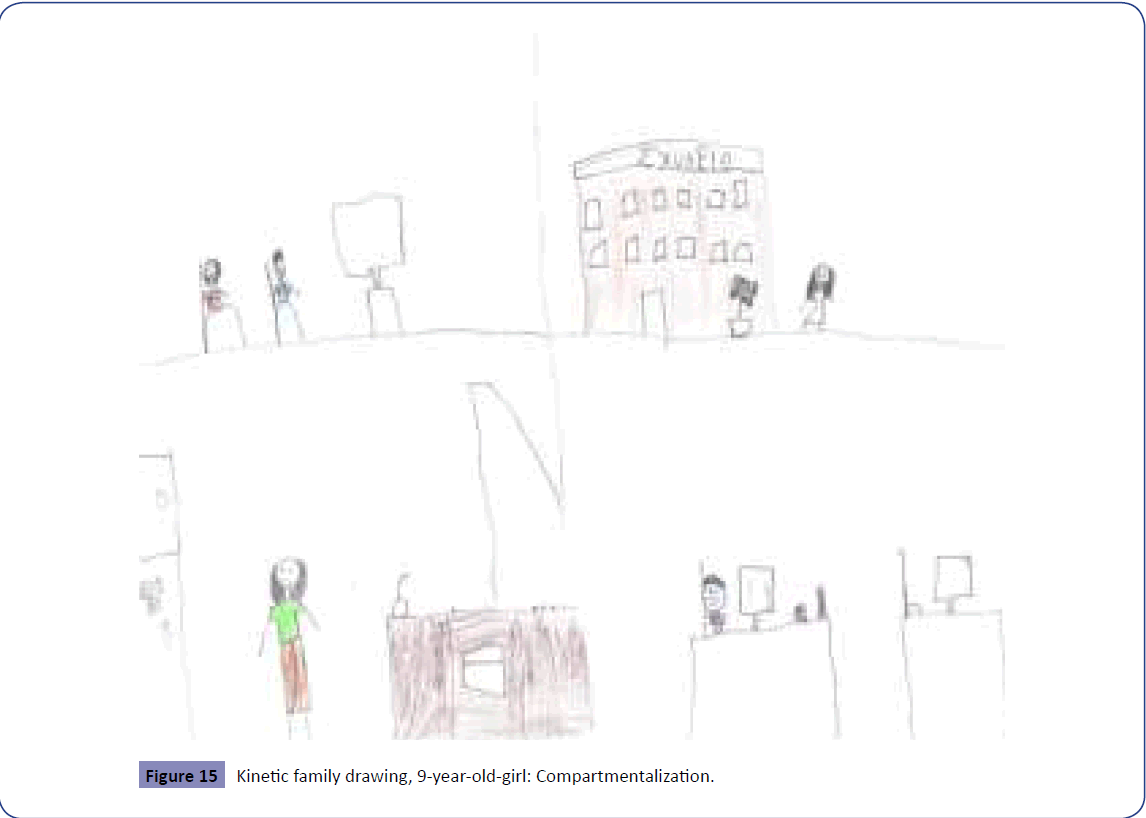

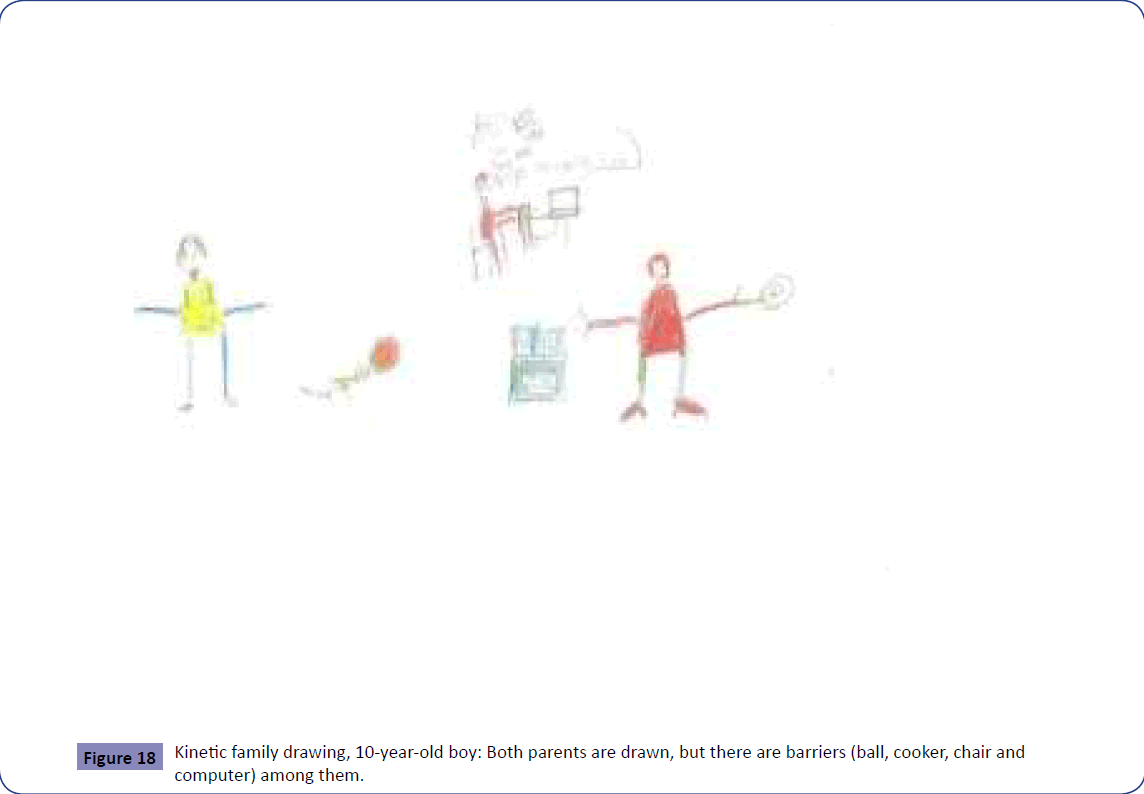

Except from the included figures, the size is also important in order to understand the children perceptions of themselves and the others. In the present study, almost the half of the participants (46.1%) included a large maternal figure in their kinetic drawings (Figures 15, 18, and 21-24). Nevertheless, even if the maternal figure seems large, she may be isolated, like in the Figure 8 (“compartmentalization”), indicating tension or distress [50].

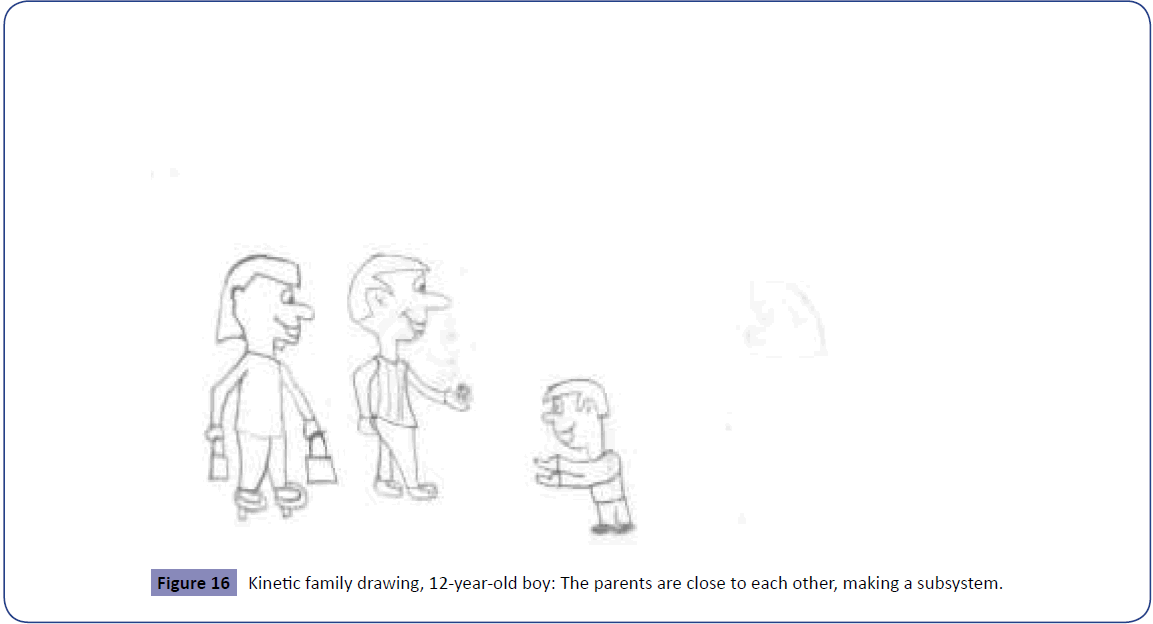

A significant percentage (23.1%), among the participants who included both parents, drew them same-sized (Figures 14, 16 and 18). These children are older than the average (aged between 9 and 11 years old). As a result, we could assume that they draw the parents that way, because they were reluctant or had second thoughts. It is very interesting the case of a 5-year-old girl (Figure 19), who included in her drawing her grandmother, making her the largest figure. This girl’s choice can indicate the bond between her and her grandmother, as well as the support that she might get from her.

In addition, the subsystems shown in the kinetic drawings are really noteworthy, giving information about the family system’s dynamics and its members’ roles. Specifically, we can consider either the interaction among the family members, or the place of the drawn figures. Consequently, we may observe two kinds of subsystems.

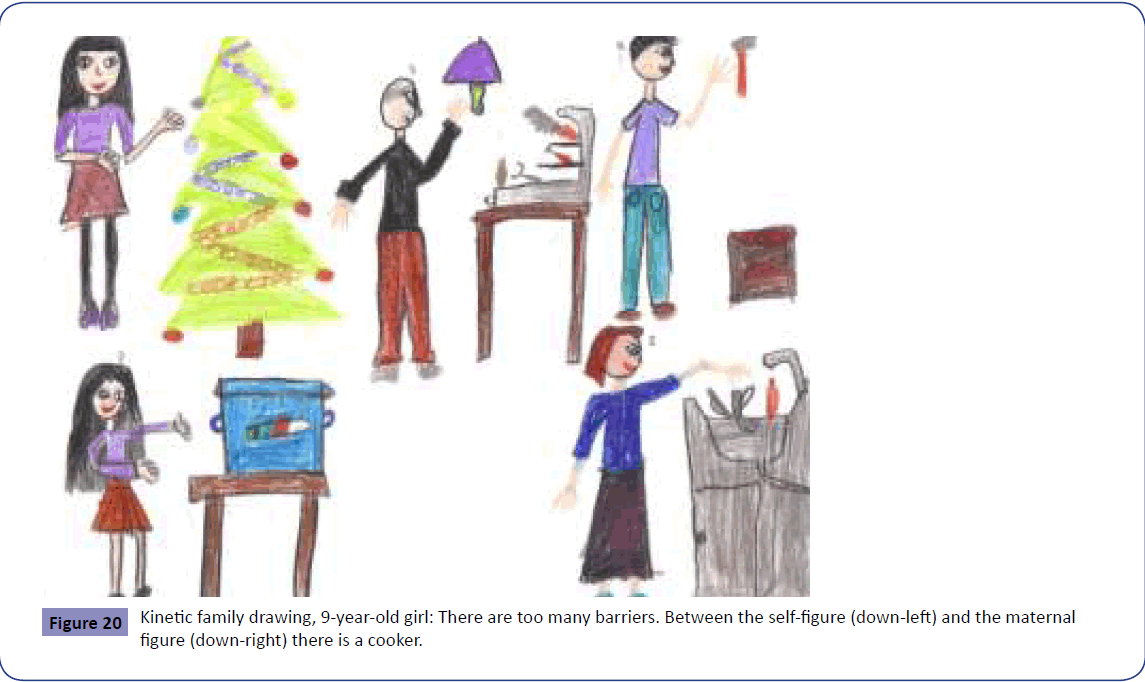

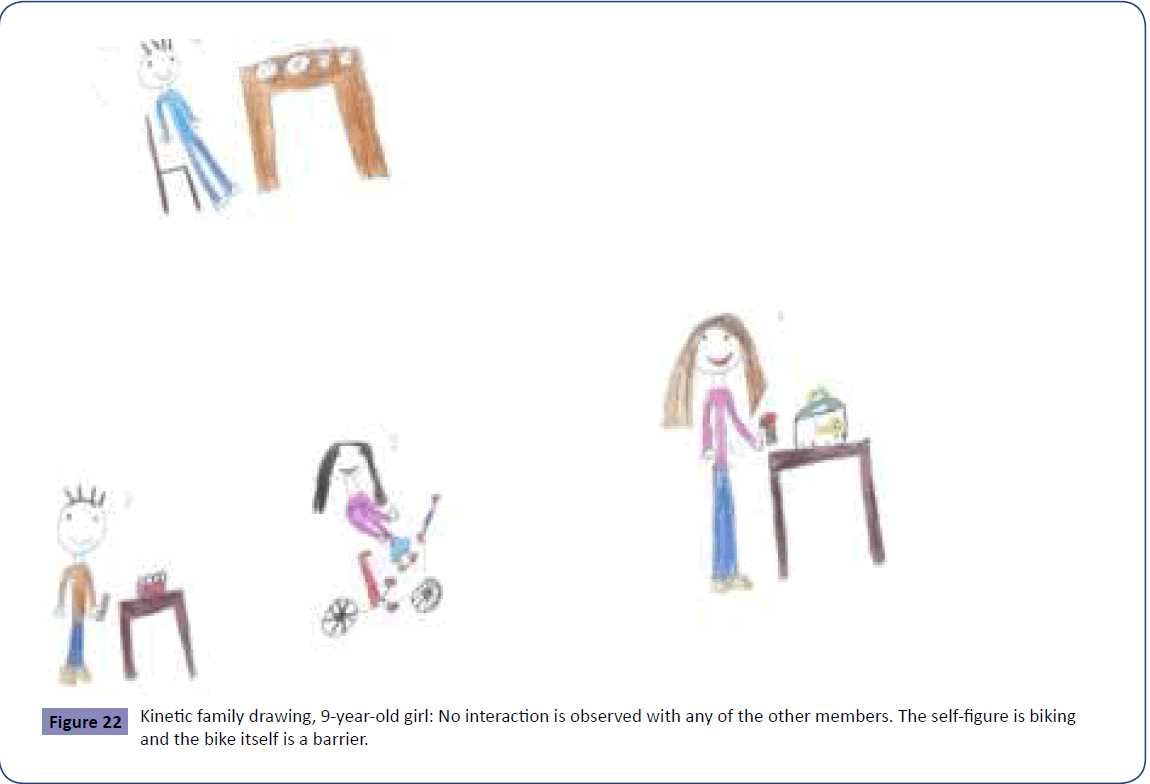

As for the subsystems resulting from the interaction among the drawn figures, we have to clarify that we took into account both, the drawings and the conversation in order to come up to the results. No interaction is observed between the respondent and any other member in almost half (46.1%) of the sample’s drawings (Figures 15, 18, 21, 22, 24, and 25). Children are either practicing an activity all alone (30.8%, e.g. Figure 24, 5-year-old girl: “I’m sleeping next to my mom”), or they do not include a self-figure in their drawings (15.4%, e.g. Figure 15, 9-year-old girl: “I’m inside school, waiting for my friend”).

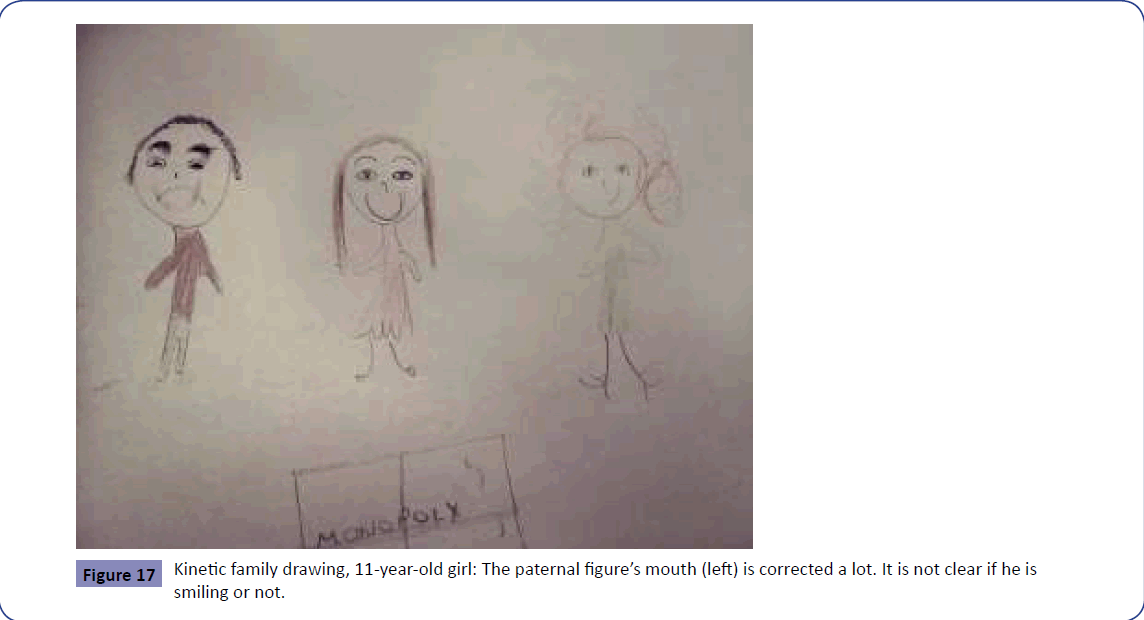

On the other hand, in the other half of the sample’s kinetic drawings (53.8%), respondents seem to interact with others, creating subsystems (Figures 14, 16, 17, 19, 20, 23 and 26). In the 15.4% of the drawings, the children participate in the same subsystem as both their parents (e.g. Figure 17, 11-year-old girl: “We’re playing the Monopoly with mom and dad”). Also in a 7.7% they interact only with the mother (Figure 20, 9-year-old girl: “I’m helping mom, while she’s cooking”) and in another 7.7% they interact only with the father (Figure 16). However, in the 23.1% of the sample, they choose to act together with the siblings or the friends, creating subsystems with them (e.g. Figure 26, 5-yearold- girl: “I’m playing in the garden with my sister”).

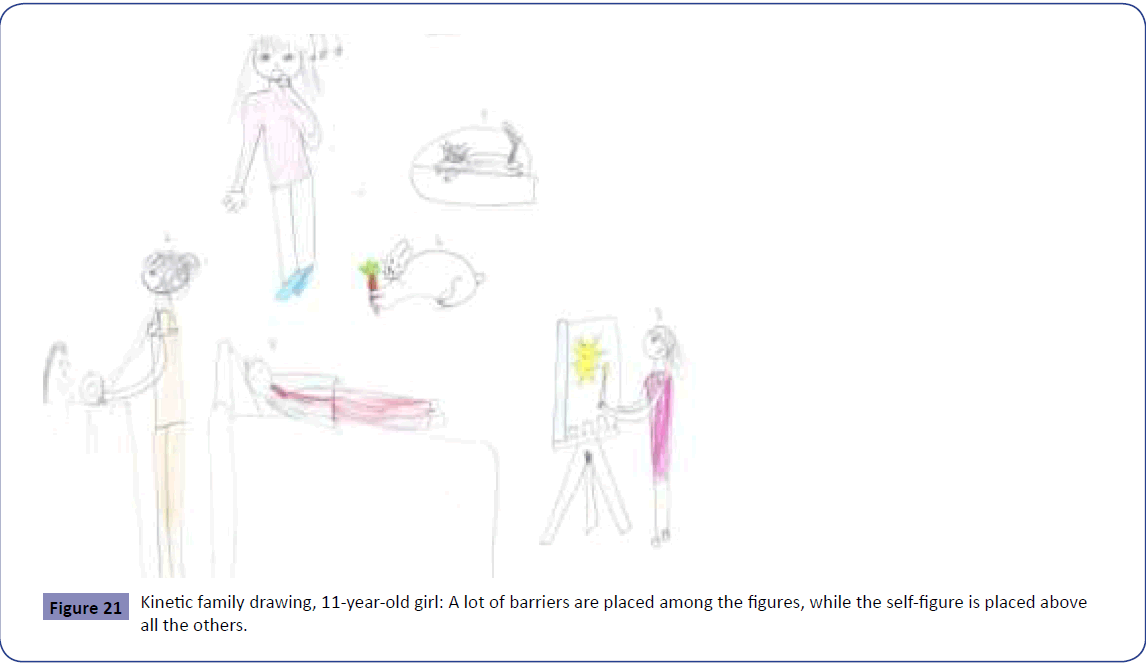

Looking more carefully at the sample’s kinetic drawings, we can observe that the interaction is not the only way to create a subsystem. As a result, we took into account the place of the self-figure and the ‘barriers’ placed between the drawn figures, in order to understand better the children’s point of view. In the vast majority of the kinetic drawings (61.5%) the self-figure seems to be isolated or not participating in any subsystem. Specifically, there are objects drawn among the figures (Figures 14 and 18: Ball, Figures 19 and 26: House, Figure 20: Cooker, Figure 22: Bike) or the self-figure is drawn away from the others. For example, in the figure 6 (12-year-old boy), it is obvious that the parental figures are drawn side by side, but the respondent placed the self-figure in the right side of the paper. Also, in the Figure 21 (11-year-old girl), all the figures seem to be on the ground and the self-figure is placed on the upper side of the paper.

On the other hand, in the minority of the sample’s kinetic drawings (23.1%), we can observe subsystems created among the children and other drawn members (Figure 17: Both parents, Figure 23: Siblings and cousins, Figure 24: Mother). For example, in the Figure 16 (5-year-old-girl) the respondent has placed the maternal and the self-figure together in a square frame (“encapsulation”), indicating maybe a strong bond between these two persons [50]. However there is no kinetic drawing, where the paternal and the self-figure create a subsystem. In the rest 15.4%, the self-figure is not included.

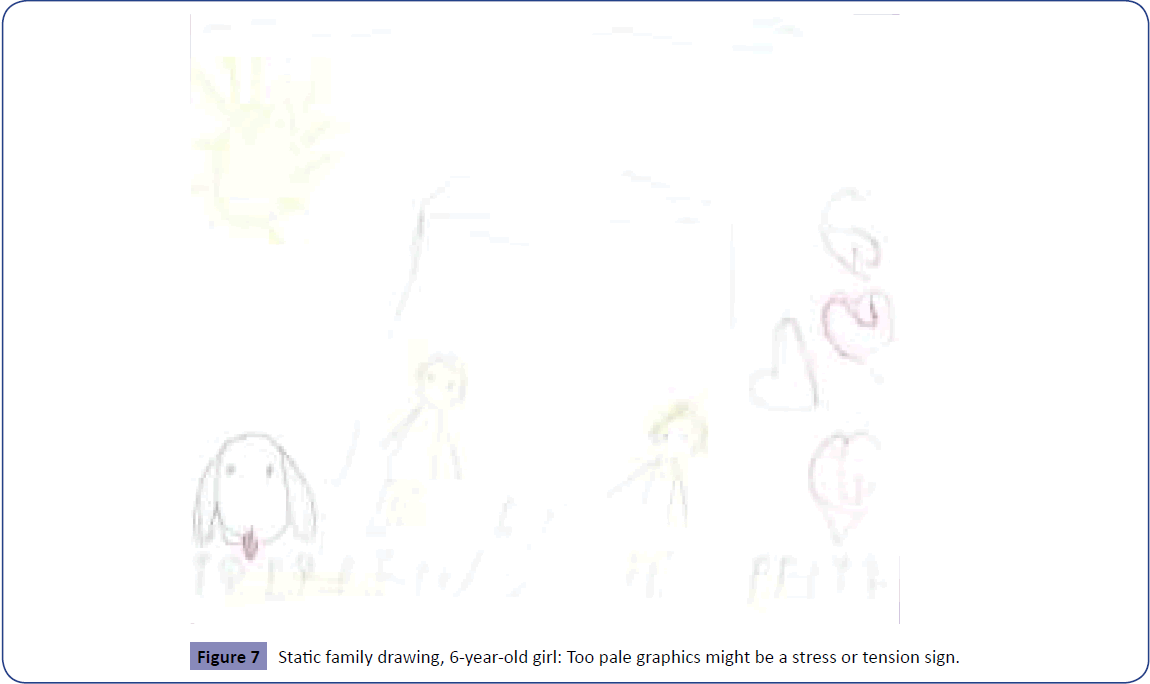

Except from the drawn figures and their actions or places, a way to obtain a general opinion about the drawing is to observe the respondent’s graphics. It is very interesting to see for example barely distinguishable figures in the 23.1% of the kinetic drawings (Figures 17, 19, and 24). The pale graphics may be connected with the respondent’s distress, especially when the figures are drawn without face-characteristics (Figure 23). Additionally, too many corrections during the drawing process (23.1% of the kinetic drawings) could represent the respondent’s second thoughts or hesitations. For example, in the Figures 16 and 22, the erased lines are still distinguishable and in the Figure 17, the father (on the left) is not clearly smiling. Last, the squiggly bed (Figure 24) might be another sign of tension.

Discussion

The present paper aimed to study the perceptions of schoolaged children about their families within divorce or separation crisis, in order to contribute to the research data concerning the first months after the parents’ separation or divorce incident. The presented data, focused on the parental divorce, is a part of a wider project concerning families in crisis which is still in progress. Another part though has already been published [57], enlightening the crisis due to recent parental unemployment.

One of our expectations, in the first place, was that we would be able to observe signs of tension and stress in the respondents’ drawings. According to the existing literature [1,2,4], stress is a common emotional situation of parents and children in parental divorce cases or other family crisis incidents [57,67]. The present study’s results confirmed the existing data, as in the majority (61.5%) of the kinetic family drawings, tension signs were observed (e.g. Figures 17, 19, and 23: Too pale graphics, Figures 16, 17, and 22: A lot of corrections, Figures 15 and 24: Compartmentalization or encapsulation).

While stress signs are obvious in a quite large percentage (61.5%), it is very interesting to see that the majority of the kinetic family drawings (69.2%) include both parents. Given that all of the sample’s respondents are living with their mothers, the fact that they include the fathers in the drawn household could indicate a close relationship between either the absent parent (father) and the child or the divorced mother and father [23-25,29]. However it is also possible that it is related to the children’s lack of adjustment [14-16,68] in the recent changing living conditions. For example, in Figure 17 (11-year-old girl, kinetic drawing) the respondent drew the self-figure between both the parental figures without any barriers or isolation drawing styles. Nevertheless, she seems quite confused, as she could not decide the right facial expression for her father. The father’s mouth is still obvious as happy and sad in the same time, after a lot of corrections and erasing.

Additionally it is very interesting to observe the size of the drawn parental figures, as well as the interaction with them and the respondents’ self-figures, in order to form an opinion concerning the bonds in the drawn families. As for the size, the maternal is the largest figure in the majority of the static drawings showing the respondents’ real family (60%) and in a large percentage of the kinetic drawings (46.1%). In any static or kinetic family drawing appears the paternal as the largest figure to be. It may be an indicator for the importance of a stable maternal figure for the sample’s children [21,22], given that all of them are living with their mothers, after the divorce.

Even if the drawn figures’ size shows the significance of the maternal figure, if we look closer, we might observe a different point of view concerning the interaction and the place of the drawn figures. Specifically, only in the minority of the kinetic drawings the respondents interact with either both parents (15.4%) or one of them (mother: 7.7%, father: 7.7%). However, this interaction mostly results through the conversation and it is not obvious through the drawings. The results concerning the interactions with the drawn parental figures tend to reject one of our expectations. We assumed that the sample’s children would interact and have a strong bond with the parent they are living with (mother), due to the support provided by her [18-22], but this is not obvious in the present study’s sample.

It is also intensified by the place of the respondents’ self-figures, as they utilize in a quite large percentage (61.5%) barriers or other drawing styles, isolating the self-figure. The resulting subsystems show lonely respondents, who may feel confused or have second thoughts about their emotions towards their family members. Even if the majority of the sample is female (84.6%) and all the respondents live with the mother, the results concerning the isolation if the self-figure tend to disagree with other researchers [26-28], who support the resilient relationship between the mother and the daughter in parental divorce incidents.

Last but not least, focusing on the support provided to the single parent’s family by the wider family members, we assumed that family members beyond the parents and the siblings would be included in the sample’s drawings. Indeed in the Figure 19 (5-year-old girl: Kinetic drawing), the respondent included her grandmother, who appears to be the largest figure. Also in the Figure 8 (6-year-old girl: Static drawing), the respondent included her aunt, stating that she chose her family because she likes her aunt’s home. Even if these examples are not the majority of the sample, the significant role of the wider Greek family indicated in the present study seems to confirm other researches [39-42].

Conclusion

To sum up, it is obvious that the majority of the sample’s children drew both parents in the static and the kinetic drawings. However, looking closer, they do not interact with the parents and they seem to feel mostly isolated. It could be related to the fact that the parents are very recently divorced or separated. Concluding, this research pointed some significant results about parental divorce or separation within the first months after the incident. Specifically, the present data focuses on the children’s perceptions of their families within crisis, contributing to the gap resulting from the existing literature review concerning the crisis time period. Nevertheless this paper consists a part of a wider project which is still in progress, enlightening a specific part of the sample. Hence the limited participants’ number and the selection of only one region of Greece consist limitations, letting us in no case to generalize this research’s conclusions. It would be very interesting to collect some follow-up data from the same sample or extend the study with a larger number of participants from other areas in Greece.

References

- Felner RD, Farber SS, Primavera J (1980) Children of divorce, stressful life events and transitions: A framework for preventive efforts. Prevention in mental health: Research, policy and practice 1: 81-108.

- Guttentag M, Salasin S, Belle D (eds.) (1980)The mental health of women. Academic Pressp: 23.

- Kalter N (1987) Long-term effects of divorce on children: A developmental vulnerability model. Am J Orthops 57:587.

- MonaghanJH, Robinson JO, Dodge JA (1979)The children's life events inventory. J Psychosom Res 23: 63-68.

- Felner RD, Ginter MA, Boike MF, Cowen EL (1981) Parental death or divorce and the school adjustment of young children. Am J Community Psychol 9: 181-191.

- Gadalla TM (2008) Impact of marital dissolution on men's and women's incomes: A longitudinal study. J Divorce Remarriage 50: 55-65.

- Aseltine R, Doucet J, Schilling E (2010) Explaining the association between family structure and early intercourse in middle class adolescents.AdolescFam Health 4: 155-170.

- Fomby P, Cherlin AJ (2007) Family instability and child well-being. Am Sociol Rev 72: 181-204.

- Guidubaldi J, Cleminshaw HK, Perry JD, Mcloughlin CS (1983)The impact of parental divorce on children: Report of the nationwide NASP study. School Psych Rev.

- Guttmann J, RosenbergM (2003) Emotional intimacy and children's adjustment: A comparison between single-parent divorced and intact families. EducPsychol 23: 457-472.

- Hetherington EM (1993)An overview of the Virginia Longitudinal Study of Divorce and Remarriage with a focus on early adolescence. J FamPsychol 7: 39.

- Amato PR (2001) Children of divorce in the 1990s: an update of the Amato and Keith (1991) meta-analysis. J FamPsychol 15: 355.

- Evans MDR, Kelley J, Wanner RA (2001). Educational attainment of the children of divorce: Australia, 1940–1990. Am J Sociol 37: 275-297.

- Ahrons CR (2004)We're still family: What grown children have to say about their parents' divorce. Harper Collins.

- Kelly JB, Lamb ME (2000) Using child development research to make appropriate custody and access decisions for young children. Fam Court Rev 38: 297-311.

- Moon M (2011)The effects of divorce on children: Married and divorced parents' perspectives. J Divorce Remarriage 52: 344-349.

- Nielsen L (1993) Students from divorced and blended families. EducPsychol Rev 5: 177-199.

- Baumrind D (1991)The influence of parenting style on adolescent competence and substance use. J Early Adolesc 11: 56-95.

- Lamborn SD, Mounts NS, Steinberg L, Dornbusch SM (1991) Patterns of competence and adjustment among adolescents from authoritative, authoritarian, indulgent, and neglectful families. Child Dev 62: 1049-1065.

- Milevsky A, Schlechter M, Netter S, Keehn D (2007) Maternal and paternal parenting styles in adolescents: Associations with self-esteem, depression and life-satisfaction. J Child Fam Stud 16: 39-47.

- Benson MJ, Buehler C, Gerard JM (2008)Interparental hostility and early adolescent problem behavior: Spillover via maternal acceptance, harshness, inconsistency, and intrusiveness. J Early Adolesc.

- Wood JJ,Repetti RL, Roesch SC (2004) Divorce and children’s adjustment problems at home and school: The role of depressive/withdrawn parenting. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev 35: 121-142.

- Booth A, Scott ME, King V (2009) Father residence and adolescent problem behavior: Are youth always better off in two-parent families?J Fam Issues.

- Flouri E (2006) Parental interest in children's education, children's selfÃÆâÃâââ¬ÃâÃÂesteem and locus of control, and later educational attainment: TwentyÃÆâÃâââ¬ÃâÃÂsix year followÃÆâÃâââ¬ÃâÃÂup of the 1970 British Birth Cohort. Brit J EducPsy 76: 41-55.

- King V, Sobolewski JM (2006)Nonresident fathers’ contributions to adolescent wellÃÆâÃâââ¬ÃâÃÂbeing. J Marriage Fam 68: 537-557.

- Argyrakouli E (2010) Quality of relationships between preschool children and their divorced mothers. Interscientific Health Care 2.

- Booth A, Amato PR (1994) Parental gender role nontraditionalism and offspring outcomes. J Marriage Fampp: 865-877.

- Herlofson K (2013)How gender and generation matter: Examples from research on divorced parents and adult children. FamRelatshSoc 2: 43-60.

- Kalmijn M (2013) Adult Children's Relationships With Married Parents, Divorced Parents, and Stepparents: Biology, Marriage, or Residence?FamRelatshSoc 75: 1181-1193.

- Gottman J, de Claire J (1997) The Heart of Parenting How to Raise an Emotionally Intelligent Children, Bloomsbury Pub Ltd.

- Gottman J, Silver N (2011)The Seven Principles for Making Marriage Work, Tantor Media.

- BabalisTH (2011) Children of single-parent families: Helping in school adaptation. Athens: Diadrassi (in Greek).

- Babalis T, Tsoli K, Nikolopoulos V, Maniatis P (2014)The Effect of Divorce on School Performance and Behavior in Preschool Children in Greece: An Empirical Study of Teachers' Views. Psychology 5: 20.

- Kogkidou D (2006) Children, parenting and society: What can we learn from single parents? In:Malikiosi-Loizou Μ,SidiropoulouDimakou D, Kleftara G (eds.)Counseling Psychology in Women. Athens: EllinikaGrammata (in Greek)pp: 136-167.

- Manolitsis G, Tafa Ε (2005) Checklist for detecting behavior problems in preschool age. Psychology 12: 153-178 (in Greek).

- Pliogkou V (2011)Which factors affect the education of children of single-parent families? From the perspective of lone parents.In proceedings of the 1stPanhellenic Conference of single-parent families on Single-parent families in modern society.Alexandroupoli: Association of single parents in the prefecture of Evros “Support” (in Greek), pp: 72-92.

- Babalis T, Xanthakou, Y, Papa C, Tsolou O (2011) Preschool age children, divorce and adjustment: a case study in Greek kindergarten.Electronic Int J Res Educ 9: 1403-1426.

- BabalisTH (2013) Dimensions of social exclusion and poverty among single-parent families in Greece. In: Daskalakis D (eds.)The Social Sciences and the Current Crisis. Athens: Papazisi (in Greek)pp: 459-489.

- Georgas D (2002)How much has family changed nowadays?Presentation in the 1stPanhellenic Conference for the Greek Family, Athens (in Greek).

- Giotsa Α (1999)The personal space and the neighborhood. A cross-cultural study in neighborhoods in Geneva, Athens and Kefallonia. Psychology 6: 124-136.

- Giotsa Α (2003) Values and emotional closeness among the Greek family’s members: Empirical data. In: Riga V (ed.) The Pandora’s box. Athens: EllinikaGrammata (in Greek).

- Mylonas K, Gari A, Giotsa A, Pavlopoulos V, Panagiotopoulou P (2006)Families across cultures: A 30-nation psychological study. In: Georgas J, Berry J, van de Vijver FJR,Kagitçibasi Ç, PoortingaYH (eds.). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, pp: 344- 352.

- Appel K (1931) Drawings by Children as Aids in Personality Studies. Am J Orthops 1: 129-144.

- Wolff W (1942) Projective methods for personality analysis of expressive behavior in preschool children. Character & Personality 10: 309-330.

- Hulse WC (1952) Childhood conflict expressed through family drawings. J Proj Tech Pers 16: 66-79.

- Porot M (1952)The drawing of the family: Browse by drawing the emotional situation of the child in his family.Pediatrie 7: 1.

- Brem-Gräser L (1957)Family as animals. Munich, Germany: Ernst Reinhardt.

- Corman L (1972)The test P. N. (vol. 1, 2, 3) Paris: Press Universitaires de France.

- Corman L (1990)The test family drawing. Paris: Press Universitaires de France.

- Burns RC (1982) Self Growth in Families: Kinetic Family Drawings (K-F-D) Research and Application. New York: Brunner/Mazel.

- Burns RC, Kaufman SH (1970) Kinetic family drawings (K-F-D): An introduction to understanding children through kinetic drawings. New York: Brunner/Mazel.

- Burns RC, Kaufman SH (1972) Actions, Styles and Symbols in Kinetic Family Drawings (K-F-D).An Interpretative Manual. New York: Brunner/Mazel.

- Biermann G, Kos M, Haub G (1975)The graphic test “the enchanted family” and its application in educational counseling and pediatric clinics. PadiatrPadol 10: 19-31.

- Gehring TM, Wyler IL (1986) Family-system-test (FAST): A three dimensional approach to investigate family relationships. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev 16: 235-248.

- Lilienfeld SO, Wood JM, Garb HN (2000)The scientific status of projective techniques. PsycholSci Public Interest 1: 27-66.

- Karella Μ (1991) Children draw the family. The revelation of the child’s psychodynamic situation. Athens: Kastoumi (in Greek).

- Giotsa A, Mitrogiorgou E (2014) Representations of Families through the Children’s Drawings in Times of Crisis in Greece. Int J Educ Cult 3: 2.

- Xanthakou Y (2007) Drawing an Imaginary Family. Athens: Atrapos.

- Handler L, Habenicht D (1994) The kinetic family drawing technique: A review of the literature. J Pers Asses 62: 440-464.

- Mylonakou-Keke I (1998)The children’s drawing “speech”: A throughout approach. Athens (in Greek).

- Mylonakou-Keke I (2009)When children speak through their drawings about themselves, their family and their world. Athens: Papazisis (in Greek).

- Tharinger DJ, Stark K (1990)A qualitative versus quantitative approach to evaluating the Draw-A-Family and Kinetic Family Drawing: A study of mood- and anxiety disorder children. Psychol Assess 2: 365-375.

- Elliott R (1995) Therapy process research and clinical practice: Practical strategies. In: Aveline M, Shapiro DA (eds.) Research foundations for psychotherapy practice. Chichester: Wileypp: 49-72.

- Elliott R, FischerCT, Rennie DL (1999) Evolving guidelines for publication of qualitative research studies in psychology and related fields. Br J ClinPsychol 38: 215-229.

- Cambier A, Pham HT (1985) Oedipal issues and representation of the family. Psychol Bull 369: 217-229.

- Fan JR (2012) A Study on the Kinetic Family Drawings by Children with Different Family Structures. Int J Art Des 10: 173-204.

- Giotsa A, Mitrogiorgou E (2014) Economic Crisis in Greece: Impact on Different Fields. In: Giotsa A (eds.) Psychological and Educational Approaches in Times of Crises – Exploring New Data. New York: Untested Ideas Research Center.

- Hetherington EM, Bridges M, Insabella GM (1998)What matters? What does not? Five perspectives on the association between marital transitions and children's adjustment. Am Psychol 53:167.

Open Access Journals

- Aquaculture & Veterinary Science

- Chemistry & Chemical Sciences

- Clinical Sciences

- Engineering

- General Science

- Genetics & Molecular Biology

- Health Care & Nursing

- Immunology & Microbiology

- Materials Science

- Mathematics & Physics

- Medical Sciences

- Neurology & Psychiatry

- Oncology & Cancer Science

- Pharmaceutical Sciences