The Dyslexia Dilemma: A History of Ignorance, Complacency and Resistance in Colleges of Education

David P Hurford, Jeremy D Hurford, Kimberly L Head, Michelle M Keiper, Samantha P Nitcher and Lauren P Renner

DOI10.4172/2472-1786.100034

1Pittsburg State University, Pittsburg, Kansas, USA

2Northeastern State University, Oklahoma, USA

- *Corresponding Author:

- David P Hurford

Pittsburg State University

Center for Reading, 1701 S. Broadway

Pittsburg, Kansas 66762, USA

Tel:620-235-4534

Fax: 620-235-6102

Email: dphurford@pittstate.edu

Received date: May 17, 2016; Accepted date: August 10, 2016; Published date: August 16, 2016

Citation: Hurford DP, Hurford JD, Head KL, et al. The Dyslexia Dilemma: A History of Ignorance, Complacency and Resistance in Colleges of Education. J Child Dev Disord. 2016, 2:3.doi: 10.4172/2472-1786.100034

Abstract

Dyslexia is the most common and widely studied learning disability affecting nearly 20% of the children in the United States. Although the Science of Reading provides considerable information with regard to the nature of dyslexia, its evaluation and remediation, there is a history of ignorance, complacency and resistance in colleges of education with regard to disseminating this critical information to pre-service teachers. Information concerning weaknesses in the training of doctoral-level faculty which trickles down to graduate students in education and pre-services teachers is discussed along with potential solutions. Children with dyslexia and reading difficulties are waiting to be taught to read and the knowledge and skills necessary to do so exist. It is essential that the Science of Reading become part of the vocabulary, knowledge base and training within colleges of education.

Keywords

Dyslexia; Education; Teacher Training; Reading Difficulties

Introduction

Reading acquisition is one of the most complicated and important skills in which humans engage. In our culture, the social and economic success that a person enjoys is very much related to his or her reading skills. There is hardly a career or job that does not depend on some level of reading proficiency. This was not always the case. An examination of the past 150 years indicates that the number of skilled labor jobs [1-3] and the number of family-owned farms has declined [4], and the need for a high school diploma has increased [5,6]. In the past, individuals who had difficulties learning to read could find gainful employment that did not require a high school education or the ability to read. This is simply not the case in contemporary society. As a result, all children need to learn how to read and they need to have adequate reading skills as adults, beyond simply reading for pleasure. Poor reading skills can act as a barrier for social engagement and influence [7]. As a result, the development and maintaining of adequate reading skills are of paramount importance.

Unfortunately, for the nearly 20% of individuals in the United States who have dyslexia, reading acquisition is painfully difficult [8,9]. Dyslexia is the most widely studied and common learning difference. In addition to the various academic problems associated with dyslexia and poor reading skills, individuals with dyslexia also suffer poor self-esteem [10], can become depressed, suicidal, and experience post-traumatic stress [11,12] are more likely to abuse substances, be victims of parental physical abuse [13], drop out of school [14], be adjudicated as juveniles [15] and later as adults [14] and are more likely to live in poverty [14]. Dyslexia and reading difficulties are not only a very serious academic issue, but are also very serious social issues. Fortunately, reading scientists have discovered the nature of the fundamental systems involved in reading failure. The term the Science of Reading refers to the corpus of knowledge that includes what science has determined to be relevant to reading, reading acquisition, assessment of poor reading and the interventions available for poor readers. The Science of Reading involves precisely what science has discovered to be relevant not only to reading, its subskills and reading acquisition, but how to modify experiences such that struggling readers and individuals with dyslexia can become competent readers. This knowledge includes phonology, phonics, orthography, fluency, vocabulary, comprehension, neuro-processing as it relates to reading and its genetic basis, visual, perceptual and memorial processing, the various writing systems, the alphabetic principle, letter-sound correspondences, among other areas.

Insuring that pre-service teachers are competent in applying their knowledge of the Science of Reading is critical in reducing reading failure and poor performance in reading [16]. The scientific evidence contained within the Science of Reading has guided the creation of interventions that are successful in assisting individuals with dyslexia and reading difficulties to become competent readers. Given the potentially disastrous negative effects of dyslexia and the likely loss of contribution that an individual with dyslexia can make toward society due to the barriers inherent in the current educational system; utilizing strategies to assist individuals with dyslexia to become competent readers, and thus, able to make a contribution to themselves, their families, communities and society is critically important.

Dyslexia is characterized by difficulties with accurate and/or fluent word recognition and by poor spelling and decoding abilities. These difficulties typically result from a deficit in the phonological component of language that is often unexpected in relation to other cognitive abilities and the provision of effective classroom instruction. Secondary consequences may include problems in reading comprehension and reduced reading experience that can impede growth of vocabulary and background knowledge” (International Dyslexia Association). Specifically, although the exact mechanisms are not completely elucidated, dyslexia involves a great difficulty in manipulating the sounds of language, difficulties in assigning the sounds associated with their representative letters and decoding letters into the sounds that they represent. These difficulties pose barriers to fluent reading which then causes comprehension to be lacking or absent, spelling and writing difficulties, and a host of other related problems.

Speech Acquisition and Learning to Read

The ability to learn to speak is natural and relatively effortless for nearly all infants and toddlers. For most infants, simply exposing them to a language guarantees that they will learn the language. Regardless of nationality, infants are natural language learners and are generally born with the ability to utter all of the sounds that humans are capable of producing [17-21]. After some time in a particular language environment, the infant will stop producing some sounds in favor of those that he or she is consistently hearing. The infants and young toddler's vocabulary also increases in leaps and bounds. For the most part, this process is seemingly so automatic and effortless that Noam Chomsky theorized that infants are born with a Language Acquisition Device [22,23]. The LAD is a theoretic neurological device whose primary purpose is to help the individual to acquire language with relative ease. The only requirement is that children must be exposed to language on a frequent and consistent basis. Their neurological systems recognize the patterns and conventions of the language and the child appears to “learn” the language rather effortlessly. Although individuals may be born with LADs that help them to acquire spoken language skills, it seems to have a limited life. The LAD seems to be present at birth and remains intact until the individual acquires his or her spoken language. After early childhood, the ability to easily and effortlessly acquire languages is diminished. This reality is experienced by anyone who attempts to learn a second language after middle childhood. At this point, learning an additional language becomes quite effortful.

Learning to read, on the other hand, is not a natural process and is a task in which children must exert tremendous cognitive effort [24,25]. Providing young children exposure to text does not result in spontaneous reading. Children must map the sounds for which they are already familiar to the letters used to represent them. They must learn how to use the knowledge of these relationships to decode words, synthesize individual sounds into words, and then recognize the word as a word that they have in their vocabulary. Lastly, and most importantly, the child must be able to comprehend the written material. Comprehension is the goal of the reading process, but is typically dependent on all of the preceding skills any of which could cause difficulties for comprehending text. As already noted above, many of our nation’s children have grave difficulty learning to read. Learning to read is certainly an effortful act that can be delayed if children do not have the prerequisite skills to become adequate readers [26,27].

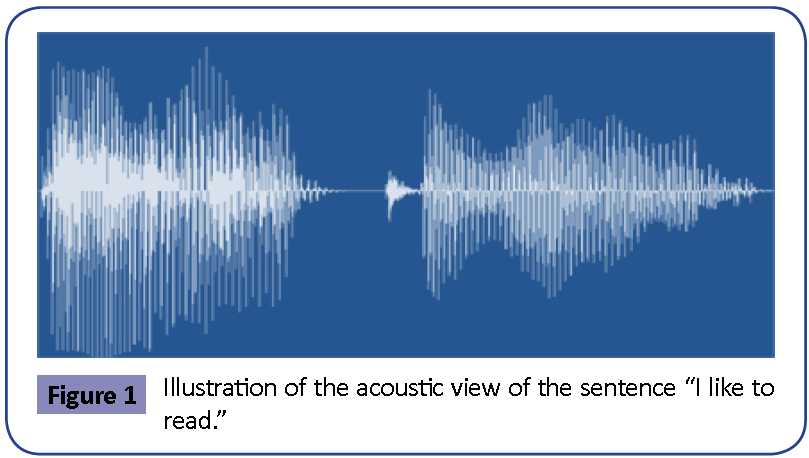

Speech evolved as a mechanism for humans to communicate and is a neurologically expected event [28]. An examination of an infant’s development includes the progress made in relation to learning to speak. Reading, on the other hand, is an invention of humans that took advantage of neurological systems that evolved for purposes other than reading [29]. The spoken word is transcribed into symbols that represent the various aspects of the language. An individual must learn the association between those symbols and their sounds and how to apply that knowledge to the process of reading. The reading process is not “pre-wired” into the brain as has been argued for speech development. As an example, at the time of birth, infant’s process speech sounds in a categorical manner without prior experience. Acoustically, speech is a continuous phenomenon. However, we hear each sound or phoneme in words categorically. That is, we can distinctly hear the specific sounds in a word. However, when viewing speech signals acoustically, it is difficult to determine where the beginning and end of a sound or word is. In Figure 1 the sentence “I like to read.” is presented. One of the reasons that it is difficult to determine the demarcation point for sounds and words is that the sounds overlap each other even though we hear the sounds categorically.

Human brains are able to make sense of acoustic information without actually learning to do so. They are uniquely prepared for their language environments and are ready to begin the process of speech acquisition. This is simply not the case for reading. To learn to read effectively, one has to exert considerable effort and energy and to come to understand that the written language is a code that represents the spoken language.

Writing Systems

There are many different ways to communicate meaning through symbols. Logographic systems do so by representing words, phrases or concepts to symbols. The Chinese logographic system represents syllables. As an example, two Chinese logographs are used to represent the word “reading;” Read. To be fully literate in Jiantizi, an individual would need to know approximately 3,000- 4,000 logographs. To learn this large number of logographs is extremely time-consuming and challenging. There have been unsuccessful attempts to replace the logographic system with an alphabetic system as the alphabetic system is much more economical when examining the mnemonic effort required to learn logographs compared to alphabets [30].

The English Writing System uses symbols as well, but rather than representing morphemes or meaning, letters are used to represent the sounds or phonemes of the English language. The great advantage of doing so concerns the enormous number of words that a reader of the English Writing System can read and, as a result, has access to from a very early time in the individual’s reading development. Additionally, when new words are encountered, the proficient reader generally has the skills to read the word successfully. Essentially, once the individual comprehends that sounds are represented by letters, the most probable combinations of particular letters, and the many variations in which specific sounds can be represented, the number of words that this individual could read is practically limitless. However, the writing system should represent the spoken language in terms of fit as well. Some languages are more easily represented by logographs, syllables or alphabets.

A transparent writing system is a writing system in which each sound of the language is represented by one and only one symbol. In addition, each symbol represents one and only one sound. There is a direct relationship between the sounds and their symbols. Examples of transparent writing systems include Greek, German, Finnish, Serbian, and Turkish.

Practice translating or decoding the symbols into their sounds helps the individual become more efficient. Once an individual has repeatedly practiced a skill it becomes increasingly more proficient and can become nearly automatic. Cognitive scientists define an automatic process as a process that requires little or no cognitive energy to perform [31,32]. Each individual has cognitive skills and abilities and a finite amount of cognitive energy. When a task is very difficult or effortful most or all of that cognitive energy is required to perform that task. Practice begets efficiency and efficiency requires less cognitive energy.

When individuals have been reading for many years, it is likely that the initial reading processes will become automatic. That is, the reader may require little cognitive energy to perform decoding and synthesizing skills. For the skilled reader, what is being read seemingly and instantaneous transfers from text to meaning. The beginning reader very carefully decodes each letter into its respective sound and then synthesizes those sounds into words until he or she has read every word in the sentence. This process is deliberate and time consuming and requires an enormous amount of cognitive energy. However, as individuals practice these skills, they become more efficient, and as a result, require less cognitive energy. As the analysis (decoding) and synthesis (blending) skills become more automatic, the savings in the use of cognitive energy can be applied to other cognitive tasks such as comprehension [33].

Neurologically, individuals with dyslexia learning to read a transparent writing system are just like children who experience reading failure with the opaque English writing system, but since the transparent writing system is less burdensome to decode, their experience with reading failure results in very slow reading rather than being bogged down in the quagmire as is the case for children learning to read an opaque writing system. Additionally, students who are learning to read in languages that have transparent writing systems begin formal reading acquisition training later and end it sooner than those children who are learning to read in writing systems that are not transparent.

An opaque writing system does not have a one-to-one system for representing sounds like the transparent writing system. English employs one of the most opaque writing systems, has been influenced by many languages and continues to evolve each day. It is a dynamic and fluid language that embraces change. The English writing system has allowed each of the languages that have influenced English, such as Anglo-Saxon, French, Latin, Greek, and Danish, to retain their writing systems. Some of those languages are also opaque. As a result, learning to read English is an extraordinarily difficult enterprise. J. R. Firth, in 1937, stated, “English spelling is so preposterously unsystematic that some sort of reform is undoubtedly necessary in the interest of the whole world.” Mastering the English writing system involves great time and effort on the part of the learner because of the borrowing and using of other writing systems with their unique spelling protocols. As an example, there are several alternative spellings for the “e” sound (e.g., “e,” “ee,” “ea,” “y,” “e-consonant-e,” “ie,” “ei,” “ey,” “i,” etc.) just as there are alternative spelling for several sounds. Some sounds are represented by digraphs (e.g., “ow,” “ou,” “sh,” “th-voiced,” “th-unvoiced,” etc.) and vowels are modified if they are followed by the letter “r” (r-controlled vowels, e.g., “ar,” “ir,” “er,” “ur,” etc.). To complicate the system further, there are different spellings of words based on context (e.g., “to,” “too,” and “two;” “threw” and “through;” “tow” and “toe,” etc.). Children begin the process of learning to read an opaque writing system earlier than their transparent-writingsystem peers and take much longer to learn it.

It is necessary for beginning readers to acquire the alphabet principle [34-36]. That is, to understand that sounds are represented by letters. Reading an alphabetic writing system involves translating the written code into its phonemes and synthesizing those phonemes into words. Unfortunately, individuals with dyslexia have grave difficulty decoding the written text into sounds and then synthesize them into words and the basis for this difficulty appears to be related to poor phonological processing skills [37,38]. Improvement in phonological processing requires explicit instruction and intervention in children with dyslexia [39,40]. Waiting to determine if the child will spontaneously acquire these skills is problematic [41]. A child with dyslexia must have explicit training to develop the skills necessary to learn to read. It has been known for some time that children who are not given explicit training to resolve their phonological processing deficiencies become adults who experience illiteracy [42].

The History of Ignorance, Complacency and Resistance

The science is relatively clear on issues related to reading acquisition, how to teach reading, the causes of dyslexia and reading failure and how to identify and provide remediation strategies for children with dyslexia and reading difficulties [43-45]. The history within colleges of education has been a resistance to the Science of Reading, widespread ignorance and complacency. In each case, colleges of education faculty have ignored the scientific knowledge that informs reading acquisition and the identification and intervention strategies for struggling readers. As a result, the pre-service teachers who are being educated at these institutions fail to receive the necessary training that would allow them to be effective in providing remediation to students with dyslexia [46]. “For the greatest enemy of truth is very often not the lie—deliberate, contrived and dishonest—but the myth—persistent, persuasive, and unrealistic. Too often we hold fast to the clichés of our forebears. We subject all facts to a prefabricated set of interpretations. We enjoy the comfort of opinion without the discomfort of thought” [47].

The results of this ignorance, resistance and complacency can be seen at many levels. The Nation’s Report Card indicated that 33% of fourth graders were reading at a level below Basic and 58% are reading at a level below Proficient. Reading at the Basic level indicates partial mastery of the skills necessary for proficient work at a particular grade level. Reading at the Proficient level denotes appropriate academic performance in which students have demonstrated their competency to read challenging material [48]. These percentages have not changed appreciably since 1992 when the percentage of students reading below Basic and Proficient were 38% and 55%, respectively [48]. Although considerable concern and effort have been placed on issues related to students who are performing poorly in reading, the data suggest that not much progress has been made in student performance even though the Science of Reading has established how reading acquisition occurs and how to remediate the deficient skills and subskills related to reading.

The concerns regarding reading are certainly not new. Three decades ago, the National Commission on Excellence in Education provided ample evidence that many of our nation’s children experienced academic difficulties that resulted in poor reading and mathematics proficiency. These difficulties were also found to persist into adulthood [49]. Since that time several key pieces of legislation were enacted that attempted to rectify these issues (Improving America’s Schools Act, 1994; Goals 2000: Educate America Act, 1994; No Child Left Behind Act, 2002). Although these efforts provided illumination of the difficulty, and in the case of the No Child Left Behind Act enormous accountability requirements for school systems, academic performance has not changed and a nearly equal percentage of students are continuing to experience reading failure. Educational critics have argued that poor classroom instruction, particularly for very lowperforming students, is responsible [50]. One could argue that accountability aspects of these pieces of legislation, particularly No Child Left Behind, resulted in poor performance on reading tests. The requirement that testing be used to determine the academic progress of students necessarily reduced the time that teachers could spend teaching basic skills in the classroom due to increased need to teach students how to pass high-stakes testing. This argument seems unlikely for several reasons, most notably that poor reading performance existed prior to the enactment of legislation and that the raison d’etre for the legislation was specifically to increase reading skills. As discussed above, a very large percentage of teachers lack the basic knowledge that is required to teach reading acquisition [51,52]. This unhappy fact would seem to play a very large role in the reason that students are performing so poorly on high-stakes reading tests. In fact, if teachers were successful at “teaching to the test,” performance would have increased on reading tests. The fact of the matter is that teachers do not receive training in the Science of Reading which leads to an inability to provide appropriate instruction in the classroom.

There is considerable scientific knowledge concerning reading acquisition and the strategies that are the most effective in teaching children to read [53-56]. Classroom instruction that teaches these skills related to the Science of Reading is more effective than those that do not. Unfortunately, it appears that these skills and the components of the Science of Reading are often not directly taught to many pre-service teachers [57-59].

Approximately 53% of pre-service and 60% of in-service elementary teachers who will be most responsible for assisting students with reading acquisition, were unable to correctly answer half of the questions regarding knowledge of language structure [60]. Only 20% of 722 teachers could segment words into speech sounds; only 30% correctly identified the number of phonemes in half the items; a n d only 60% positively identified the irregular words in a list of 26 words. D u r i n g debriefing, teachers reported that they had not received formal instruction regarding the complex structure of phonological processing during their academic training [52].

Despite being experienced and well-educated, teacher participants generally demonstrated low levels of the explicit, specialized knowledge necessary to effectively provide reading instruction to students [61]. Pre-service teachers were also found to overestimate their knowledge [52].

Teacher training programs generally fail to provide adequate instruction and acceptable resources regarding how to teach students to read. Instead, teachers must rely on their own skills and on other resources to learn how to teach reading. Most colleges of education encourage pre-service teachers to “develop their own personal philosophy of reading” [58] rather than teach pre-service teachers the mechanics of the Science of Reading. Such misguided encouragement results in a considerable variety of positions regarding teaching reading, most of which are inconsistent with the Science of Reading, and thus with reality.

Not only are teachers not receiving adequate preparation, they also are not provided with appropriate resources during their training. In a 2006 examination by the National Council on Teacher Quality (NCTQ) of college-level reading courses, the authors considered a textbook to be an acceptable example of a core resource for the course if it thoroughly presented the five components of reading instruction which were identified by the National Reading Panel as phonemic awareness, phonics, fluency, vocabulary and comprehension [59]. The four textbooks found to be acceptable in a survey of 227 were used in less than five percent of the courses examined. Often, inaccurate information was presented in widely used textbooks [62].

It has been documented that teachers are not providing beginning readers with consistent and adequate reading instruction. Reading failure rates have not changed appreciably in several decades even though the scientific literature regarding reading, its subskills and proper teaching techniques have been repeatedly substantiated. It is clear that pre-service teachers are not receiving proper instruction regarding the Science of Reading. Pre-service teachers, experienced teachers, and university instructors all perform poorly on measures of constructs relating to reading acquisition and literacy. Thus, the lack of the knowledge related to the Science of Reading could be the reason for the resistance in teaching these concepts to future generations of teachers. An alarmingly small number of teacher education programs provide coursework that presents the appropriate knowledge base of the Science of Reading to its students, hence the impetus of Greenberg, McKee and Walsh’s [58] work to link evaluative scores to colleges of education so that individuals who have a desire to become teachers can make informed decisions regarding matriculation.

In their eight-year study to develop and implement a method to examine teacher education programs, only 22% of the 594 teacher certification programs involved in the study received scores of three or higher on a four-point rating scale [58]. Additionally, 78% of the elementary education programs received scores of 0 (“program coursework does not adequately address strategies for struggling readers,” p: 41) for Standard 4 (Struggling Readers) which is the standard most germane to this discussion.

The lack of knowledge regarding the Science of Reading witnessed in pre-service teachers, in-service teachers and their professors is paramount to complacency, ignorance and resistance and falls fully on colleges of education who willfully and knowingly resist disseminating the Science of Reading to their students. Faculty in colleges of education often have insufficient training in science and research methods such that they are not able to read the research available that would inform them of the content of the Science of Reading. As an example, the weaker the training in research the more likely that an institution offers an Ed.D. rather than a Ph.D. in education [63]. Further, Townsend [64] expressed that many Ed.D. programs lack value and are “seen as a watered down version of the Ph.D. in Education and seemingly fail to provide practitioners with the knowledge, skills, and behaviors for effective leadership in educational settings” [64]. Faculty in colleges of education often do not possess the skills necessary to read, understand and critically evaluate the scientific literature concerning the cognitive, linguistic, neurological, etc. components of reading. Boote and Beile [65] discovered that literature reviews for dissertations en route to the Ed.D. were generally weak, lacked substance and failed to demonstrate that the candidate had a firm grasp of his or her field. Without training in research which includes first and foremost an understanding of the literature in one’s field, individuals cannot be consumers or contributors to this literature. When faculty lack training in research and science, they are susceptible to strategies that are not aligned with science and therefore not appropriate. As a result, parentled- grass-roots organizations are leading the charge to transform colleges of education and to require that they teach the Science of Reading so that identification and intervention techniques can be used to teach children with dyslexia.

An approach that has permeated the education of pre-service teachers and is antithetical to the Science of Reading refers to an approach referred to as whole language (WL). Goodman [66,67], who developed the WL approach, conceptualized learning to read in a similar fashion as language acquisition described by Chomsky. Goodman argued that learning to read is natural and should mirror the development of language acquisition [68]. It was argued that exposure to print should result in literacy in the same way that exposure to a language results in language acquisition. Unfortunately, reading development does not occur as a function of mere exposure to print as language does; nor is reading acquisition a function of a “psycholinguistic guessing game.” Smith [69,70] suggested that focusing on phonemes deterred children from learning to read and that “children learn to read only by reading” [70]. Learning to read requires explicit and systematic instruction, language acquisition does not. An alphabetically-based writing system, such as that which is used in English, represents the sounds of the language with letters. The English Writing System, like all alphabetic writing systems, is a code. Access to phonology occurs as a function of deciphering the symbols into their respective phonemes. Once an initial understanding of the relationship between sounds and their symbols has been developed, decoding and reading acquisition training commences. Its reciprocal process, encoding, is used to represent the spoken language with words conveyed through letters so that thoughts can be made permanent. Complete comprehension of the code requires both decoding (reading) and encoding (writing). With intense and sustained practice, individuals who do not have dyslexia become able to develop a high level of skill such that these processes become nearly automatic. Individuals with dyslexia who are learning to read the English Writing System struggle tremendously. Learning to read an alphabetically-based writing system specifically and emphatically requires attending to and learning about the smallest units of language.

Sophisticated eye movement technologies examining skilled adult readers have indicated as many as 15 - 25% of words are not initially fixated during reading [71]; thus words that are short, high-frequency, predictable and are acquired early in reading development are likely to be skipped and, therefore, not fixated. In addition, compared to adults, children are more likely to have more fixations (fixating on more words than adults), have fixations of longer duration, have shorter saccades, have more refixations (fixating on a word that was previously fixated), and make more regressions [72]. Eye movement studies only included children who were capable of reading simple sentences without the need for decoding [73]. For children beginning reading acquisition, attention to each letter in a word is necessary. The unit of analysis in terms of reading is the letter. It is the letter that holds the key to deciphering words into their sounds such that reading can take place.

As an example of the difficulties associated with utilizing a system that does not employ the Science of Reading, California in 1987 embraced the conceptual framework of WL. The school systems used WL textbooks and the phonics approach was largely deemphasized if not eliminated. By 1994, the fourthgrade reading scores from California were tied with Louisiana’s and Guam’s as the worst of the 39 states and territories that participated in the national standardized reading test (National Assessment of Educational Progress). As a result, legislative hearings occurred and a task force was commissioned. Granted, there were likely other ancillary reasons for the poor reading skills observed in 1994, but their combined reports determined that the WL approach was an inappropriate reading acquisition strategy.

Soon thereafter, the Australian Government in 2005 recommended systematic instruction of synthetic phonics and argued that WL, “on its own, is not in the best interest of children, particularly those experiencing reading difficulties." [74] and also reported that “direct systematic instruction in phonics during the early years of schooling is an essential foundation for teaching children to read" (p: 11).

The WL framework has been the persistent persuasive myth of our time. It sounds so organic and liberating. Simply expose children to good literature and to common words consistently and allow them to grow naturally into strong readers at their own pace and they will become competent readers. No need to first instruct children how the writing system actually works, that words need to be decoded before they can be read. Simply guess at the pronunciation of the word. Obviously, even to the individual who has no background in reading acquisition, this sounds ludicrous and it is. It is crucial that children engaged in reading acquisition have access to the meaning and purpose of the English writing system and that it represents a code. Reading acquisition is first and foremost a process of learning how to decipher printed words into their respective sounds and synthesizing those sounds once decoded to read words. The English Writing System was based on an alphabet, which acts as a Rosetta Stone so that individuals can transcribe sounds into symbols and directing the symbol representation of the sounds. It is crucial that children learning to read are taught the relationship between sounds and symbols, decoding and synthesizing.

Many children are able to comprehend the nature of the code and are able to appreciate that the English writing system is indeed a code to be used to decipher text. Once this notion has been comprehended, more advanced strategies can be deployed. Unfortunately, the child with dyslexia and many children who do not naturally divine the relationship between sounds and letters have grave difficulties learning to read. Most children require the code to be explicitly taught. Instructional strategies that initially assist beginning readers to understand the nature of the code and then build upon that foundational knowledge emphasizing comprehension and other strategies, become competent readers [75]. Failure to present this vital information results in a large number of children who experience reading failure. Colleges of education are complicit in this conspiracy and are negligent when they forsake to educate pre-service teachers in the Science of Reading. Failure to do so results in teachers who know very little about the specific nature of reading acquisition and who are unable to assist struggling readers. It is imperative that students who desire to be teachers have a strong knowledge base in the Science of Reading. The continued failure to adequately prepare future teachers with regard to the Science of Reading, reading acquisition, the nature of dyslexia, assessment and interventions will result in a continuation of reading acquisition failure. This is extremely unfortunate in that the knowledge, skills and technology exist so that reading failure can be prevented or attenuated.

It is clear that pre-service and seasoned teachers along with professors of education who teach these individuals have insufficient knowledge with regard to the Science of Reading; the underlying principles related to reading and it subcomponents that guide reading instruction, evaluation and intervention strategies. This is just not true with regard to reading acquisition in general, but training individuals with dyslexia to read. The root cause of this deficiency of knowledge rests squarely on colleges of education in two very important ways. The first involves the lack of appropriate training of individuals pursuing the educational doctorate and the second involves the lack of dissemination of the scientific literature to pre-service teachers by colleges of education faculty who lack exposure to science, research methods, design and analysis.

Higher Education’s Contribution to Reading Failure

Doctoral training

Shulman et al., [76] wrote that “the problems of the education doctorates [Ed.D. and Ph.D.] are chronic and crippling. The purposes of preparing scholars and practitioners are confused; as a result neither is done well.”. Purinton [77] argued that “Ed.D. programs—even highly ranked ones—have a long way to go in establishing their indispensable value; by far, such degrees have still not lived up to the standards set by other professional doctoral programs” (p: 25). The major deficiency with education doctorates is that they appear to lack the necessary training in research methods, design and analysis. Although these degrees often include coursework that include research methods, design and analysis, the incorporation of these courses into other content areas is lacking. “In education, the judgments of ‘experts’ frequently appear to be unconstrained and sometimes altogether unaffected by objective research. Many of these experts are so captivated by romantic ideas about learning or so blinded by ideology that they have closed their minds to the results of rigorous experiments. Until education becomes the kind of profession that reveres evidence, we should not be surprised to finds its experts dispensing unproven methods, endlessly flitting from one fad to another. The greatest victims of these fads are the very students who are most at risk.” [78]. As a results, it is critical that those pursuing education doctoral degrees have a very good working ability to engage in consuming research. There appears to be a serious lack of quality in educational research which [65] argued is directly related to weaknesses in doctoral preparation. In fact, the Carnegie Project on the Education Doctorate (CPED) was created to redesign the doctoral preparation to address the growing criticism regarding this lack of preparation. The CPED presently consists of 83 colleges and schools of education whose goal is to critically examine the doctorate in education. In particular, one of the initial goals was to differentiate the Ed.D., which was considered a practitioner doctorate preparing candidates to solve educational issues, from the Ph.D., which was considered a research-based doctorate that prepares candidates to be university faculty and educational scholars. Unfortunately, these two degrees fail to be differentiated in this manner. Frequently, neither degree provides the appropriate training in science for either of them to generate scientific knowledge that can be used to solve educational issues [79]. This is most certainly the case when reading acquisition failure is considered. Lastly, the curriculum often lacks practical relevance in relation to the educational issues that exist [80].

The second dimension of suggested pedagogy from the CPED is that “teaching and learning are grounded in theory, research, and in problems of practice.” [81]. There is no doubt that this should be the case, teaching and learning should unequivocally be grounded in research and theory; however, the status quo in far too many doctorate programs in education is that research is not seriously emphasized, taught or integrated into doctoral program course content. The redesign of doctoral training in education must be framed around a scientist-practitioner or scholarly-practitioner model in which the process and content of science are firmly established. Otherwise, the discipline is doomed to continue following unsubstantiated notions that do not allow practitioners to firmly understand educational realities. In fact, the CPED suggests that the “scholarly practitioner” model be used by colleges of education use to build or redesign Ed.D. degree programs. The scholarly practitioner should have a very firm grasp of the process and content of science including the scientific method, understand the importance of science in solving educational issues and should consult the scientific literature when addressing educational problems.

Doctoral programs in education, whether the program provides training for the Ed.D. or the Ph.D. degree, should provide candidates considerable background in science which would include research methods, design and analysis with emphasis placed on incorporating these concepts within each content area and course. Doctoral students should engage the primary source literature in each class and become very proficient in its content. Students in Ph.D. programs should also be required to develop a research proposal in each content area and course that is strongly based on the scientific literature relevant to the course. This not only helps the student understand the importance and necessity of becoming proficient in a literature, but also helps them to learn the craft of the literature review and the research enterprise. Students pursuing the Ed.D. should be provided coursework that strongly emphasizes the importance of science in solving educational issues. Students should always search for solutions to educational issues from the scientific literature. To be able to do so requires that the student have a firm grasp of how to read scientific material and its importance. After students have a basic understanding of science, research methods, design and analysis, all students must also be proficient in the Science of Reading. This cognate should be part of each doctorate in education program. Before reading failure can be adequately addressed, a common thread of knowledge must be present in all of the following personnel; superintendents, principals, reading specialists, teachers, school support personnel, and paraprofessionals. This knowledge is necessary so that all have a common language in which to converse and have a reasonable expectation of providing appropriate interventions. This conversation must be led by those engaged in doctoral training so that the doctoral candidate will graduate with the appropriate knowledge. Other cognate areas should be determined by the specialization that the program wishes to offer, but it should be nonnegotiable that all doctorate in education programs include a substantial core of knowledge that emphasizes the importance of science in the pursuit of educational knowledge, presents research methods, design and analysis as stand-alone courses in addition to infusing this content into each course. These science-based courses should be presented at the very beginning of the student’s course content and performance in these courses could act as a litmus test for continuing the degree. Additionally, the Science of Reading cognate must be part of each doctoral program. This is the only way that reading failure can be adequately addressed. Failure to provide essential knowledge in science and exposure to its literature continues to promulgate ignorance with regard to educational knowledge, which is particularly the case with regard to reading, reading acquisition and reading failure. Binks-Cantrell et al., [82] refer to this lack of knowledge as the Peter Effect [83] in which individuals cannot teach what they do not know themselves. There is no specialization area that would lead to a doctorate in education that could forgo the Science of Reading content. One might argue that this information is not pertinent to the doctor of education degree (e.g., curriculum and design, administration or leadership), but this is simply not accurate. Understanding the nature of reading acquisition and how to rectify acquisition failure is vitally important. This content must be firmly addressed in the curricula of both the Ed.D. or Ph.D. Failure to do otherwise continues the trend of failing to meet the needs of children with dyslexia, their families and society in general that requires that it citizens read and read well.

It is critically important that individuals who will become faculty members in colleges of education have the knowledge contained within the Science of Reading. The great failure has been the lack of training in the Science of Reading in colleges of education faculty members. The current state of affairs of the Science of Reading has provided considerable information regarding the acquisition of reading skills, particularly in children who have dyslexia and reading difficulties, the nature of evaluation and assessment, and science-based interventions and curricula. The abysmal performance of pre-service and in-service teachers and college of education faculty on the content of the Science of Reading trickles down to the students who are suffering due to the lack of training of all of these individuals. The Science of Reading needs to be requisite for both doctor of education degrees.

Given the vital importance of correcting the dilemma facing our nation’s colleges of education, public and private elementary and secondary schools with regard to reading failure, it is recommended that colleges of education only hire faculty who have been trained in the Science of Reading during their doctoral training. For those who have not, it is also recommended that colleges of education provide post-doctoral training in the Science of Reading. There will be those who argue that this is not necessary, but the fact that nearly 20% of our nation’s children have dyslexia and that 32% of fourth graders were reading at a level below Basic and 65% were reading at a level below proficient [84] are very strong counter arguments for this position. It is essential that colleges of education faculty have the requisite knowledge to dispense the science-based and appropriate knowledge to teach reading to pre-service teachers. Failure to do so will only prolong the inability of students to acquire proficient reading skills. As articulated by Louisa Moats, “Everyday I’m in a school and working with teachers I continue to be astounded by the gulf of knowledge, the gulf between our knowledge base in the scientific community and the practices that go on in teacher training” [85].

Graduate training

The same arguments as articulated above should also apply to any graduate training in education, be it the master’s in education degree or the educational specialist degree (Ed.S.). It is critically important that these degrees have content with regard to science, research methods, design, statistics, and the nature of dyslexia and reading failure which should include coverage of etiology (genetic and neurological), characteristics related to children who experience dyslexia and reading failure, characteristics of dyslexia, evaluation tools, and science-based interventions and curricula with practicum experience based on the content concerning the Science of Reading. A graduate degree in reading absolutely must comprehensively and specifically cover these content areas.

Undergraduate training

At the undergraduate level, many teacher education programs do not provide adequate training for pre-service teachers [59,86,87]. As mentioned above, pre-service teachers perform poorly on their knowledge of the Science of Reading. Reorganizing and restructuring colleges of education courses to include the Science of Reading is necessary. A core curriculum for pre-service teachers should include coursework covering reading psychology and development, the structure of language, applying best practices in reading instruction and using validated, reliable and efficient assessments to inform classroom instruction [44]. Unfortunately, only a very small number of colleges of education include such coursework. This led [58] to develop a strategy where colleges of education could be rated on their ability to provide instruction. An alarmingly great many of the colleges of education provided minimal to no training in the Science of Reading. This is certainly disappointing as research has determined interventions that are successful in improving reading skills of students experiencing reading failure [88]. The vast majority (78%) of elementary education programs were found to have curricula that did not “adequately address strategies for struggling readers” [58] for Standard 4: Struggling Readers. The authors indicated that the criterion used to determine if a program met this standard was quite low. Even so, nearly 80% of the programs failed to meet this standard.

What specifically should be taught?

Pre-service teachers must be provided with a curriculum that includes the Science or Reading. The Science of Reading corpus includes the nature of reading, how reading should be taught, evaluation tools for determining appropriate progress in reading and interventions that are useful to assist struggling readings to become competent readers. However, prior to students’ exposure to the Science of Reading, they must also have exposure to prerequisite courses that would allow them understand the mechanics of the Science of Reading.

A very useful guide in developing the curriculum for pre-service teachers can be found in the Knowledge and Practice Standards for Teachers of Reading that was developed by the International Dyslexia Association (Tables 1 and 2). The Knowledge and Practice Standards for Teachers of Reading includes essential knowledge (Section I) in addition to standards concerning demonstrating the knowledge and skills that teachers should have to provide services to students with dyslexia or reading difficulties (Section II). The standards in Section I comprise oral and written learning, knowledge of the structure of language, phonology, phonics and word recognition, fluency, vocabulary, comprehension, handwriting, spelling, written expression, assessment for planning instruction, and knowledge of dyslexia and other learning disorders. The standards in Section II concern the demonstration that the teacher is competent to teach reading (Level I) and for specialists who intend to provide services to individuals with dyslexia and other learning disorders.

| Section 1 Knowledge and Practice Standards | |

|---|---|

| Areas | Examples |

| Foundation Concepts about Oral and Written Learning | This section outlines the standards regarding the knowledge and application related to the influence that oral and written language contributes to reading and writing, cognition and behavior that affect reading and writing, environmental, cultural and social factors, typical development, causal relationships of the above, and reasonable goals and expectations for learning. Phonological, orthographic, semantic syntactic and discourse processing; attention, executive function, memory, processing speed, graphomotor control; development of oral language, phonological skill, printed word recognition, spelling, reading fluency, reading comprehension, written expression. |

| Knowledge of the Structure of Language | This section outlines the standards that refer to the individuals teaching reading should have regarding the structure of language with regard to phonetically regular and irregular words, common morphemes and sentence structure. Phonology (concepts regarding vowels and consonants), orthography (graphemes, high frequency and irregular words, orthographic rules, syllable types), morphology (common morphemes in the English Writing System), semantics (semantic organization), syntax (distinguish phrases, dependent and independent clauses in sentences, parts of speech) and discourse organization (narrative and expository discourse, construct expository paragraphs, identify cohesive devices in text). |

| Structured Language Teaching: Phonology | This section outlines the standards that refer to teaching phonology. Underdeveloped phonological processing has been identified as a core weakness in individuals who have dyslexia. Teaching phonological processing skills is a very important component in remediating poor reading skills. Identify goals of phonological skill instruction, know the progression of phonological skill development (rhymes, syllables, onset-rimes, phonemes), principles of phonological skill instruction (brief, multisensory, conceptual and auditory-verbal), understand the reciprocal nature of phonological processing, reading, spelling and vocabulary, and understand how the phonological features of a second language might interfere with English pronunciation and phonics. |

| Structured Language Teaching: Phonics and Word Recognition | This section outlines the standards that refer to teaching systematic phonics and accurate word decoding skills. Recognize how to order phonics concepts, understand explicit and direct teaching, understand multisensory and multimodal techniques, understand lesson format from word recognition to fluent application in meaningful reading and writing, understand research-based adaptations of instruction for students who have weaknesses in working memory, attention, executive functioning or processing speed and the application of the above concepts. |

| Structured Language Teaching: Fluent, Automatic Reading of Text | This section outline the standards that refer to teaching fluency. Underdeveloped or poor fluency is a characteristic of dyslexia and inhibits other reading processing including comprehension. Understand the role of fluency in reading, that fluency is a stage of normal reading development occurs with practice and may be a symptom of some reading disorders, understand the concepts of frustration, instructional and independent reading levels, what instructional activities are likely to improve fluency, techniques that will assist in reading motivation, and understand the appropriate use of assistive technology and the application of these concepts. |

| Structured Language Teaching: Vocabulary | This section outlines the standards that refer to vocabulary and its importance with regard to reading comprehension in addition to providing teachers information with regard to the importance of vocabulary in reading and listening and how to provide a classroom environment that is rich in access to vocabulary. Understand the role of vocabulary development and knowledge in comprehension, understand the role of direct and indirect methods of vocabulary instruction, know the techniques used to teach vocabulary before, during and after reading, understand the reasons for the considerable variability in students’ vocabularies, and teaching word meaning. |

| Structured Language Teaching: Text Comprehension | This section outlines the standards that refer to reading comprehension, particularly teaching comprehension and identifying weaknesses that require intervention. Be familiar with teaching strategies that are appropriate before, during and after reading, contrast the characteristics of major text genres including narration, exposition and argumentation, understand the relationship between text comprehension and written composition, identify potential miscomprehension in text, understand the levels of comprehension including surface code, text base and mental model/situation model, understand factors that contribute to deep comprehension. |

| Structured Language Teaching: Handwriting, Spelling and Written Expression | This section outlines the standards that refer to handwriting, keyboarding, spelling and written expression including capitalization and spelling. Know research-based principles for teaching letter naming and letter formation, techniques for teaching handwriting fluency, recognize and explain the relationship between transcription skills and written expression, identify students’ levels of spelling development and orthographic knowledge, be able to explain the influences of phonological, orthographic and morphemic knowledge on spelling, understand the major components and processes of written expression and their interactions, know grade and developmental expectations for students’ writing and understand appropriate uses of assistive technology in written expression. |

| Interpretation and Administration of Assessments for Planning Instruction | This section outlines the standards that refer to interpreting and administering assessments for planning instruction. This section includes standards that must be demonstrated for not only the content knowledge and its application, but also competencies for teaching students with dyslexia and related difficulties. Understand the differences between screening, diagnostic, outcome and progress-monitoring assessments, the basic principles of test construction, including reliability, validity and norm-referencing and know the most well-validated screening tests, understand the principles of progress-monitoring and the use of graphs to demonstrate progress, know the range of skills typically assessed by diagnostic surveys of phonological, decoding, oral reading, spelling and writing skills, recognize the content and purposes of the most common diagnostic tests used by psychologists and educational evaluators, interpret measures of reading comprehension and written expression. |

| Knowledge of Dyslexia and Other Learning Disorders | This section outlines the standards that refer to understanding the nature of dyslexia and other learning disorders. Understand the most common intrinsic differences between good and poor readers, the tents of the NICHD/IDA definition of dyslexia, that dyslexia and other reading difficulties exist on a continuum of severity, be able to identify the distinguishing characteristics of dyslexia and related reading and learning disabilities, identify how symptoms of reading difficulty may change over time in response to development and instruction, and understand federal and state laws that pertain to learning disabilities, especially reading disabilities and dyslexia. |

Table 1: Section 1 of the knowledge and practice standards for teachers of reading.

| Section 2: Guidelines pertaining to Supervised Practice of Teachers Who Work in School Settings | |

|---|---|

| Level | Description and Requirements |

| I | Description: This level is intended for novice teachers in training who implement an appropriate program with fidelity, formulate and implement an appropriate differentiated lesion plan, and demonstrate proficiency to instruct individuals with reading disability or dyslexia. Requirements:

|

| II | Description: This level is intended for specialists who must demonstrate additional expertise and abilities to provide services to individuals with dyslexia and other learning disorders. Requirements:

|

Table 2: Section 2 of the knowledge and practice standards for teachers of reading.

It is recommended that pre-service teachers fulfill prerequisite courses before exposure to the content of the Knowledge and Practice Standards. These prerequisites would be comprised of research methods, linguistics, cognition and a course outlining the Science of Reading. Section II of the Knowledge and Practice Standards lists practicum experiences that are recommended. If the Knowledge and Practice Standards are not used as a guide for developing the sequence of courses, then two different practicum experiences should be included (Table 3). The rationale for the prerequisite courses concerns providing the appropriate background knowledge so that pre-service teachers could benefit from the courses designed from the Knowledge and Practice Standards. The course would be an overview of the technical aspects of the scientific method, design, analysis and how scientific results are communicated. It is important that preservice teachers are provided with a framework to comprehend not only the knowledge contained within the Science of Reading, but to appreciate the procedures in which data are collected and analyzed. The suitability of pre-service teachers to engage in teaching reading will be determined by their understanding of the methods by which data are generated to answer specific questions that lead to practical applications. The course in linguistics will include phonology, phonetics, morphology, syntax, semantics and grammar so that the pre-service teacher will have specific knowledge regarding language. Having a working knowledge of language and it subparts is critical to understanding reading acquisition. The last prerequisite course should include content in cognition as much of the Science of Reading content was developed from cognitive science. As a result, a familiarity with the concepts, strategies and theories in this domain will prove to be essential. The content of this course should include attention, memory, perception, language and metacognition. These three prerequisite courses should provide a working knowledge of the content that will prepare them for understanding the content within the Science of Reading courses. Other potential prerequisite courses could also include an introduction to human neuropsychology, memory, sensation and perception, and additional coursework in research methods.

| Course Title | Course Content |

|---|---|

| Research Methods | Basics of scientific principles |

| Linguistics/Psycholinguistics | Introduction to linguistics |

| Cognition | Introduction to cognitive sciences which would include empirical methods, models, and data |

| Science of Reading | See Table 4 |

| Science-based Reading Evaluation and Interventions | Theoretical basis of assessment instruments and their results in addition to developing individualized interventions based on assessment protocols |

| Practicum in Reading I | Evaluation of reading and comprehension utilizing phonological processing, phonics, fluency and vocabulary. Develop strategies to assist in the development of reading acquisition |

| Practicum in Reading II | Evaluation of reading and comprehension in struggling readers utilizing phonological processing, phonics, fluency and vocabulary. Develop strategies to assist in the development of reading acquisition |

Table 3: Potential required courses to be included in an elementary education program to promote the science of reading.

The Science of Reading material could be offered as a single course or a series of courses; the material is voluminous (Table 4). There is enough content that several courses could be offered to outline the specific details. Other topics could be included as well. It is essential those pre-service teachers are not only familiar with the content, but can apply it. The two practicum courses would be designed to address the application of the material learned in the Science of Reading course or courses, the first of which would involve assessment and evidence-based strategies to assist with reading acquisition while the second practicum course would involve assessment and intervention strategies specifically for struggling readers. The instructor would observe and evaluate each student’s technique providing feedback during and after the process. The series of courses outlined above would provide preservice teachers the knowledge and skills necessary for them to appropriately teach reading to their students, it would also provide them with the ability to identify children at risk for reading failure and to provide the necessary intervention. Pre-service teachers desperately want this information as they want to be the bestpossible educators possible. Those who believed that their preservice preparation was less than satisfactory were more likely to leave teaching [89]. There is also evidence that teacher turnover harms student achievement [90]. Teacher preparation programs must provide pre-service teachers with all of the knowledge and skills that will be needed to provide quality education to their students. Those who are ill-prepared to begin their teaching careers are likely to harm their students’ academic achievement by first not knowing the appropriate reading acquisition and remediation strategies to provide to their students and then by leaving their profession. Students who struggle to learn to read are more likely to drop out of school. An enormous amount of human potential is not being realized due to the weaknesses throughout the educational process beginning with lack of rigor with regard to the Science of Reading during doctoral training which trickles down to pre-service teachers, reading specialists and masters-level educators. Colleges of education are behooved to develop the recommendations listed above.

| Course Content |

|---|

| Writing Systems Alphabetically-Based Writing Systems History of English Writing System Orthography Languages that contributed to the English Writing System |

| History of Teaching Reading 1880 to present |

| Mechanics of English Writing System Letter-Sound Correspondence Phonics |

| Visual Processing and Reading |

| Phonology and Phonological Processing |

| Lexical Access |

| Fluency |

| Morphemes and Syllable Structure |

| Interdependence of Phonological Processing, Fluency, and Vocabulary |

| Comprehension |

| Literacy |

| Assessment of Dyslexia and Reading Difficulties |

| Interventions for Dyslexia and Reading Difficulties |

| The Role of Attention in Reading Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder Appropriate assessment |

| Potential interventions The Effect of ADHD on Reading |

Table 4: Potential content for a science of reading course designed for undergraduate pre-service teachers.

Continuing education strategies

It is recommended that colleges of education develop continuing education strategies for in-service teachers to be exposed to the Science of Reading. This can be in the form of a potential master’s degree in which the major focus is on the Science of Reading, or courses and activities to mirror what was recommended above with the training sequence of pre-service teachers. Success has occurred in professional development strategies to assist in-service teachers understand various aspects of the Science of Reading [91]. If in-service teachers are provided with the appropriate content in professional development opportunities, they can become proficient in their knowledge of the Science of Reading [92] outlines the issues with regard to professional development and the variables that must be addressed for positive change to occur. It was also found that when university instructors were provided with professional development, their knowledge of the Science of Reading significantly improved as well as their pre-service teachers who they were teaching [93].

An example

The 79th Texas Legislature enacted House Bill 1, the “Advancement of College Readiness in Curriculum.” The goal of Section 28.008 of the Texas Education Code was to increase the number of high school graduates who were ready to begin college or careers. In the bill, the Texas legislature required the Texas Higher Education Coordinating Board (THECB), which oversees post-secondary education in Texas, and the Texas Education Agency (TEA), which oversees public education, to determine how they could act together to prepare students for post-secondary education. The act also required the THECB and the TEA to create Vertical Teams, which were comprised of faculty from secondary and post-secondary institutions and was the organization that developed the College and Career Readiness Standards (CCRS). The THECB established the Texas Faculty Collaboratives Initiative so that faculty who were preparing pre-service teachers would have access to current information regarding the CCRS so that they could train pre-service teachers which, in turn, would allow pre-service teachers to more effectively prepare their students to become college and career ready.

The Texas Higher Education Collaborative (HEC) was created in 2000 to ensure that scientifically based reading research (SBRR) and scientifically based reading instruction (SBRI) were contained within pre-service teacher education programs, alternative certification programs, and community teacher preparation classes. The objectives of the HEC are to support the Reading First Initiative by insuring that college of education faculty present SBRI to pre-service teachers, assist college of education faculty to incorporate SBRR materials into their courses, establish a collaborative so that college of education faculty who prepare pre-service teachers could support each other, to address Reading First Initiatives and to provide professional development for elementary and special education teachers to insure appropriate reading achievement of students. The HEC provides opportunities for teacher preparation faculty from colleges, universities, community colleges and alternative certification programs to communicate and discuss issues related to reading in addition to providing informational materials. HEC also provides an online collaborative; HEC Online. Interestingly, the HEC encourages educational administrators to act as literacy leaders. HEC also supports and encourages Educational Leadership and Educational Administrator faculty to embed SBRR into their courses as well. The major focus is not only to ensure that SBRR is integrated in courses so that pre-service teachers learn about the Science of Reading, but also ensuring that all higher education faculty are proficient in the Science of Reading and that they are disseminating that information to all of their students regardless of degree or program.

HEC provides seminars, assists in revising syllabi and course requirements to reflect SBRR, participates in site visits to ensure implementation of SBRR, provides online discussion groups, examines implementation of HEC initiatives with faculty and pre-service teacher surveys and examines pre-service teachers’ knowledge through surveys. Results of the HEC initiatives have indicated that higher-education faculty found participating in HEC activities to be highly beneficial. Not surprisingly, preservice teachers were more knowledgeable with regard to the Science or Reading [94]. The success of the HEC initiatives are due to legislative action that compelled change to occur, strong and collaborative leadership in developing programs, secondary and post-secondary faculty collaborating to develop appropriate standards, providing the support for higher-education faculty, many of whom had little to no knowledge with regard to the Science of Reading, the opportunity to learn, to change their thinking and to change course content. The satisfaction of highereducation faculty in the support and materials that were gained from HEC led to changes in course content which then led to increased knowledge of the Science of Reading in pre-service teachers.

The Texas experience is a model for other states and indicates that it is possible to provide the types of change outlined above. An enormously important component that contributed to the success of Texas’ initiative was that the knowledge and skills of research scientists were utilized in presenting at conferences and seminars hosted by HEC, many of whom are cited above. The content was driven by the Science of Reading (SBRR and SBRI), which is essential. Other states that attempt to create such an initiate, should model their programs very carefully to Texas’ HEC. Imperative in this approach is to have a legislature that is appropriately informed regarding the necessity of the inclusion of the Science of Reading including SBRR and SBRI. There will be resistant as has been documented thoroughly above, and the typical legislator will need to be educated on the importance of the Science of Reading rather than be persuaded by those who fear and resist change. Developing a goal with regard to reading success and then assisting faculty in and outside of colleges of education to participate in the creation of programs to address embedding the Science of Reading into courses for pre-service teachers is also important. The main focus should be on the students, particularly struggling readers, all of whom are dependent on colleges of education to create appropriate coursework so that pre-service teacher can become in-service teachers competent in their ability to teach all students to read.

Conclusions

Approximately 20% of our nation’s students are experiencing reading difficulties and the percentage of fourth-grade students who are reading below Basic and Proficient (33% and 58%, respectively) has not appreciably changed since 1992. Fortunately, there is a solution. First and foremost the history of ignorance, resistance and complacency needs to be exposed. Secondly, there is a scientific literature that prescribes how to improve reading abilities in young students. The solution involves providing pre-service teachers with the knowledge that will assist them to provide their students, particularly struggling readers, the types of assessment and interventions that will lead to improved reading skills. Reading courses must be developed or revamped to include the Science of Reading. In addition, pre-service teachers must be provided with the appropriate coursework such that they will be able to understand the mechanics of the Science of Reading prior to their exposure to that information. There really is no reason that individuals with dyslexia cannot become competent readers.

For there to ever be gained and sustained any social progress regardless of the ultimate ideal; for as Chomsky observes, social revolutionary change is gradual and incremental, building upon previous gains; the population must be better educated. At minimal, people must be able to read both in print and online.

One of the primary goals of social progress has always been mass education. Education begins with reading, and learning to read begins with a proper understanding and application of the Science of Reading. Children not only need not resign themselves to perpetual literacy difficulty and only partaking in a limited envisioned future. There exists in the immediate present a corpus of knowledge represented in the Science of Reading that is being stifled and opposed by the uninformed, educational social structures and educational power elite. It is necessary that a revolution begin such that the Science of Reading is presented in colleges of education so that pre-service teachers can become competent to teach reading to all of their students. This is, in fact, what pre-service teachers actually desire and should demand; to become the most competent teachers possible. The most promising way to ensure that students with dyslexia and those who are experiencing reading failure can become competent readers is expose the current tragedy of ignorance, complacency and resistance on the part of faculty within many colleges of education. It will be necessary to build stronger doctoral degrees in education with an emphasis on science, research methods, design and analysis along with substantial content within the Science of Reading. These faculty will then be competent to teach pre-service teachers reading acquisition strategies so that children will learn to read, even those with dyslexia and potential reading difficulties. “A society cannot afford to continue funding teacher training institutions whose educational philosophy promotes a bankrupt theory and its associated pedagogy in the name of social justice (or ‘inquiry’) in order to disguise their own intellectual bankruptcy. Alternatives to dysfunctional institutions must be created. A civically healthy society needs a system for teacher preparation that respects and honors rational approaches to issues in curriculum and instruction” [95]. The ability to create strong colleges of education whose mission involves utilizing science to solve educational issues and to disseminate the continued and growing knowledge contained within the Science of Reading is essential. Children with dyslexia and reading difficulties will continue to suffer until this is accomplished.

References

- Gallman RE, Weiss TJ (1969)The service industries in the nineteenth century. In: Ruchs VR, Production and productivity in the service industries, New York: Columbia University Press, pp: 287-352.

- Kendrick JW (1961) Productivity trends in the United States. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Bureau of Economic Analysis-US Department of Commerce, National Income and product accounts.

- Conkin Paul (2008) Revolution Down on the Farm: The Transformation of American Agriculture since 1929 (1stedn.) University Press of Kentucky.

- U.S. Census Bureau (1990) U.S. Census.

- U.S. Census Bureau (2013) American Community Survey.

- Cox KE, Guthrie JT (2001) Motivational and cognitive contributions to students'amount of reading. ContempEducPsychol 26: 116-131.

- Shaywitz SE (2003) Overcoming dyslexia: A new and complete science-based program forreading problems at any level. Knopf.

- Tallal P, Miller SL,Bedi G,Byma G, Wang X, et al. (1996)Language Comprehension in Language-Learning Impaired Children Improved with Acoustically Modified Speech. Science 5: 81-84.

- Terras MM, Thompson LC, Minnis H (2009) Dyslexia and psycho-social functioning: in exploratory study of the role of self-esteem and understanding. Dyslexia 15: 304-327.

- Alexander-Passe N (2016) Investigating Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) Triggered by the Experience of Dyslexia in Mainstream School Education. J PsycholPsychother 5: 215

- Alexander-Passe N (2016) Dyslexia: Investigating Self-Harm and Suicidal Thoughts/Attempts as a Coping Strategy. J PsycholPsychother 5: 224.

- Fuller-Thomson E, Hooper SR, Kennedy M (2014) One third of adults with dyslexia report they were physically abused during their childhood. University of Toronto 30.

- Cortiella C, Horowitz SH (2014)The state of learning disabilities: Facts, trends and emerging issues. New York: National Center for Learning Disabilities.

- Literacy Development for Juvenile Offenders: A Project of Hope (2003)National Criminal Justice Reference Service,pp: 1-7.

- Hurford DP, Fender AC, Swigart CC, Hurford TE, Hoover BB, et al. (2016) Pre-service teachers are competent in phonological processing skills: How to teach the science of reading. Read Psychol 37: 885.

- Aslin RN, Newport EL (2012) Statistical learning from acquiring specific items to forming general rules. CurrDirPsycholSci 21: 170-176.

- Oller DK, Wieman LA, Doyle WJ, Ross C (1976) Infant babbling and speech. J Child Lang 3: 1-11.